CUTBANK INTERVIEWS: A Conversation between Alexandra Teague and Pamela Huber

October 20, 2023

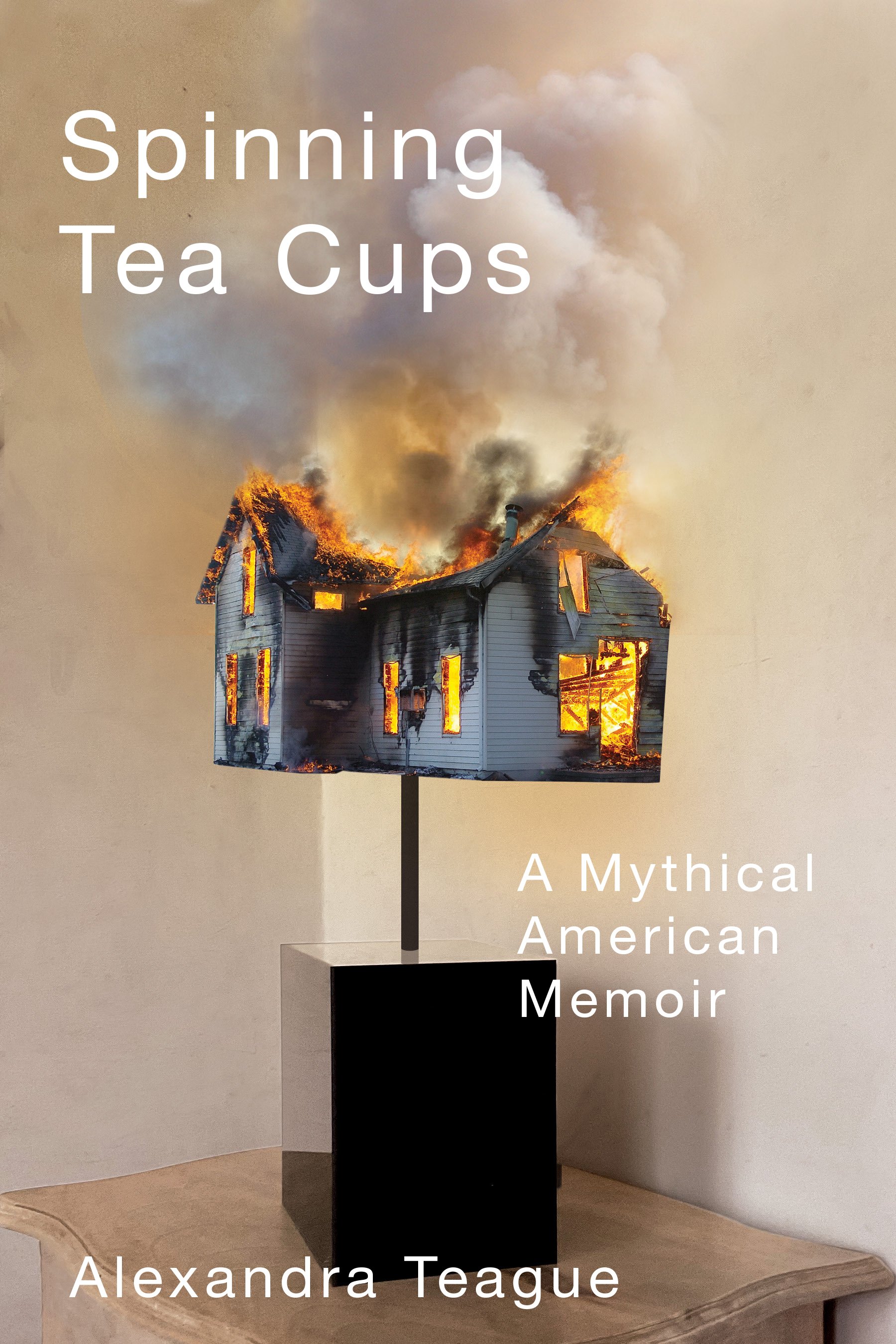

Alexandra Teague’s most recent book is Spinning Tea Cups: A Mythical American Memoir (Oregon State University Press, Oct. 2023). She is previously the author of three books of poetry—Or What We’ll Call Desire, The Wise and Foolish Builders and Mortal Geography—and the novel The Principles Behind Flotation, as well as co-editor of Bullets into Bells: Poets & Citizens Respond to Gun Violence. She is a professor at University of Idaho, where she co-directs the MFA program.

Pamela Huber: Your mother looms large over Spinning Tea Cups. In your “Tea Cups” essay, you say she may have “said everything as ‘gospel truth’ as a coping mechanism to control the narrative, to control us, to make us doubt our own perceptions so we’d lean on hers.” How do you see this memoir as a reexamination and reclaiming of your own perceptions? What was the process of re-perceiving like?

Pamela Huber is an MFA candidate in fiction at the University of Montana. She was raised on the water, on Lenape land in Delaware, and educated on Piscataway land in Washington, DC. Her writing has appeared in Atlanta Review, Furious Gravity, The Journal of Lost Time, Beyond Words Literary Magazine, Delaware Bards Poetry Review, CommonLit, and elsewhere. She has received awards from Glimmer Train and been nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

Alexandra Teague: I’ve often joked over the years that I became a writer because my mother was such a good storyteller and talked so much that I couldn’t get a word in edgewise in my family. The only way that I could ever tell my story was to sit down and write it.

This is definitely the most in-depth I have ever analyzed my stories and tried to reclaim them. The process was very challenging. I wrote and rewrote these essays over the course of about five years.

I had a year-long sabbatical from the University of Idaho, where I was living in Cardiff, Wales. It was very useful to be across the world from my usual context and able to do a lot of reading and thinking about subjects related to these stories while walking around the city. Walking with my thoughts is also very good for my writing process.

The central crux for me was doing justice to the ways in which my family was, and is still, very wonderfully imaginative, and has many fantastic and fantastical aspects to it. Doing justice to that and sweeping the reader up in the ways that are very beautiful without, as I say in some of the essays, ending up feeling like I’m just replicating those same fantasies.

But then I was also not wanting to replicate what I feel my mother did, which is just presenting her narrative as the absolute truth. I’m very conscious that I’m writing about other family members who have their own versions of truth and their own versions of these same experiences.

A lot of what I struggled with in writing and rewriting these essays is trying to create enough space for the kinds of questions that felt important to me where I wasn’t just running with a single narrative and where I was allowing multiple versions to coexist, or my questions about my own versions to coexist. I hope I’m not just replicating my mother’s versions, the fantastical versions, in an unquestioned way.

PH: Spinning Tea Cups is concerned with the “dangerous and recuperative powers of fantasy.” In your book you say you were “trying to look rationally at fantasies I’d been raised with.” You also say “for fantasy to retain its power, it can’t be questioned or de-symbolized.” What’s your relationship to fantasy now after questioning your family’s fantasies so thoroughly in Spinning Tea Cups?

AT: The interest in questioning fantasies and cultural stories and family stories has been present in my last two poetry books and in my novel. But having to really stake claims about what I think about various types of fantasies that I was raised with and cultural fantasies—what I think about escapism and the ways that we touristically, in our culture, cycle certain ideas of what is ideal or what is fun or what is fantastical back through the culture—got really complicated in the process of trying to write about it in essays. Because, again, I had to stake claims more, I had to say more what I really thought.

That essay “White Rabbit, White Rabbit” that’s about two thirds of the way through the collection is the one essay I really did not plan to write. I knew that there needed to be an essay called “Space Mountain” and knew that there needed to be essays about a number of the other subjects. But “White Rabbit, White Rabbit” found me. That’s the essay in which I most had to reckon with this idea, because I wrote that in response to the fact that some things that seemed very uncanny and fantastical happened to me in the process of writing the book. Namely, it seemed as though my young nephew, whose suicide is one of the main subjects of the book, wrote me a letter in the midst of working on this.

The part you just quoted felt like it undercut my rational approach, to say "and yet in some part of me, I do believe there's some kind of communication with the dead."

In a letter he wrote, my nephew makes a comparison between love and ghosts, and I say “what if ghosts are just another way to express our ongoing love for the dead?” I think part of what I come to is: whatever kinds of fantastical things are true, and whether or not ghosts are real, I do believe in the power of writing and trying to tell our stories of the people that we love now, and the people that we love and have lost, and earlier generations, as a way of continuing to express our love and continuing to have connection and communication—whether that’s an uncanny sort of communication—that is still real.

PH: Keeping the questioning alive?

AT: Yes.

PH: Your essays have large or small allusions to Walt Disney World, both in the titles and the contents of your essays. Was this an early choice or an undercurrent of fascination with fantasy and escapism that slowly emerged? How did Walt Disney World succeed and fail as a frame for your memoir?

I thought of Disney World immediately. The first essay I wrote is the coda, “Panharmonicon.” I wasn’t meaning to write an essay, or I wasn’t meaning to write a collection of essays. Shortly after that, I thought of the other ones. “Perfect Storms” was originally called “The Jungle Cruise.” “Frontierland” has always been called “Frontierland,” and “Space Mountain” has always been called “Space Mountain,” so early on, I knew the titles for some of these essays and knew that I wanted them to be in conversation with Disney rides.

“20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” I think was the second essay I wrote and I hit on the structure, in that, of going on the Disney ride as part of what I was talking about in terms of repetition and eternal return and the cyclical nature of grief within my family surrounding my grandfather’s death. I found that structure but I of course didn’t want to do the same thing in all of the other essays. I didn’t want it to become this gimmicky thing of mimicking the rides. So it was definitely a process of figuring out to what extent Disney belonged with each of the subjects and how it worked as a framing if it didn’t belong with some of the subjects.

The reason that Disney felt really central is that not only was my family really interested in going to Disney World, but also I’m really fascinated—partially from growing up in a tourist town in the Ozark Mountains, and partially from having traveled to a number of touristic places and Disney World—I’m interested in how spaces like that both are escapes from the dominant culture and also create metaphoric versions of things in the dominant culture. I felt like Disney was a potent example of something that a lot of people in our culture can relate to in different ways.

Jen Brych, one of my primary readers, has never been to a Disney park, so it was actually really great for me because she said, ‘I know about Disney things but I don’t know what any of these rides are, so you have to also explain them enough to me that it makes sense.’ Because not everyone is steeped in Disney.

I did a lot of reading about Disney World and one of the books, Vinyl Leaves: Walt Disney World and America by Stephen M. Fjellman, is a really fascinating analysis of the parks, the construction of the rides, and how fantasy plays out in all these different ways. Thinking about this book in relation to family stories helped me figure out how to weave Disney into the essays. “Space Mountain” does take the rollercoaster as a driving metaphor and a means of moving the essay. I didn’t come to using the rollercoaster as a means to move the essay until many drafts in. And then in some of the other essays, there’s more initial framing that has to do with the overall metaphoric structure of the essay.

PH: You’ve said in a past interview that research “provides a rich source of language and strange facts and images that it almost felt like cheating.” I was hoping you could speak more on the research required of these essays. Especially for the half-dozen locales that you travel back to, including Missoula and the University of Montana.

AT: I do think for my poetry, which was the context in which I said that research often feels like cheating, that it does because there’s so much strange and fantastic language out there when you start reading other sources, particularly historical sources, that is so wonderful to draw on for writing, that’s way more imaginative than anything I would come up with on my own. I feel like that’s true for the essays because the research took me in a number of directions I would not have thought about going on my own. And also, it really deepened threads in the essays.

I did a lot of reading into my grandfather’s death, finding primary documents. That’s a story I’ve been raised with, about his death on the Mt. Hood ammunition ship that exploded in World War II, but I hadn’t read the documents giving accounts of the explosion until I worked on this essay.

In one way it made the essays easier to write, but I also think that I feel less like the research was a cheat than I do in my poetry because it also provided so many possible directions the essays could go. One of the reasons that I had not written nonfiction before is I’ve always felt I would have a sort of agoraphobia if I was writing nonfiction; I would be out in an open space in which I could go in any possible direction, and how do I try to reign that in?

I’m very interested in form—not just conventional form, but how form shapes meaning in poetry. Trying to find the right form for each individual essay is a struggle. And then all the different directions that I could go depending on which sources I lean on, where the research takes me, just opens it up even further.

So I found research very helpful and also sometimes surprising and sometimes overwhelming.

In terms of the many places I went, one of the big things that I did work on in later rounds of revision was making the places feel as inhabited as I could. I’m very interested in place and have lived in a lot of different places, including Missoula briefly for six months as an undergrad. I realized in the process of getting feedback—this is the most basic show don’t tell advice that everybody gets in creative writing classes, and that we all give—how much I take for granted [the idea] that everyone’s been to a New Mexican ghost town and everybody has some idea of what Missoula feels like and everybody has an idea of what an Ozark tourist town feels like. I’m writing about these places that I know quite well and trying to then make them feel very inhabited and real to other readers. It took, often, a lot of research to figure out how to give grounding details that were beyond just what I might have experienced in that place in the limited amount of time that I was there.

PH: Did you find any new realization about Missoula in particular as you were doing your research?

AT: I don’t think I found anything in doing my research. But I will say that living just four hours away from Missoula now and going there sometimes at this stage of my life and getting to be there for the book festival has allowed me to develop a very different relationship with Missoula than I had at the time that I was there. And it’s interesting for me now because one of the things that I describe in that essay “Wings” is feeling like I was on the other side of the Rocky Mountains from everybody and everything that I knew. The Rockies felt like this really stark divide between me and the life that I’d known, more than I had expected them to feel when I moved there. And of course, now I’ve lived for more than two decades on this side of the Rockies, so I think I just have a different association now. And I’ve had to ask myself a lot of questions about how I feel about being someone from the West, because that’s become more and more of my identity, and it wasn’t at all at the time that I was there. And that turns up in other essays too: questioning Western identity.

PH: This latest book marks your triple crown of publication: you have three poetry collections, a novel, and now a creative nonfiction memoir. How do you approach genre throughout your career, and how did your previous publications impact your latest work of nonfiction? Were there ideas in Spinning Tea Cups you tried to address in your other work and how did the different genres impact your ability to write about these topics?

AT: Spinning Tea Cups came partially out of subjects I started writing about in Or What We’ll Call Desire, my third poetry collection that came out in 2019. My nephew had committed suicide while I was working on that collection. I thought that collection was much more about gender and visual art and some other related themes. When I started writing poems about him, and going back and talking to his brother, I realized that there was so much about our family that I had just been kind of able to glance off of in my poems. There were things that I was starting to say but wanted to explore much more.

So the nonfiction really grew directly out of that project and a desire to be able to speak more directly about Gabriel’s life, but also these questions of how these beautiful aspects of fantasy and storytelling and imaginativeness in our family meant that we also didn’t talk openly about things that crossed the line into mental health issues and maybe some real dangers and some abusive situations that also happened in my family. I wanted to be able to slow down and figure out a way to talk about those more, partially to honor Gabriel’s life. Some conversations I was having with my sister and my nephew [were] making it increasingly clear to me that there were a lot of layers to the family that didn’t match up with the sort of stories that my mother had mostly told me, and that I was missing a lot of context about the family too. So I wanted to slow down and write that.

My preoccupations with how fantasy and people’s actual lived lives affect one another and cycle through one another has been a preoccupation starting with my second poetry book. The Wise and Foolish Builders looks at questions of westward expansion and mythologies surrounding Sarah Winchester and her house in California. So that [book] and So What We’ll Call Desire take on those themes. Then my novel, The Principles Behind Flotation, is set in a tourist town, which is very much like the one that I grew up in in the Ozarks, but then also has this other magical realist layer that heightens the questions about what is real and not within that town. So the novel allowed me to create a whole world that asked some version of these questions. My poetry has allowed me to get at a wide range of themes and history related to them. And the memoir has allowed me to take those questions deeper and more personal. It’s forced me to really question where I fit within these questions.

PH: I wanted to let you know, I had two moments of synchronicity reading your book. The first was Sarah Winchester came up and I had just read The World is On Fire [by Joni Tevis], which has the opening essay on Sarah Winchester’s house. I found that fascinating that that was a previous research subject of yours. And the other was me talking about the logic in Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll the day before reading “White Rabbit, White Rabbit.”

AT: Oh my god!

PH: So I had synchronicity reading your essay on synchronicity.

AT: That’s perfect. I absolutely love it.

PH: Your poetry collections often experiment with form. You’ve said in a past interview that “using (particularly repetitive) forms is often about peeling away layers in a way that feels generative,” and “form does help revisit or approach pain and violence and tragedy and the language we use to speak about them, and what we’re willing, or able, to say the first time we’re asked, versus the second.” How did the essay form build on or challenge this view of repetition as you circled around topics of family and fantasy in your essays?

AT: Slowing down in the essays—needing to say more about what I thought about each of the subjects, and what I thought the valuable questions about them were—really built on my sense of what repetition can do.

I was just teaching pantoums in my prosody class this past week and we were talking about this idea. Getrude Stein of course says that “there’s no such thing as repetition; there’s only insistence.” We can’t say the exact same thing again. So we say something once and then we return to it again, in a repetitive form like a pantoum. It has to be in a different context the next time, which inherently is going to shift what we’re saying about it. But it also might lead us to say something different and maybe truer of it the second time. Especially in a project that is so much about questioning received stories and questioning truths.

Some of these essays work through types of repetition, but some of them work through a pretty conventional, essayistic way, approaching material and saying well this is one possibility. Like in “Tea Cups,” about my mother’s self-proclaimed psychic abilities, saying: maybe it’s true that she really did see such and such; maybe it’s true that it’s her emotions; maybe it’s true that she was trying to control the narrative; maybe it’s this other thing. The essay form gave me space to keep returning to questions, and providing different possible answers, and testing those out in different ways. Or admitting that those can all coexist and there are answers that I’m never going to really know. But [I can] try to figure out, what kind of meaning do these stories still have for me if I’m not going to get to some kind of bottom, bedrock truth? That’s what happened in “White Rabbit, White Rabbit.”

One of my all-time favorite quotes is James Baldwin saying, “the purpose of art is to lay bare the questions that have been hidden by the answers.” I think that’s part of what returning to the same subject matter allows us to do.

PH: I want to touch a little more on form in these essays. Recently my creative research class was talking with Joni Tevis about secret shapes in essays. You’ve mentioned one of your essays, “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea,” using the shape of a Walt Disney World ride. Another one of your essays, “Building Character,” uses a two-act play as a shape. Are there other secret shapes in your essays that we should be on the lookout for?

AT: Part of “Frontierland” uses a variation on the exquisite corpse game that my family plays. Somebody writes a sentence and then somebody else draws a picture of that sentence. And then the next person only sees the picture and then they write a sentence of what they think it is, and so on. It’s a telephone-like situation in which you get further and further from what was originally there. I used that form of the folded paper and also the form of the animatronic presidents speaking in the Hall of Presidents, giving these pre-recorded, masculine addresses. So I take on both those [forms] at some point in that essay. I talked about “Space Mountain” and the rollercoaster. “Building Character” came to be a two-act play late in revising. I realized that it needed to do more with the theater aspect of it.

[In “White Rabbit, White Rabbit,”] I take on the metaphor to some extent of the “collages in the open,” which is language Jacob Bews used to talk about Jan Svankmajer’s stop-motion animation where you can see that the creatures in Alice in Wonderland are created from other creatures, and you can see all of the parts that don’t quite fit. I say “what can I do but make a ‘collage in the open’” of my “mismatched pieces of logic and emotion,” but to some extent that becomes a shape for that entire essay, which is more fragmented than any of the other essays are. I wrote and rewrote many times before landing on that more fragmented structure.

I definitely wanted each of the essays to move in a distinct way, but I also find that one of the hardest things to figure out.

PH: Are you returning to poetry after this? Do you feel you have exhausted nonfiction for the time being? What is next for you?

AT: I have a collection of poetry that I haven’t officially announced yet. Persea Books, which has published my first three collections, has accepted another collection which will be out next year, so I will be working on edits for that. Then I’m wanting to work on a longer poem. I just know there is a longer poem that I eventually want to write. I don’t know what it looks like or sounds like yet, at all. I’m tentatively moving toward that. But I don’t think I’m done with nonfiction. I’ve written a few very short shorts which is extremely different than these essays. I’m interested in exploring shorter-form nonfiction at some point too. I sometimes teach a genre-bending class at UI and I’m interested in work that plays between genres. Although I do less work that’s hybrid myself, I am interested in the affordances of different genres and would like to keep exploring all three of the genres that I’ve written in.