The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoraled. Joshua Corey and G. C. Waldrep

Ahsahta Press, 2012

The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoraled. Joshua Corey and G. C. Waldrep

Ahsahta Press, 2012

review by Hannah Ensor

Well, it’s the 21st century. And, as Joshua Corey points out in his introduction to The Arcadia Project, even the weather—“the tentative ambient glue between persons otherwise unlike”—is politicalized; wrought; unsafe. So what do we do? What do we write?

The pastoral may not be your first thought. Even its simplest definitions include the genre’s very constructedness; the way it smacks of escapism, evasion, of the harder realities of our world; a pastoral is, according to my Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, “a fictionalized imitation of rural life, usually the life of an imaginary Golden Age, … To insist on a realistic presentation of actual shepherd life would exclude the greater part of the works that are called pastoral. Only when poetry ceases to imitate actual rural life does it become distinctly pastoral.” And we’re so over escapism… right? At least as poets/reader-consumers1 of poetry? If the pastoral isn’t right, what about the unexpected portmanteau of “pastoral” and “postmodern”?

This anthology—and the more-than-five-hundred pages of what it terms “postmodern pastoral” poems—is definitely positioned differently than its Arcadian predecessors. Whereas the pastoral poem or painting of yore may be positioned gazing from a real world of difficulty toward an escapist fictional world of delight and safe pleasures (ah, to picnic nude in the countryside!), the pastoral of today comes from our seemingly delightful and safe world—the one of immediately- and overwhelmingly-gratifying spectacles; of the precious self-righteousness of green tote bags; of going for real picnics in a pristine-enough-to-satisfy-us countryside wearing our rugged performance outerwear2—toward an attentive experience of our lived realities.

Given that in 2013 “[w]e are [actually] living in Arcadia: that bubble riding atop the tidal forces of history” (this from Corey’s wonderful introduction), our pastoral poetry today must invert and contort: the escapist reality is, surprisingly, one in which we manage to attend to the world as we are actually inhabiting it. If the pastoral of yore was about escape instead of engagement, the postmodern pastoral is about escaping to a world of engagement.

This is radical and needed and terrifying and—whoa, who would’ve thought?—a hell of a lot of fun.3 By which I think I mean: stimulating, and startling, and diverse enough to take up almost 550 pages with spinning, vivid, yelling, moaning, laughing, observant poems.

Again, from Corey’s introduction: “The contemporary versions of pastoral presented in this anthology … [combat] cynicism, apathy, and despair with their fierce commitment to the intersections of the present tense with the boundaries of historical and ecological knowledge.” He continues: “this book is a call to imagination—not to the imagination of dire futures, but to the interruptions of poetry.”

Why the pastoral? Why poetry at all? Why an anthology? “If it is to be not altogether delusional and vain, an anthology such as this one must be a living and motile assemblage of our best hopes for what poems can be: vessels of attention to the world and to language, attention at its most intense. To be present, with/in the world, with/in words, in active relation to the living (and dying) environment—that is the ordinary utopianism practiced by these extraordinary poems.”

Sold yet?

---

I’ve mentioned that this anthology is more than five hundred pages long, right? It’s incredible. There are one hundred four contributors, but what’s more remarkable is that the length of contributions ranges from one page to twenty-one. Many of the poems (including excerpts from longer projects) are short, spanning a couple of pages then moving to the next. But perhaps the most notable part of this anthology’s sheer length is that it allows room to print longer pieces: poems that require time to breathe, time for the reader to adjust to them, time to unfold and expand and contort back upon themselves and shift and warp. I was consistently swayed, even won over, by the longer poems printed in The Arcadia Project, even poems I began on the outside of. Indeed, looking back on my underlinings and embarrassingly-emphatic marginalia, many of them start on page three or four of these longer pieces: just around when I started, in retrospect, to acclimate to a voice, or to a set of ideas or logics that the poem spun out.

If you’re thinking: “Twenty-one pages? That’s a damn chapbook!” Well, yes, it could be. And thank goodness that the whole thing’s in there. Brian Teare’s twenty-one page “Transcendental Grammar Crown” uses as much white space as it needs; is a field, an exhalation. No “3-5 pages per poet” rule squeezed the poems/poets into crevices, pressurized what didn’t want to be pressurized. Instead: twenty-one pages, for instance, with Teare’s spaced-out, spread-out, voice that wants to immerse us, and can, and does. Doesn’t it sometimes take that long to get inside of someone’s language? To, once inside, stay inside? Be in it?

There are more than twenty contributions that span seven or more pages. We get a dystopian-corporo-feminist world built by Catherine Wagner; a careful and incisive and growing set of notes on our minds and birds and forests and how we write by Brent Cunningham; a warping, weaving, spinning, confusing, jumpy, entertaining pseudo-fairy tale from John Beer that leaps away and away; a sixteen-page post-Thoreauvian berrying poem from Stephen Collis that points astutely to the reality that—just as Thoreau’s own huckleberry-picking was never apolitical—even a 21st century experience of picking blackberries can be both pleasure/community and a “palimpsest” of cultural/social/environmental complexities.

And then there’s Rusty Morrison’s contribution, which adds up to nine pages. Nine is not, by a long shot, the most in the anthology. But what’s notable here is how close to a mini-collection we get from her. First, we read “Field Notes: 1-6” (already a collection of its own, philosophical and observant, clipped/reduced and full), then we shift gears into “Making Space,” a poem in sections itself, all of which together is, relatively speaking, dense, perhaps even vaguely narrative (if not narrative, populated), while following many of the same syntactical reductions of “Field Notes: 1-6” and adding new tricks to the arsenal (small caps assertions/slogans/philosophical statements juxtaposed against the more personal, gentler poem-surrounds). Then, seven pages after we first encountered “Field Notes,” we return: “Field Notes: 13-16.”

Morrison’s “Field Notes: 1-6” starts with an epigraph from Gilles Deleuze: “[A] sum but not a whole, Nature is not attributive, but rather conjunctive: it expresses itself through ‘and’ …”

What a gift that Ahsahta has given to Corey and Waldrep; what a gift they have passed on to their contributors and to us the readers: space and permission to let poems take a little bit of time. Anthologies are all-too-often “samplers,” zipping from voice to voice like a TV clip show. The Arcadia Project is a stack of chapbooks with pages dog-eared by some friend you really trust to show you something good and important and good some more.

My Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics sits open to its entry on “Pastoral.” Closed, the encyclopedia is just barely taller than The Arcadia Project. They sit alongside each other nicely, and I’m sure I’ll have both nearby for years to come.

---

Though I started by talking about Corey’s introduction, I should note that this anthology is not a book of criticism, and is not interested in foregrounding its own editorial framing. As I’ve mentioned, the anthology spans about 550 pages, with very spare front-/middle-/back-matter. Besides the brief introduction Corey offers, the editorial input is quiet: Corey and Waldrep have made their presence known only in the cogent organization and (unannotated, unexplained) section-headers.

And while the book-geek part of me was at first disappointed to not have more bookish infrastructure, framing, prefatory notes and critical introductions to each section (defining for me what a “New Transcendentalism” might be, what to think when I hear “Necro/Pastoral”4), ultimately it’s the poems that tell this story, and tell all of it, the story that pushes against itself and hews its own poetic field and growls and burns.

When I think of the part of me that was disappointed to not have it all laid out for me, explained (away?) before reading a single poem therein, I think of Dorothea Lasky’s Poetry is not a Project. It’s a question that’s gotten, I hope, its due when it comes to single-authored poetry books, but is maybe a question we could stand to ask more in this context: what makes an anthology foreground its poems over its project? What of the risk that the title, the introduction, or the back cover, could stand in for the hopefully thriving, bustling, self-contradictory and complex content? The Arcadia Project does this. Juxtapositions between poems speak loudly; sections are, it seems, framed by “first” and “last” poems that interact to draw an arc; poems within share some of the same heavy lifting and work against each other. Corey and Waldrep don’t “come down on the side of” this or that; prioritizing poets or ideas. The poems compel or they don’t; they speak for the book or they don’t.

Of course, the critical contributions are also out there. The explanations. The discourse around the “postmodern poem,” and its interactions with the “pastoral.” In fact, you don’t even have to look too far away from The Arcadia Project: just go to the website for the anthology. The site includes essays by Corey that he didn’t include in the book. Outside references. Teachers’ guides and discussion questions. It goes on. It expands. Don’t we all know this already? That the book in the 21st century doesn’t stop at its covers?

---

The Arcadia Project is an admirable experiment in/expression of where 100-plus decidedly 21st century poets stand on “nature poetry”: what it is, what it addresses, how it approaches and backs away and turns and approaches, how Nike and Twitter and Hammermill Papers share space with stalagmites and raincoats; share space with blood and birds and trees and hills and ravines. This anthology can—and should, in my estimation—take its place on environmental literature syllabi for the next twenty to a million years.

So yes, come to The Arcadia Project with an eye towards where poets stand on the nature poem. But come, too, to see how these poems are decidedly 21st century poems; to see what this anthology (its poets, its editors, the press) has to say about what a poem is.

Through this lens of what Corey and Waldrep did include, selected for, the lens of what moment we’re in now, I’m excited to see as much work with sound—with punning, eye-rhyme, rhyme-rhyme, assonance, consonance, alliteration—as there is. So many of these poets slip between words, make their connections with words-as-material and also between what these aural-oral consonances act like, reflect, do, more broadly. The slipping, maybe, of the 21st century: distraction, yes; piled-on denotations; suddenly finding yourself in a new place, seemingly unconnected by content-based logics but wholly connected by other tissue. Maybe it’s by what’s playing on the TV or by what the commercial environmental rhetoricians/ad-men are spewing at the moment, or, not-so-simply, by sonic logics as in Jane Sprague’s “Politics of the Unread” taking us through ideas overlapping syllable-by-syllable:

flipped gaze the mimic

to stutter arctic—or just tic

a long thigh a long thick

finger of grease

spill leak from something

these monstrous yachts

doth offend thee oh evermore

than any Ulsan oil seep

gutter to stillness

or smother the grunions

left offspring

eke out a living

Or we find play with the words cervix & server, watch as they become “servix” and “cerver,” watch as play with corporate behemoth Procter & Gamble transform them into figures, characters, representatives of their denotative categories (a proctor of a test; a gambler) in Catherine Wagner’s refiguration / theatrical proscenium / playful dystopian narrative (or as she calls it, “A Romance”).

Look at how this Michael Dumanis poem starts:

I thought there was a war on. I was wrong. To think the war

was over me! The war was over. No: the war was over

there, the other side of the barbed wire enclosure

from our side, warless, …

and later in the same poem, sound takes over more fully, its own logic leading the way: “go, go, Giselle / through Gaza’s gossamer,” then, “Giselle, disguised, / find something in your glossary / of gazes to assuage / each gasp in Gaza / each gasp is a palette of grays.”

Maybe it’s naïve to call use of sound “brave,” but I feel that it is. Are we ready to be less embarrassed about our aural draws to language? to rhyme when we want to rhyme, to pun when a pun is what’s called for? to inhabit the sounds and slippery logics of aphorism? Are we ready to use all of the tools language affords us? All its tricks and draws? This anthology suggests: yes, let’s do it already.

Indeed, one section of The Arcadia Project is called “Textual Ecologies” (I’ll reveal my hand enough to say that this was, in my estimation, one of the most thriving sections as a whole). The online teacher’s guide describes the section aptly as “work that views language itself as “landscape,” or as a natural and naturalizing extension of landscape.” Yes! Using sound and beyond sound, these pages are each their own field. They occupy space and use it and we’re suddenly inside of a created place.

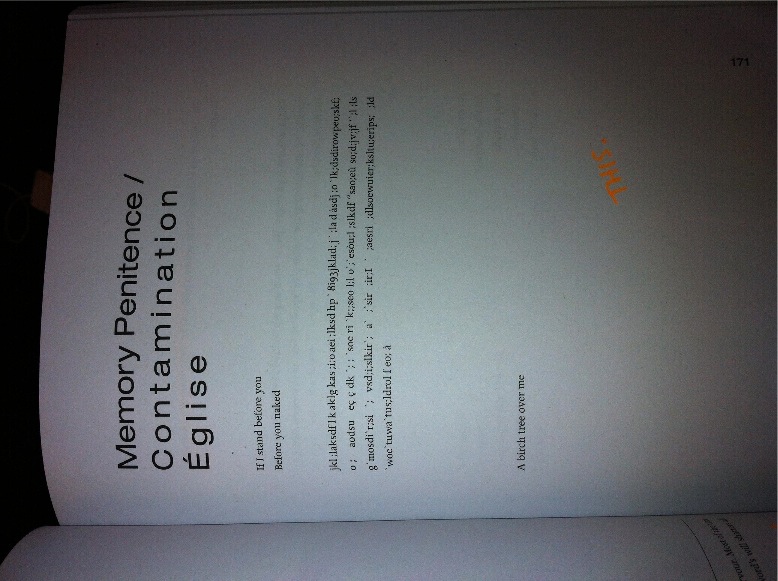

Look at this page. I took a picture of it with my iPhone. It’s by Erín Moure.

As is the case on this first page, the poem continues on in oscillations between sections that are readable as “poem,” sections that read as “not-poem.” One section joins words with the kind of typing-garbage (I say with awe) we saw on the first page:

Readability a context raises leaf a clear holographiea impediment holyoke, a crie donc amiable etruscan hole emmedial ,imtrespt , obligate , perflux creede lff;wejk fea tueauoriu`l a ‘lfk èaoeiur op;ajdvkrleu; `tjl`lsd l`àf` ;oertl l a;le er`f;dla`flk ae-wopr `pa`fò;e oad``;o;w`lkat;li`eo``àwp:i;eo`f e àsd f;l aeoi ; òo `;;soe to9ow l```lw-pooeri

At what point do we start failing to track these as “words”? Is it when the syntax breaks down? Is it at the first “unrecognizable” word (though even then we might question: is it I who doesn’t recognize this English-language word, or is it that it’s invented/misspelled/not a word at all)? Is it when the words “sound” as words but don’t quite “mean” as words? And what about the accented letters/characters? This isn’t the product of throwing the hands down on the keyboard (each à on my computer takes three keystrokes). Does that change anything? Make it a little more foreign, undecipherable, far away?

This is a poem that’s concerned with its own “poem-ness” (see its opening, the suddenness of its shifts between modes): moments of it are pure Romanticism, first-person-voiced to an unnamed beloved, honest and open (as if these categories… well, anyway). There are moments of text, just text, entirely text (most of them would be quite a stretch to vocalize). The poem explicitly brings up readability, context, clarity, invention, gestures. For a short enough poem (five pages with few words on each), this seems no accident to explicitly bring up these categories of inquiry.

Also in this poem, there is a gray block on the last of its three pages (just gray; a solid rectangle), and the poem ends

For gestures words are

a birch path here

à

So suture an “alum gown”

ààààà

What about these à-s? I couldn’t help hearing them. Hearing them, maybe, as bird notation? notation of bark beetles scraping away inside a tree? Or as notation for something else, something more conceptual, harder to access? Like the whole movie The Matrix was in my throat or gut? Maybe that’s just me.

---

Flipping through the table of contents, I expect you’ll have a similar experience that I did: there were many names I recognized (and was excited to see what they did in this company, in the context of “the postmodern pastoral”) and some names, too, I didn’t recognize. The anthology can serve as something of a “Who’s Who” of smart, on and tuned-in, rad poets who are writing now. And what’s more, the curation and collection of this book is a little like one of those amazon.com algorithms that says “If you like [x], you’ll maybe be interested in [y].” One poem in The Arcadia Project will comment on a previous poem, build upon what was started. Disparate voices make the expected and delightful frictions, but maybe more compelling to me is that similar voices are allowed to be similar and proximate (in part because each individual poem is so good at standing on its own that there is no threat of redundancy inherent in the similarities). I was excited by what I found from the voices I was already familiar with and—I think even more importantly in terms of the effect of a book like this—blown away by the poets whose names I now have in a little list next to my bookshelf.

This is a masterfully curated anthology. I suspect that few people sit down with anthologies—particularly the ones wider than Paradise Lost—to read them from cover to cover. In this case, however, I highly recommend it. The careful curating of each section, and the conversation across sections, along with the sparseness of “extra” materials makes this an anthology that must, and can, and does speak mostly loudly through its poems and their sequence, their conversation.

We go to poems for different things. We go to “nature poems,” to “new” or “postmodern” poems, for different things. But these poets, poems, pages, in all their complexity, sincerity, use of the tools available to the 21st century poet (all of them!), offer plenty, in range and in quality, to their readers: the 500-plus pages of this anthology miraculously do not include a dud; a poem that fails to challenge and excite and spark something new.

---

1 Uh oh, “consumers.” That just slipped out.

2 These are all pleasures I indulge in. I am not better than you. My web-browser is open to Patagonia fleeces on sale at REI.com.

3 Do you remember how beloved The West Wing was? The West Wing, the oddly and appealingly utopian show about politicians who spoke complexly, quickly, passionately, and at great length, about the issues that confronted our nation? Democratic politicians who, through lightning-fast discourse and group decision-making, unfailingly did the right thing? The West Wing premiered in September 1999, and was wildly popular for the first six years of George W. Bush’s presidency. Critics have both celebrated and derided The West Wing for being unrealistically optimistic and sentimental (indeed, “insufferably high-minded” was one critic’s assessment). Sure, this is escapism in the form of a 50-minute glossily-orchestrated spectacle (with such handsome faces)… but is it escaping to the easier place?

4 Please see the astounding Joyelle McSweeney’s contribution to this anthology, and also see her blog, for more on the necropastoral.

---

Hannah Ensor lives in Tucson, Arizona. She is the author of no books, and is an MFA candidate at the University of Arizona. You can read more of her writing here, here, here, collaboratively here, and forthcoming here.

The Arcadia Project was edited by Joshua Corey and G. C. Waldrep.

Joshua Corey is the author most recently of Severance Songs (Tupelo Press, 2011), which won the Dorset Prize and was named a Notable Book of 2011 by the Academy of American Poets. His other books are Selah (Barrow Street Press, 2003) and Fourier Series (Spineless Books, 2005). He has recently completed his first novel and lives in Evanston, Illinois with his wife and daughter and teaches English at Lake Forest College.

G. C. Waldrep's most recent full-length collections are Archicembalo (Tupelo, 2009), winner of the Dorset Prize, and Your Father on the Train of Ghosts (BOA Editions, 2011), a collaboration with John Gallaher. His most recent chapbook is "St. Laszlo Hotel" (Projective Industries, 2011). He lives in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he teaches at Bucknell University, edits the journal West Branch, and serves as editor-at-large for The Kenyon Review.

Read/learn more here.

People Are Places Are Places Are Peopleby Jeff Alessandrelli

Imaginary Friend Press, 2013

People Are Places Are Places Are Peopleby Jeff Alessandrelli

Imaginary Friend Press, 2013

The Louisiana PurchaseJim Goar

Rose Metal Press, 2011.

The Louisiana PurchaseJim Goar

Rose Metal Press, 2011. Shore Ordered Oceanby Dora Malech

Waywiser Press, 2009

Shore Ordered Oceanby Dora Malech

Waywiser Press, 2009 O Bonby Brandon Shimoda

Litmus Press, 2011

O Bonby Brandon Shimoda

Litmus Press, 2011 Cloud of InkBy L.S. Klatt

University of Iowa Press, 2011

Cloud of InkBy L.S. Klatt

University of Iowa Press, 2011 Thunderbirdby Dorothea Lasky

Wave Books, 2012

Thunderbirdby Dorothea Lasky

Wave Books, 2012

The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoraled. Joshua Corey and G. C. Waldrep

Ahsahta Press, 2012

The Arcadia Project: North American Postmodern Pastoraled. Joshua Corey and G. C. Waldrep

Ahsahta Press, 2012

Humanimalby Bhanu Kapil

Kelsey Street Press, 2009

Humanimalby Bhanu Kapil

Kelsey Street Press, 2009

Half of What They Carried Flew Awayby Andrea Rexilius

Letter Machine Editions, 2012

Half of What They Carried Flew Awayby Andrea Rexilius

Letter Machine Editions, 2012 Ten Walks/Two Talksby Jon Cotner and Andy Fitch

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2010

Ten Walks/Two Talksby Jon Cotner and Andy Fitch

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2010 Honorary Astronaut

by Nate Pritts

Ghost Road Press, 2008

Honorary Astronaut

by Nate Pritts

Ghost Road Press, 2008 darkacre

by Greg Hewett

Coffee House Press, 2010

darkacre

by Greg Hewett

Coffee House Press, 2010 Echo Gods and Silent Mountains

Patrick Woodcock

ECW Press, 2012

Echo Gods and Silent Mountains

Patrick Woodcock

ECW Press, 2012 Nothing Is In HereAndrew Levy

EOAGH Press, 2011

Nothing Is In HereAndrew Levy

EOAGH Press, 2011 Canarium Press, 2012

Canarium Press, 2012