CUTBANK INTERVIEWS:

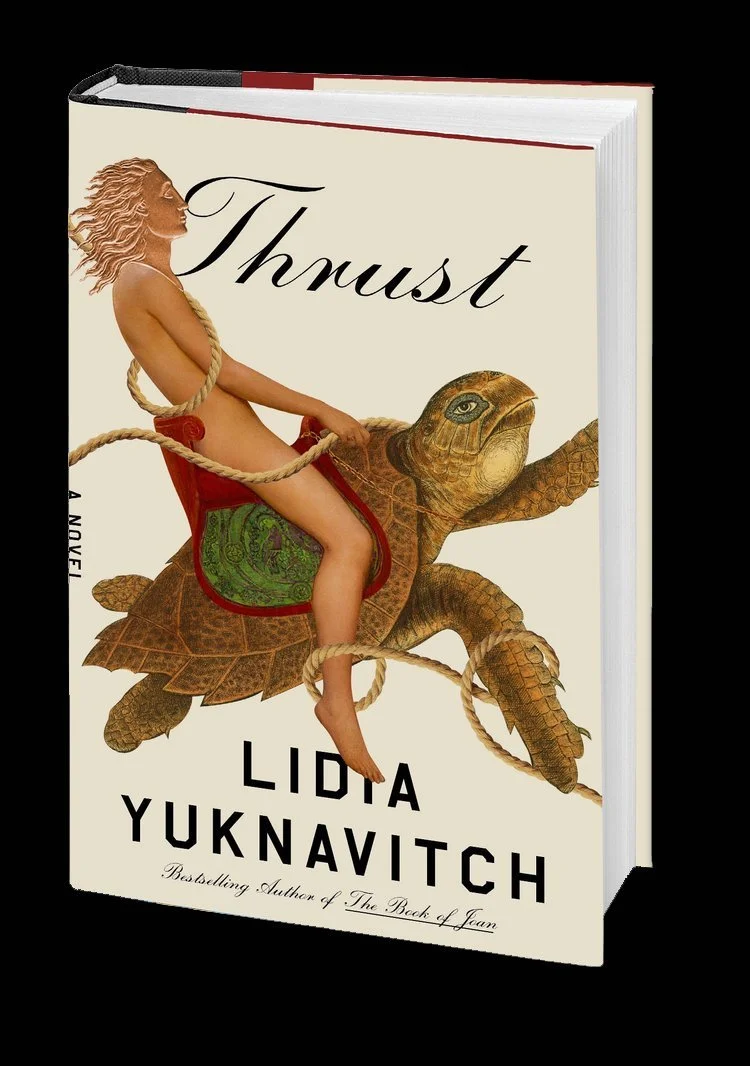

Lidia Yuknavitch is the National Bestselling author of the novels The Book of Joan and The Small Backs of Children, winner of the 2016 Oregon Book Award's Ken Kesey Award for Fiction as well as the Reader's Choice Award, the novel Dora: A Headcase, and a critical book on war and narrative, Allegories Of Violence (Routledge). Her widely acclaimed memoir The Chronology of Water was a finalist for a PEN Center USA award for creative nonfiction and winner of a PNBA Award and the Oregon Book Award Reader's Choice. The Misfit's Manifesto, a book based on her recent TED Talk, was published by TED Books, and her new collection of fiction, Verge, was released in 2020. Lidia’s newest novel is Thrust.

A Single Thought Can be a Portal: An interview with Lidia Yuknavitch

December 8th, 2023

“Portals are everything. Even a single thought can be a portal. A single word. You know, the way poetry moves.” - Lidia Yuknavitch, Thrust

Lidia Yuknavitch is the multi-genre author of the acclaimed memoir The Chronology of Water, the short story collection Verge, and the national bestselling novels The Book of Joan, The Small Backs of Children, Dora: A Headcase, and Thrust. She received her doctorate in Literature from the University of Oregon where she published a critical book on war and narrative, Allegories of Violence. She is also the author of The Misfit’s Manifesto, a book based on her TED Talk, the cofounder of multiple literary zines and magazines, including Northwest Edge, and the founder of the workshop series Corporeal Writing in Portland, Oregon.

Lidia generously sat down with CutBank’s Editor in Chief Jenny Rowe and Interviews Editor Pamela Huber to discuss craft, publishing, and her latest book, Thrust. Their conversation spans the space between memory and imagination, the death of the hero’s journey, and the duty of today’s writers to keep the pilot light of storytelling lit.

——

Lidia Yuknavitch: I just want to say, hurry up with your books, because we need you.

Jenny Rowe: Aw, thank you so much.

Pamela Huber: We appreciate that. So, our first question: Most adult authors remember what it was like to be a child with a body, with curiosities and pleasure and pain and trauma, and our society may be opening the door a crack for the traumatized child’s body, but it still seems to be slamming that door shut regarding childhood corporeal pleasure. How have you approached considering the child’s body as an adult author, especially with your child protagonist in Thrust?

LY: Yeah, that’s a real flash-point character. I’m of the opinion that sexual development happens the moment we come out of the shoot, or however you enter the world, because we’re biological creatures. And we’re emotional and psychological creatures. And we have drives. But I think that about animals and about trees and about the ocean. And so my constant effort is to keep the space of sexuality open as if it’s as vast as space or the ocean. And so when I direct that energy toward child figures or teen figures or youth, I’m thinking of it in a developmental stage way, as as open as possible, and as exciting and passionate and erotic as possible, and trying to ask, how many stories live in that space instead of asking what’s the one mono-story we can tell so everyone will be safe and quiet and we don’t have to admit that children even have sexuality at all? I’m not the only person on the planet who’s interested in trying to hold open that space for as many stories as possible. But, as you say, not everybody’s comfortable trying to ask what are the variety of stories? Especially right now, there are actual forces that are trying to shut down what we mean by sexuality. And so it seems even more important to jam your foot in the door and try and keep it open so that more stories, not less stories, can emerge. And I also think we haven’t even begun to touch on what’s fully possible in terms of the story of sexuality at any age. I mean, I’m 60 now. We also culturally don’t want to hear about the oldies. And you know, what’s up with that? I’m not dead yet. We have stories to tell, and they don’t fit the traditions we’ve inherited. They don’t fit them at all.

JR: As a follow-up to that, we read in a previous interview of yours that you said about language and grief, “The best we can do is bring language in in relationship to corporeal experience. Bring words close to the body, as close as possible, close enough to shatter them.” I love that quote, by the way. We were both just so struck by Chronology of Water. In the 13 years since you wrote that book, how has your view on the role of corporeal language evolved, particularly in regard to pleasure, compared to Thrust?

LY: Well it’s ever evolving, though I still think it’s true: the best we can do is bring language close to the body. But let me kind of shift the lens on it. I also think the body itself is a metaphor for all experience. And when I say that partly what I mean is that we walk around in these meat sacks. But it’s how experience is mediated for humans, humankind, for human beings. Language is a step away from that. But the body itself, because we have senses, is a kind of vehicle for meaning making.

And I don’t think it’s completely separate from other bodies that exist in the world like trees and rocks and animals and weather. There are bodies of water, there are bodies of plant life, there are mycelium that are older and smarter than us. So when I say body, I don’t even just mean exclusively human. So if a body is a metaphor for experience, and we’re asking questions about pleasure or pain, I’m very interested. One way my thinking continues to evolve around this question is, What happens when you loosen the binary? What happens when you stop acting like pleasure and pain are opposites or binaries? And what is the kind of more fluid—again opening up an array of stories and experiences—approach to this question of pleasure or pain?

Jenny Rowe (she/her) just completed her MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of Montana and has returned to Iowa City to work for her favorite bookstore, Prairie Lights. She was the 2023-24 editor in chief of CutBank literary magazine, and she's currently querying agents for her memoir manuscript about living in Beijing prior to the pandemic. You can find her recent work online at Touchstone, and she has another essay coming out in THR (The Hopkins Review) near the end of 2024.

Pamela Huber is an MFA candidate in fiction at the University of Montana. She was raised on the water, on Lenape land in Delaware, and educated on Piscataway land in Washington, DC. Her writing has appeared in Atlanta Review, Furious Gravity, The Journal of Lost Time, Beyond Words Literary Magazine, Delaware Bards Poetry Review, CommonLit, and elsewhere. She has received awards from Glimmer Train and been nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

The trickiness is, we like language to nail meanings down. We like it. It feels good. It feels good to be clear. It also feels very male to be clear, because the definition of who gets clarity and who doesn’t has been locked in a kind of patriarchal order. So I’m asking questions as I try to evolve my own curiosity away from binaries and toward varieties of meaning making, using language to open up expression.

Poetry just does that. It rearranges language in a nonlinear way, without the focus being on clear communication, but rather on sensory perception, color, rhythm, repetition, fragmentation. Those poetic forms already do what I’m talking about. But I’m a shit poet. So my explorations are in prose and painting and drawing, and not so much in poetry. But I learned most of what I’m curious about from closely watching how poets and poetry works.

PH: It reminds you of your quote about exploring the body’s point of view.

LY: Yeah. I mean, it’s a really simple shift to take what we think we know about point of view, and then ask, What if the body has one that’s not like your thinker brain. It seems like a really simple thing to do, but it’s not simple at all, because my shoulder may have thoughts. My abdomen or my hips may be carrying stories that my conscious mind is unwilling to plug into, except in certain circumstances. So corporeal writing grew out of that idea that our bodies are holding everything that’s ever happened to us. And there’s more than one way to access those stories.

PH: And then put them back into language which comes from the mind again.

LY: That’s what I mean. Language is always going to be tricky because it’s language and it’s ordered and it has grammar and it has sense and it has logic, but I love best the language that rearranges.

PH: I first discovered your writing on a recommendation from Pam Houston who you share some trauma-informed themes, particularly escaping the homes of alcoholic mothers and abusive fathers. What I admire about both of you so much is your ability to turn the ugliest of human nature and taboo subject matter into rich and beautiful language, as you said, “alchemize the dark and turn it into something beautiful and smoothy you can carry in your hand.” And then you say of the incest and abuse narrative, “We all move through the waters. Language makes us feel less separate.” And then, in a joint conversation with Pam Houston and Cheryl Strayed, you said, “If you tell your story, and you’re a woman, and you were victimized, the idea that your only position is ‘victim’ is bullshit.” With all that in mind, can you speak more about how your writing has allowed you to disrupt that forced victimhood narrative?

LY: It’s difficult to talk about, partly because you don’t want to say that people who have been harmed have not been harmed, and you don’t want to walk around saying the people who do the harming don’t matter. So let me just say that first: all of that matters deeply and profoundly, and some people we have loved couldn’t live with it. They had to let go. So let’s just set that aside as true, forever.

But when I say the “victimhood narrative,” I’m talking about a construct, like a story that’s sitting out there in the world waiting for you before you’re born, that at its worst can suck you into one version of how to experience your own trauma or pain. And if you don’t line up with that one version, there’s something wrong with you. Or if the story you have to tell deviates from that [narrative of] “sickness and health” or “you were harmed, and here is how you heal, and when you heal you will be transformed in this specific way,” [then] that’s a dangerous space from my point of view. Because what I’ve learned from interacting with people who’ve experienced trauma or pain or something awful, like war, or torture, or addictions, or depressions, is that there are hundreds and hundreds of ways to tell the story, and they’re all needed so that we feel less singled out if ours doesn’t conform to the most popular version of the story.

And so when I say the “victimhood narrative,” I mean the one that gets the most air time or is bought and sold on the market the most, that covers over the varied, contradictory, not always pretty, antagonistic, or even pleasure versions of stories of what has happened to us. And they don’t all agree with each other, and that’s how it should be. My worry is that this story that gets most air time or sells, or gets the weight of the culture, shuts down all the other stories that don’t agree with it, and I think that’s dangerous. I think that shuts down human experience and disallows for the fact that our stories aren’t going to agree with each other.

PH: So we both read Thrust—

LY: (joking) Are you alright?

PH: (laughs) Yes. We were just rereading it before you came in, letting the language wash over us.

LY: So you know, I know it’s a weird book.

PH: It’s fun, though. I do think two-thirds through it, I still didn’t know what the point was. And then I got to the end, and I was like, Oh, it’s the point that I didn’t know what the point was until the end! It’s fun that way.

JR: Yeah, I would agree.

PH: It’s a puzzle.

LY: That’s a good way to put it.

PH: Oh, thank you. One thing Thrust is concerned with is how we save and protect ourselves and one another. And you’ve critiqued the role of redemption in religion and in storytelling. And so how have you found yourself resisting that narrative arc of redemption, especially in fiction?

LY: Well, fiction is the one place you’re allowed the space to resist redemption. The basic setup of a beginning, middle, end, seduces you toward storylines of redemption, and the basic formulation of a singular hero on a singular journey pushes you toward the redemption narrative. So part of the structure of Thrust is to refuse the single hero, the single hero’s journey, and the structure of a beginning, middle, and end. Because that is the sin or difficulty [of the] “overcome it” redemption framework. The traditions we have inherited for the novel have that framework. And so every time I write a novel, I’m in it to write against the grain of that fundamental structure. To shake loose the idea that experience is polyphonic. That people’s experiences interrupt and disagree with each other. That the notion of a singular hero is bogus at best, even though it feels good to read about them—it feels good! It’s like, Oh, there’s a hero! This feels so nice—And we want to know what happens! And we could pretend to be heroes! Which no one is ever able to achieve. Stories and experience are polyphonic, they are not singular in terms of the heroic journey. The heroic journey itself doesn’t meet up with the experiences of legions of people, usually underrepresented populations. It actually subsumes the experience of marginalized people.

So every time I embark on a novel project these days I’m like, What can I do to disrupt the whole shit house? It’s like what a Russian theorist from a long time ago named M. M. Bakhtin called heteroglossic, meaning the novel is many-voiced and the plotlines crisscross and the discourses get louder or softer in a kind of symphony.

And the novel is one of the only places you can achieve that, except maybe a weird experimental film. I can think of “Wings of Desire”—which, if you haven’t seen, you should watch tonight—makes that symphony of story and voice and character. And a lot of innovative writers are invested in the same project. It’s not just me. I have heroes in this area. But that’s what I’m up to in terms of your question: the novel is both the place that can shut possibilities down and make everything sound the same, but it’s also still the place where you could interrupt all that and keep showing people [that] stories are multiple and loud and interacting. And so that’s what Thrust is trying to do.

Although I would suggest [Thrust] has a couple of main themes. Main thrusts? It’s a little bit of a love letter to the laborers who were involved, at different points in time, in trying to contribute to the story of who we are, but they get erased and absorbed by celebrities and heroes and rich people and famous people. In some ways it’s just a love letter to laborers and people who are small and quiet and erased easily.

PH: You also said somewhere like writing Thrust with polyphonic voices changed how you’ll write novels forever. What has it been like moving forward in your new writing since completing Thrust? How has that seeped its way into your experimentation with form now?

LY: I’ve pretty much let go of the idea of a singular hero in my storytelling. I’m very suspicious of that idea now. I’m not very interested anymore in the hero’s journey. There’s an essay by Ursula K. Le Guin, who was my friend and mentor, and I miss her a lot, called “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” I’m sure you’ve seen it. That’s not the hero’s journey. That’s the suggestion that storytelling could take much different forms than the ones we all know about that we’ve inherited. So I’m interested in multiple voices versus a singular hero, stories crisscrossing versus a singular hero’s journey, and a resistance of the redemption narrative which you’ve pointed out as well, in favor of storytelling acts that open up questions and possibilities rather than present redemption or transformation in a way that we’re all gonna fail at in regular life.

JR: I’m gonna shift into craft. In both Chronology of Water and Thrust, there’s definitely a nonlinear story structure going on, and you called it literary fragments before. I noticed with the interview you had with Rhonda Hughes at the end of Chronology of Water, you said, “nonfiction and fiction are as inextricably linked as memory and imagination. They use the same brain circuits when they are active.” I’m curious, what does fiction allow you to do, in terms of literary fragments, that nonfiction maybe doesn’t to the same degree?

LY: It’s a question that I know interests a lot of people, and there are important debates about it, too. I will say, for my own part, that nonfiction employs the same kind of toolbox as any kind of writing. But in nonfiction you have some allegiance to what happened to you. And even that is not stable. As we know, from any kind of family holiday dinner where everybody experiences the same thing and no one tells the same story. Right? So in nonfiction, some doors are closed to you only because it didn’t happen or the choices you make about telling can’t go out of orbit from what the experience itself was. Except that there are some innovations in nonfiction writing, some kinds of writers who like to play with that notion, and I would place myself kind of in that territory because I’m always asking questions about the stability or trustworthiness of memory. And in that way, memory and imagination are not separate. They have a kind of dance.

And I would argue that as you write a nonfiction story you are curating. So you’ve got memory not being stable and being close to the imagination, you’ve got the fact that you’re curating memory. And at that point you have to at least admit there’s a relationship to the process of storytelling or fiction writing. Not that I wanna fight somebody about this, but you have to at least admit that relationship exists, that they speak to each other and form and deform each other all the time. Even as a person who’s lived several decades, I would tell the story of my own life differently every decade. Where do we put that? What does that mean? Does that mean the truth shifts? Does that mean my memory shifts? Does that mean words on a page shift? I think that’s interesting. I think it’s worth holding open as a question and not shutting down with stern proclamations about what’s fiction and what’s nonfiction.

JR: I have another follow up question on smaller building blocks, on the word level. From a linguistic perspective, I’m so fascinated by how you play with language in a lot of your writing. I was noticing a lot of compound nouns like “lifedeath” from Chronology of Water, “warward” and “doomward” from The Book of Joan, and “motherwaters” from Thrust—just really beautiful language. Where is your inspiration for that? Where does that come from?

LY: First of all, thank you for noticing. It’s really important to me, but privately, because I don’t get asked that very often. So thank you. I just feel seen. I would have been a great linguist. I don’t just love language. I love the way languages interact. Different languages. And again, I’m including non-human languages.

So I’m obsessed with the possibility that the ways we use what we consider our own language are kind of stunted, and there’s some future world where language languages open up to each other and become more fluid. And they do in some cultures. I mean those words I’m making up? That’s a practice of certain languages and not other languages. More than one kind of Indigenous language tends toward the written and the visual having mergings, which you can study if you’re a linguist. I should have either been a linguist or a librarian.

It’s the interaction between languages that fascinates me. And so I mean that in terms of discourses too, like the way fairytales and science can weave, or the way math and music can interweave. That’s my obsession. That’s where that comes from. So when I make those words, I’m delighting in the ways in which language can be loosened from its hard-core uses and put into play with other languages and other altered states, other kinds of sounds and senses.

PH: Because you mentioned research and languages, I wanted to talk about researching heritage. I’ve noticed in The Small Backs of Children and Thrust, your girl protagonists seem to be informed by your Lithuanian heritage, and I wonder if you could speak to the process of researching your own ancestry, and how you incorporate that into your writing, especially given your ancestors come from a place of frequently dissolving and rearranging borders, and how that impacts your research.

LY: Totally. Lithuania is such a fascinating space of shifting meanings. So you called it, there. Maybe this is true of all our so-called histories: there’s what you can go collect, and there’s what’s lost to you forever. And in some ways that’s that same relationship between nonfiction and fiction.

I wrote a different novel called The Small Backs of Children that was based on a box I received of artifacts from my Lithuanian family history, and the whole novel is built around shit I found in this box. I would have an article about my great uncle who took some photographs of a Russian massacre of people at a hospital, and then he was sent to Siberia for a long time. I would have an article about that that was full-blown redacted. So that’s an example of a thing where you have the story and you can collect it, but the redacted version is the best you’re going to get, because it doesn’t exist anymore. And so what do you do to tell that story? How do you get to the truth of that story if all you have are pieces, artifacts, stories from other people that may or may not be real? Instead of going, “Oh, I can’t tell it,” I’m the kind of writer that’s like, “Oh, that’s a novel.” That’s why the novel is perfect, because the pieces you can collect and the pieces you’ll never know are where characters get born and where their drives get born, and where you can put language in close proximity to bodies and play. My relationship to research is as someone who delights in the artifacts of history as if they’re something you can use to make art. I don’t have a strong allegiance to one person’s version of history over another’s because I happen to know the versions of history we’ve tended to receive come from the people who had power. Which is why I love so much writing about nobodies or people who were made invisible, and not the heroes, because their stories would be different.

I spent 3 years just looking up our family’s original name, and then following all these people who probably have nothing to do with me but just the name, it was its own signifier, like a floating signifier. Which, by the way, the main character in Thrust, this Laisvè character—which means freedom in Lithuanian—she’s meant to be a floating signifier way more than she’s meant to be a human character in a traditional sense. She’s supposed to move around in time and space like a word could. So there’s the key to the whole story for you.

PH: Yeah, you call her a “carrier.” But in that way, language is also a carrier.

LY: Yeah, exactly, that’s why.

PH: I love that response. So I know you’re interested in brain science. We know from brain science that the flow experienced by artists, athletes, and craftspeople is similar. And you said that when you’re inside writing, you don’t want to be anywhere else, and I couldn’t help but hear a swimming metaphor in that. That language, water, and writing is the act of flow like swimming, and it’s meditative and spiritual and corporeal, but metaphysical at the same time. So, aside from being the skills that you’re best at—that I know of—how are writing and swimming like each other to you, if at all?

LY: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. One hundred percent. These categories didn’t exist when I was growing up, but I’m definitely a non neuronormative person, and so being in the regular world is incredibly hard for me to regulate. When I’m immersed in water, you know, think about it: it fills your nose and your eyes and your ears, and you float if you don’t move, if you just immerse in the water. And for some people that’s a scary state. For me, it’s like the pre-linguistic state, the amniotic state of womb. We all come from that water world whether we want to talk about it or not. And for me it’s like a direct prelinguistic, amniotic space. And water itself for me, the ocean, is a really great metaphor for the vast expanse of the subconscious and the imagination. And that’s where art making comes from.

Language is my medium because I’m a writer. And if I think of language as oceanic—like the imagination or like outer space, this vast, fluid, unknowable realm—then writing makes sense to me. For me, they’re almost inseparable. My understanding of being in water and my understanding of being in the imagination and writing stories, they’re almost the same thing to me. But I know that not everybody feels that. I understand. The point isn’t that everyone should feel what I feel. The point is, go in your life and find what feels that way to you and interrogate the relationship. So for me, it was the relationship between water and the imagination. I don’t know what it is for either of you, because I’ve never met you before, but something in your life corresponds to the way your imagination works and how you understand your art making, and it’s good to cultivate your understanding of whatever those things are.

JR: In The Small Backs of Children, you make a case for the importance of artists, as flawed as they might be, trying to make a difference in the world. How has your view of the role of artists evolved since you wrote that book, especially now in light of the pandemic and climate change and all of the other catastrophes that we’re dealing with?

LY: It’s just such an act of hubris to think that any of us can change the world. So I don’t think artists change the world exactly. I think we take turns so that the energy of giving a shit doesn’t die out. And so I’m alive during the time I’m alive. That means it’s my turn to keep the story pilot light lit. And it doesn’t matter if my one life changes the world. It matters that I keep the storytelling field alive when it came by and it was my turn. And then it’s your turn, which is why I said we need you. And maybe you’ll become famous and rich and singular, and that’s cool, it’s not like I don’t like those people. And maybe one of you will change the world. But for me personally, that isn’t the most important effort. The most important effort is to keep storytelling alive as an actual energy, so that the next people coming can keep change possible.

In The Small Backs of Children, those “artists”—and it’s okay to say they’re freakish, there’s something wrong with all of them, they’re terrible, they’re me and my friends, they’re just awful people—but they’re all trying to keep that: giving a shit. And this was my time, and this was my turn, and I’m trying to hold [storytelling] until it’s the next person’s turn to hold it. And it doesn’t have to be right or correct, it just has to be kept alive.

What they run into in that novel, besides, geopolitics, is commerce. The market. And my whole writing life, something that has not changed very much is, the the market makes me itchy and irritable. I think the relationship between art and capitalism is one that should stay itchy. Because when capitalism subsumes artmaking, our chance to hold the give-a-shit energy gets wobbly and gets subsumed by money.

JR: I actually tracked down your lit mag that you made with your partner, Andy. Northwest Edge, 2005. It amazes me because it makes CutBank looks so small and puny in comparison.

LY: Oh, no, no, no, no.

JR: I mean in terms of length.

LY: Oh yeah, it’s a big one.

JR: It’s impressive. So I would love to know, what was that experience of having a lit mag like for you? What did you learn from that experience of producing and editing it? And what advice would you have for editors of today?

LY: “Totally keep doing it” is the advice I have. We need it now more than ever. But the first zine I embarked upon was called Two Girls Review in Eugene, Oregon, and it was a really irreverent, much thinner, do-it-by-the-seat-of-your-pants, desktop publishing. Like, we were making them at Kinko’s. And then at some point we graduated to an actual printer. So they were perfect-bound and they looked pretty snazzy. Our whole goal was to put famous people like Yusef Komunyakaa next to an unknown person who wrote graffiti poems by the railroad tracks and put those kinds of authors next to each other. And it was so much fun. And it was the garage band philosophy or mentality.

And so by the time I got to Northwest Review, that was like three publications later. So the origin story is kind of the garage-band effort. As I shifted and changed what we were working on, I think the only difference is asking the question, how do you want your publication project to be in conversation in the world, and with whom? And if you can kind of bloom that energy, it’ll vibrate in a great way. And if you’re not exploring that question, it would be something to work on, because you can’t speak to everyone everywhere all the time. Even as a writer, [in] your own books, at some point, you have to admit who you want to be talking to and try to get that vibrating feeling.

So my advice would be, What is it you want to say? What’s the heart of the matter? And what conversation do you want to be part of? And then jump hard and fast.

JR: I want to talk about your Ted talk, The Beauty of Being a Misfit. You mentioned the misfit’s story “deserves to be heard, because you, you rare and phenomenal misfit, you new species, are the only one in the room who can tell the story the way only you would - and I’d be listening.” We’re curious, which stories in particular have you been listening to the most, and what made them stand out to you?

LY: There was a book that came out from that Ted Talk called The Misfit’s Manifesto, and the people I gathered to be in that book to tell their misfit stories were, for the most part, people who are often marginalized or in the pocket or made invisible. And my attraction to people who aren’t in the spotlight or who are in the periphery or to the side or the back in a room, is that they hold so much, while the people who get the attention amplify themselves so much. And I’m endlessly interested in what’s being held while the loudest story gets all the oxygen.

I’m even more interested in that than I’ve ever been because we’ve grown this bizarro, let’s just say America for now, American culture, where the loudest and biggest and celebratized gets all the airtime and oxygen, and nothing about that story reflects the rest of us. Nothing. If I could, in every room I enter, I’m most interested in the quietest people, the people who look a little off or sound a little off, or say nothing. I’m always interested in the person who maybe even is outside the door cleaning the floor or the person making the food, so that the people getting the attention have sustenance. So workers, laborers, people on the sides, in the periphery—I actually believe if there’s a story of humans, those are the people carrying it. I don’t think it’s the loudest people who get the most attention that are carrying the human story. Which is weird, because that’s what we’ve prioritized.

PH: I can see again how Thrust does a good job of trying to see them.

LY: See, it does have a storyline! There’s even almost a plot. Almost.

PH: I’m curious what you’re most fascinated in now. In all your work, we see a lot of the same motifs and themes emerge. In The Small Backs of Children, your character, the writer, says, “Inside of everything I have ever written, there is a girl. Sometimes she is dead and haunts the story like a ghost. Sometimes, she is an orphan of war. Sometimes, she is just wandering…. Sometimes I think I am following her into another place, or self.” We’ve seen young girls, water, abuse, dystopia, climate, the body and pleasure and pain and disfigurement as those recurring fascinations. What are you currently fascinated in? And what are you exploring in your latest writing?

LY: Yeah, that’s a great question. And yeah, I’ve tracked that girl, too. Obviously, she shows up a lot. And I think you guys know I had a baby girl who died. So that’s both literal and metaphoric, but I am feeling some shifting going on. For one thing, in Thrust, there was also a boy—and granted he was kind of weird—but it was an important figure to me that this boy emerged. I have a son who’s a young man now, so my life and my concerns are shifting. But what else is shifting is that I’m not as focused on the human story being the most important story, and Thrust was sort of showing me that. It’s filled with human characters, but that’s not all it’s filled with. And I’m interested in how shifting definitions of existence or humanity might include everything we’re made of, and where we come from in terms of our kind of molecular makeup and elements of space. And so I’m interested in existence that opens up what we mean by humans. So I’m going to have to keep pushing on what we mean by character and plot, if that’s the case, because sci-fi can only take you so far exploring what’s beyond human or what’s alien or what kind of weird character can you make? I actually want to know what happens next in terms of storytelling. So that sounds really vague and abstract, and I don’t have some great idea about it yet. I guess where I’m at right now is I’m kind of uninterested in the ways in which we’ve told stories and I’m kind of excited and interested in, What might story do if it underwent adaptation?

PH: I’m curious about warfare and discourse and language. We talk about war, which is the subject of your PhD, war literature. And lately I’ve been seeing this popular discourse, especially online, around warfare from multiple sides of a conflict saying, “You’ve lost the plot.” Since your PhD Is concerned with the narrative of warfare and metanarrative and binaries and breaking those binaries down, I wonder if you could speak to what you think that slang, maybe, is saying about our culture of storytelling and war and meaning making?

LY: Yeah, that’s huge, because I’ve spent my life thinking about that. And I’m going to continue to spend my life thinking about that. It does seem profoundly important to notice the activity of war and the forms that come out of the activity of work, like winners and losers. War is based on a model of “agon,” and so is conflict in prose writing: if you don’t have protagonists and antagonists, then you’re not doing storytelling. And [this concept] isn’t true.

What’s true is we’ve let this warring bellicosity between people dominate the forms we use to make art. And so there are legions of writers and artists and philosophers in every epoch who keep making the argument over and over again: that’s a really brutal model, y’all should stop that.

And so this is where I come back to that fundamental principle I have that we have to take our turns resisting. And it might not look like you won in your lifetime. It won’t look like that in my lifetime, but that’s not what’s important. What was important is, I took my turn so that the possibility still exists for whoever’s coming next, and it might happen in their lifetime. So you kind of have to give up the notion that your life is more important than anyone else’s and embrace the notion that well, fuck yeah, I got a life I’m taking my turn so that whoever’s next can have a turn, too.

JR: Such a great place to end on.

PH: I’m so honored to get to share this hour with you. Thank you so much. Is there anything else you wanted to share with us?

LY: The honor is totally mine. I love talking to writers and artists who are coming next. Because you’re it. You’re the vanguard. You’re what’s next. And so mostly I just want to say, thank you for choosing to do what you’re doing, because you’re what’s next, and it’s worth it. And I’m so thrilled for you. And whatever it is you end up creating, it was worth it. And there’s somebody ahead of you, and there’s going to be people coming next. So do what you can while you’re here.

PH: Thank you for being so generous with your time and your insights today. It’s been a delight.

LY: For me, too.