CUTBANK INTERVIEWS: A Conversation between Sara Batkie and Emily Collins

March 17, 2021

By Emily Collins

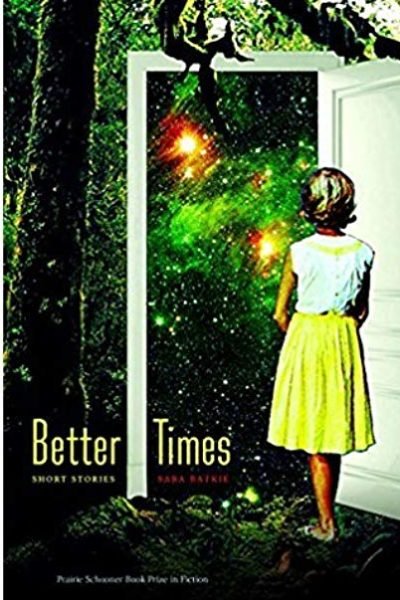

Sara Batkie’s collection, Better Times (Winner of the 2017 Prairie Schooner Book Prize) explores the overlooked lives of women and girls navigating lonely, uncertain worlds. In these stories, we meet characters who surrender to the darker circumstances of their lives without promise of hope or resolution. Though shackled by time and circumstances, Batkie’s characters reveal an unparalleled strength that helps them navigate the pain and uncertainty so expertly realized in these stories. Batkie’s writing is elegant, crisp and fearless in its exploration of trauma and intimacy.

Emily Collins: Your collection Better Times often reads like an interrogation of the phrase itself, particularly in relation to the lives of women and girls. I love how you explore the interior worlds of women past, present, and future in beautiful but unflinching prose. Their anger and repression felt very palpable to me. I'm curious to hear what aspects of women's lives you most felt called to write about for this collection?

Sara Batkie: Like many writers who went through an M.F.A. program, I was first drawn to short fiction because it was the most conducive to the workshop process. But I also found it to be an excellent medium for exploring a crisis removed from the necessities of strict plotting that the novel requires. What I mean by that is that I feel I’m often drawn to characters who are experiencing momentous shifts in their lives, but they’ll likely only recognize them as significant in hindsight. Thus, many of the great realizations the characters come to are happening outside the text itself. It is too much for the young narrator of “Laika” to actually identify that a fellow ward in a home for wayward girls is being molested by her brother, for example, nor will there ever be a satisfactory resolution to why Louisa gives birth to eggs in “Lookaftering.” Short fiction is the realm of intimation and mystery, often to the consternation of more mainstream readers who want resolution. I want to write about women who are angry, repressed, confused, and stymied by their times and circumstances while leaving open the possibility that these are emotions and experiences they might not get over. The suggestion that they will carry what’s happened to them around for the rest of their lives isn’t comforting, but I like discomfort. That’s when you learn what real character is.

EC: A number of your stories have calamitous openings. I think of Maude in "The Catastrophists" and Anya in "Foreigners." As a fiction writer, how do you navigate narrative tension and characterization when a story begins with sudden or gradual demise?

SB: I think that’s just the nature of the medium – I don’t know who said it first, but whenever I write I try to keep in mind the adage that you should start a story as close to the end as possible. There’s a lot less space to convey what you need to a reader than you’d have with a novel and it’s important to recognize both the freedoms and constrictions of those limits. That’s not to say every short story needs to begin with a bang, so to speak. But backstory and world-building are often elements that can be seeded in later as necessary rather than dumped at the start, and it also may take a few drafts before you realize what the right “end” is. I’ve often found that tension also arises naturally from characterization itself: by placing your characters in difficult situations and seeing how they react and surprise you. All of these things are in conversation with each other from the beginning, but our job as writers is to work out the right rhythm of it as we go along.

Sara Batkie is the author of the story collection Better Times, which won the 2017 Prairie Schooner Prize and is now available from University of Nebraska Press. She received her MFA in Fiction from New York University in 2010. Her stories have been published in various journals, received Notable Story citations in the 2011 and 2019 Best American Short Stories anthologies, and honored with a 2017 Pushcart Prize. Born in Bellevue, Washington and raised mostly in Iowa, Sara currently lives in Chicago, Illinois.

Find her at https://sarabatkie.com/

EC: Many of your characters, though lonely and dissatisfied, choose isolation in nuanced ways. I think of the father character in "When Her Father Was an Island." A Japanese soldier continues to defend an island long after WWII has ended and his daughter Maemi must learn to live a life without him. Yet his absence seeps into every aspect of her daily life. Have you always been interested in writing about trauma and intimacy in your fiction, or did the characters in Better Times slowly reveal these themes to you?

Emily Collins is the Interviews Editor for CutBank and a MFA in fiction candidate at the University of Montana. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in New Orleans Review, The Florida Review, The Atticus Review, The South Carolina Review, and others. She’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and other anthologies. When she’s not interviewing incredible writers, she enjoys hiking and volunteering.

SB: One of the most delightful and sustaining things about the writing life is to hear about the different ways that readers interpret your own work. The earliest story I wrote that ended up in the collection was drafted back in 2007, so roughly nine years before I submitted it for the Prairie Schooner Prize. It wasn’t until I started putting them all together that I began teasing out their commonalities and connections, which I mostly had to do because I had to start thinking about how to market it. So, I suppose I’ve always been interested in trauma and intimacy, having had varying levels of experience with both, but it wouldn’t feel right to say that I planned to write about either of those things. Allen Ginsberg said, “To gain your own voice, you have to forget having heard it,” and I think that applies to our thematic obsessions as well. All of our experiences and emotions and prejudices often inform the characters we write, even if they’re people who are very unlike us in many ways, as Maemi and her father are to me. But the real magic comes when we manage to forget that they’re ours and we see them anew through other eyes.

EC: I love how your short fiction captures historical moments in original ways. In "No Man's Land," we get family drama in the midst of the Gulf War. What inspired you to write about this distinct and somewhat neglected moment in history?

SB: I like that word: “neglected.” I find those corners of time to be the most useful and interesting, both as a writer and reader. For one thing, they’re underexplored which means there’s more room for play and experimentation. There’s a greater sense of discovery, too. You’re possibly writing about something that hardly anyone knows about yet, or “bringing the news” as one of my old professors put it. I always say that I’m more interested in the wives or daughters of the so-called great men of history than the men themselves, the people on the periphery whose opinions of those men and that history aren’t as well documented. There are enough doorstopper biographies about presidents and world leaders out there. When looking at the past, our lenses shouldn’t be so narrow. With the Gulf War in particular I was about the age of the younger sister, Addie, when that was going on. I remember seeing images of it on the news and being frightened by them, but it was also something happening far away. I only recognized the impacts of it when I was much older, and even then it’s not something that truly touched me personally. I didn’t know anyone who fought in it. But I feel like that’s often how we experience great upheavals, especially in America where isolationism and partisanship feel so prevalent in our culture, particularly now. Fiction is a way to re-experience those historical moments collectively through the eyes of an individual, and that’s part of its great power and responsibility.

EC: There are so many women short story writers I admire. I'd say many of them are masters of the craft. I'd love to hear of any women short story writers who have been a resource and inspiration for you. Are you working on a new collection of short stories or are you exploring the longer form as well?

SB: Absolutely! I was introduced to the stories of Lorrie Moore in college and the bladelike balance between comedy and tragedy in her work has always stuck with me. Stephanie Vaughn is another great, underappreciated writer. She’s only published one book, I believe, called Sweet Talk, but it’s a masterpiece. These days I don’t think there’s a better short story writer in the game than Danielle Evans, who just released her second book The Office of Historical Corrections late last year. She is constantly interrogating whose stories are allowed to be told and how in America in such artful and startling ways. I find her very inspiring. I have been working on some projects, if somewhat sporadically. Like most writers I know, I’ve struggled with how creative endeavors fit into my pandemic-bound life. I’m more often firing up a streaming service than a Word doc. But I have managed to complete a novel draft that some friends are looking at, and I’m happy to be in the “wait and see” stage of that rather than the “is this anything?” stage.