A review of Lions, Remonstrance by Shelly Taylor (Coconut Books, 2014)

--by Henrietta Goodman

Shelly Taylor is a poet from the South, as I am. This was all I knew about her when one of CutBank’s editors gave me a copy of Lions, Remonstrance and said “I think you’ll like it.” I wondered whether a presumption of Southern kinship might have led to this belief, never mind the fact that unlike Taylor, who clearly cherishes her Georgia roots, I got the hell out of North Carolina twenty-five years ago and almost never go back. As I began reading, I felt a sort of poetic culture-shock, or rather, form-shock: the book is nearly a hundred pages long and the poems are untitled, their language full of leaps, swerves, and gaps, as in the opening lines of the third poem:

I realized the sea the day I got here was to some people the way

it came right toward me nurse-handed, at the door

with a bushel, white picket teeth the lines, the dunes a watercolor

mother for the upstairs bedroom, someone to hold my hand

not full of disaster as in sharp teeth that hunt of night lions. I leaned in

the skyline ramparts seize charlie horse up made myself get

outside daylight like man is a common ruin, mark my word…

Whose voice was this? The primary speaker of Lions, Remonstrance is the lover of a soldier home from war, Penelope to an Odysseus returned but damaged—alcoholic, violent, possibly suicidal. But the soldier’s voice and experience enter as well, blurring the boundaries between self and other, between the conventionally feminine and masculine realms, so even in the seemingly innocuous act of sewing, the speaker notes: “…A dress made on / a Singer the bullet tempo…”

The confidence in self and reader the book’s language contains made me feel, initially, insecure and a bit envious. Taylor’s stylistic choices are not ones I feel comfortable making in my own work, and I couldn’t help but start tallying up the similarities and differences between her book and my current project, also a book-length memoir-based sequence, but written in linked Italian sonnets: the formal opposite of her work. (I worry about the clarity of my pronouns. I worry about being “understood.”) But when I reached the point when the speaker of Lions, Remonstrance leaves her lover, an act of self-preservation which haunts the second and third of the book’s three sections, I stopped looking for differences. I have made—am making—a similar departure, so I know well the anger and loss in the lines that end the book’s penultimate poem:

in my dream, my very dream I was of course a child but not really;

I threw my food on the floor & hit repeatedly the man at the table

still composed; he said how often does this happen, I said

my whole life, it happens my whole life through.

The more I read, the more I began to view the book’s shifting pronouns and verb tense, its surprising and often fragmented syntax, as less a barrier to understanding and more an opening: a gift of intimacy and a kind of permission.

One of the most powerful poems, from the approximate mid-point of section two, intertwines scenes from Afghanistan with the world “back home,” where “the town sits down on his chest making breathing trifling.” Early in the poem we are told: “A dog carries a human hand across the sand, you cannot have it, she is a bitch / feeds it to her litter tucked under the edge of a house side…” The poem’s closing lines return to this scene, juxtaposing violence and tenderness, destrudo and libido:

…You blew the dog & her puppies with a hand grenade—they cannot

eat flesh your dog I called Bee, threw the ball for him nightly. It natures

toward the noose. Uncle Jim knows as does Yesenin David Foster Wallace.

I would’ve done anything: Waffle House at 8am 6-hour drive to Vegas I have

white dresses, be a good shotgun my head on his lap, his fingers on my temple.

In an interview with Kristen Nelson for Trickhouse, Taylor says, “Just because you might’ve made sense of a thing by writing on it for four years doesn’t mean the thing will stop its screaming. I guess nothing changes but is finally understood.” This is the remonstrance—the protest—the book makes: not just against the destructive impact of war on soldiers and those who love them, but against the inability of poetry, of language, to rectify the past. In the same interview, Taylor cites the words of Günter Grass: “Only what is entirely lost demands to be endlessly named: there is a mania to call the lost thing until it returns.” As writers, we can use the sources of our pain as material, and thus gain a sense of control over the creation of art, but the art we create can never fully compensate for the loss of which it is built. Lions, Remonstrance enacts this awareness. In these poems, you will encounter a pain not different from your own, and so these poems will hurt you. Let them.

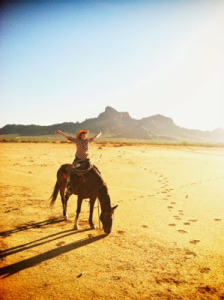

Shelly Taylor is the author of two full-length collections: Lions, Remonstrance (Coconut Books Braddock Book Prize: 2014) & Black-Eyed Heifer (Tarpaulin Sky: 2010), as well as three chapbooks: Peaches the yes-girl (Portable Press at YoYo Labs: 2008), Land Wide to Get a Hold Lost In (Dancing Girl: 2009), Dirt City Lions (Horse Less: 2012). Hick Poetics, an anthology of contemporary American rural poetry co-edited with Abraham Smith, will be released from Lost Roads Press in early 2015. Born in deep south Georgia, Taylor is an instructor at the University of Arizona. She calls Tucson & horseback home.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the author:

Shelly Taylor is the author of two full-length collections: Lions, Remonstrance (Coconut Books Braddock Book Prize: 2014) & Black-Eyed Heifer (Tarpaulin Sky: 2010), as well as three chapbooks: Peaches the yes-girl (Portable Press at YoYo Labs: 2008), Land Wide to Get a Hold Lost In (Dancing Girl: 2009), Dirt City Lions (Horse Less: 2012). Hick Poetics, an anthology of contemporary American rural poetry co-edited with Abraham Smith, will be released from Lost Roads Press in early 2015. Born in deep south Georgia, Taylor is an instructor at the University of Arizona. She calls Tucson & horseback home.

About the interviewer:

Henrietta Goodman is the author of two books of poetry, Take What You Want (winner of the 2006 Beatrice Hawley Award from Alice James Books) and Hungry Moon (Mountain West Poetry Series, 2013). Her poems have recently appeared in New England Review, Massachusetts Review, Guernica, and other journals. She teaches part-time in UM’s English department, and is co-director of Missoula’s Open Country Reading Series.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------