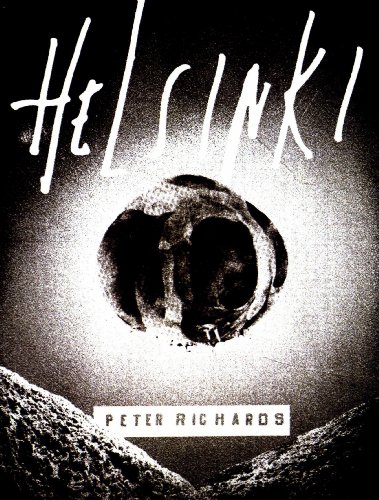

Action Books, 2011. Reviewed by Brett DeFries Most reviewers can and rightly will note Peter Richards' close affinity with central and eastern Europe, particularly contemporary Slovenian superstars Tomaz Salamun and Ales Steger. But one could also include Vallejo on that list, or Bolivian poet Jaime Saenz, the way horror floats into scriptural heights; or O'hara and his spontaneity, his exuberant grief; or second generation New York School poet Joseph Ceravolo's trust in major spills; or fringe surrealists like Char or Cesaire; or others. None of these would be quite wrong, but none of them would be quite right either. Like his previous two collections, OUBLIETTE and NUDE SIREN, HELSINKI's verbal range and span of influence are seemingly endless, but HELSINKI absorbs influence so completely into its fat and muscle and bones, that no one ancestor is separate from the others, and all of them are confused. One might even imagine Whitman1, on his way to swallowing everything, getting Dickinson2 caught in his throat:

Most reviewers can and rightly will note Peter Richards' close affinity with central and eastern Europe, particularly contemporary Slovenian superstars Tomaz Salamun and Ales Steger. But one could also include Vallejo on that list, or Bolivian poet Jaime Saenz, the way horror floats into scriptural heights; or O'hara and his spontaneity, his exuberant grief; or second generation New York School poet Joseph Ceravolo's trust in major spills; or fringe surrealists like Char or Cesaire; or others. None of these would be quite wrong, but none of them would be quite right either. Like his previous two collections, OUBLIETTE and NUDE SIREN, HELSINKI's verbal range and span of influence are seemingly endless, but HELSINKI absorbs influence so completely into its fat and muscle and bones, that no one ancestor is separate from the others, and all of them are confused. One might even imagine Whitman1, on his way to swallowing everything, getting Dickinson2 caught in his throat:

Tonight Julia awakens painting the way our kiss can sound there's a reticent lilt to her hand as each hastened stroke gets confused with our own she's painting let the hallway worry about the hallway she's not painting sounds in a ship she's painting they began by walking the lawns together they began without emissaries they began to get specific so far they are just two smears so it's hard to tell if the hair was left to reference the painter or in fact just fell where the painting had seemed seems how we know how seems together with all forms hues and shades of leaf we fell there fallen and seeming last night went searching for three city blocks there is no city not even Helsinki has something to do with itself yet that banner deploring the length of our fingers as it would not burn bury nor tear at the fray begun by our teeth I spread it out and bloodied myself bled until the study can say the banner means nothing the banner means nothing but the banner remains

In these poems, all of them untitled, unnumbered, unpunctuated, a speaker earnestly and humanly explores the limit, not just of language, but of things themselves. I'd say that these poems have no ideas but in things, but with such a weakened distinction between the corporeal and the broadly phenomenal, Williams' famous dictum turns too vague to grow a pulse. Part of this confusion is the synaesthesia, which may be a blessing or a blessed syndrome, but is chronic either way within HELSINKI. If you can paint the sound of a kiss, then you can also call into question the meaning of a kiss and the limits of sight. But there is more to it. This doubting of banners and cities is not just a drug induced poetic positivism. No. In HELSINKI, the poem is the thing independent of science, and everything else is a thing in the mind of the poem. In a poem, the rules of experience change. Anywhere else, HELSINKI is no such place, and the banner means nothing.

One way I can think of to be simultaneously ecstatic and hidden inside oneself is to seriously CONTAIN the multitude like a covered birdcage whose bird is the multitude. Or to be a self scattered haplessly about:

I do remember as a small boy being brushed by a black man in the courtyard feeling the small of my back lightly brushed so that it sank deep into my imagination and partly the initial deathblow Helsinki prepared for my boyhood drawing an invisible orange line at the base of my skull leading to this villa my parents shared between them each room holding a portrait of one of my parts and one room wrongly represents the cyst in my knee another captures my chin before it was mended a third stretches to the evil side of the room where this tear sits hard and white and so I think it must be cold so cold the cold outnumbers ice from when the ice was young no tear has taken its place so it must live beyond the great doors of winter and sing as many flesh and blood songs as a frozen tear can sing.

The line down his skull leads to his parent's house, the rooms of which contain inaccurate sketches of his parts. Finally, in the evil side of a room, a frozen tear lives "beyond the great doors of winter," and the tear sings. What he finds inside himself is both his self in parts and that which lives outside.

For all its lyrical wanderings, though, HELSINKI remains a strongly narrative series with recurring characters, locations, and a quest perduring across the void of death. Too, there are important narrative turns, mostly around Julia's shifting axis. Julia, the colonized one, the monolith, the green bee-like horse with a swinging herrick. Julia, whose chariot the speaker would never dare take, because "it might change Julia / into an island capable of holding / as many ships as she can / until she herself is the island's / freed ringlet of ships." Much of Julia's shapeshifting, I think, owes to HELSINKI's superb attention to detail. As the eye moves, the image changes, and if a decent view of a villa is as much worth our attention as disappearing soldiers, then there is a great deal of change. Amidst that change, every seen object is an object seen in fervor.

Consider this passage from Motherwell's 1970 statement before the United States Congress:

As an artist, I am used to being regarded as a somewhat eccentric maker of refined, but rather unintelligible, objects of perception. Actually, those objects contain a murderous rage, in black and white forms, of what passes for the business of everyday life, a life so dehumanized, so atrophied in its responsibility that it cannot even recognize a statement as subtle and complicated as the human spirit it is meant to represent. I am as well, at other times, an expresser of adoration for the miracle of a world that has colors, meaningful shapes, as spaces that may exhibit the real expansion of the human spirit, as it moves and has its being.

Romanticism aside, what interests me here is the notion of painter as finder of monads. That is, someone with attentions so acute that objects divide until qualities become their own indivisible units of perception. And divorced of unity, these new units grow rather unintelligible. If HELSINKI is in fact a place, it is a place like drains "where the hemispheres / do war and the hemispheres unite." The units split and collide so quickly that the speaker is left to explore, with each event, every scenario of possible feeling. In the same poem as the hemispheres, a handsome older man pulls the speaker's face off by the braid, tells him to "shut the fuck up," and seems to want the speaker to "serenely drink from [his] back." But in a sudden turn, the poem ends: "with that we both had / a good laugh and you should have been with us / that day when we all went sledding together / down a great monster of sunlight and hair."

Even more than Motherwell, and as much as any poetic influence, I see Francis Bacon in these poems. In Bacon's painting, Triptych August 1972, each panel, side by side, contains a figure resembling, in various degrees of rudeness, a human form. Behind each figure is a black rectangle like a wide threshold or vertical grave, and beneath each figure is a puddle, spilling from some unraveling place on the figure. In the center panel, the puddle is

pure lilac, and the figure is more lump than human. Also, the central figure is in repose. In the two side panels, the puddle is a mix of lilac and the color of skin. The side figures sit in a chair, though sections of torso are absent. Instead, where the torso should be, there is the void of the threshold behind them.

pure lilac, and the figure is more lump than human. Also, the central figure is in repose. In the two side panels, the puddle is a mix of lilac and the color of skin. The side figures sit in a chair, though sections of torso are absent. Instead, where the torso should be, there is the void of the threshold behind them.

In Helsinki, an oarsmen rolls a cigarette and stands, but his waist is enchanted.

In a 1971 interview, Bacon says, "death is the shadow of life, and the more one is obsessed with life, the more one is obsessed with death." Further exploring this twinness, art critic Lorenza Trucchi remarks, "when death appears as a stark and hermetic inevitability, no further barrier can remain between these two parallel obsessions that finally meet in the infinity of 'nothingness.'" In HELSINKI, FINALLY is NOW, and in keeping with Trucchi, "there is no city / not even Helsinki has something to do with itself." But like Bacon's Triptych, a vision remains—terrible, playful, dead, and alive:

I have these competing transparent patches ingesting my body help me I'm growing quilted all I can see is the yard with its animals and a tunnel filling my chest

******

1Throwing myself on the sand, confronting the waves, I, chanter of pains and joys, uniter of here and hereafter, Taking all hints to use them, but swiftly leaping beyond them, A reminiscence sing. (Whitman)

2And then a Plank in Reason, broke, And I dropped down, and down— And hit a World, at every plunge, And Finished knowing—then— (Dickinson)

******

PETER RICHARDS was born in 1967 in Urbana, Illinois. He is a recipient of a Massachusetts Cultural Council Grant in Poetry, an Iowa Arts Fellowship, an Academy of American Poets Prize, and the John Logan Award. His poems have appeared in Agni, Colorado Review, DENVER QUARTERLY, FENCE, The Yale Review, and other journals. He is the author of OUBLIETTE (Verse Press/Wave Books, 2001), which won the Massachusetts Center for the Book Honors Award; NUDE SIREN (Verse Press/Wave Books, 2003); and HELSINKI (Action Books, 2011). The University of Montana-Missoula's visiting Hugo Poet Spring Semester 2011, Richards has taught at Harvard University, Tufts University, and Museum School of Fine Arts, Boston.

BRETT DEFRIES received an MFA from the University of Montana, where he received an Academy of American Poets Prize. His work has appeared in or is forthcoming from Colorado Review, Eleven Eleven, Laurel Review, Devils Lake, New Orleans Review, Phoebe, and elsewhere.