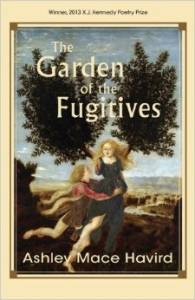

The Garden of the Fugitives by Ashley Mace Havird

Reviewed by Scott Brennan

The Garden of the Fugitives, Ashley Mace Havird's poetic examination of women in a male chauvinist society, doesn't shove "the boot in face" like Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” does; instead, Ms. Havird shows us the jagged edges of the princess's broken glass slippers.

In "The Lost Boys," the collection's opener, Eve, the first in a series of archetypal women, is portrayed as God’s gift to Adam. The irreverent poem (the speaker, presumably Satan, refers to the Lord God as "LG") serves as a sympathetic justification of Eve's actions. Though God and Adam "thought they held her spellbound," Eve bucks her unequal status by resorting to sabotage--tempting Adam to eat the apple, an action that initiates the Fall.

The portraits of men in the collection are generally unflattering and sometimes unsavory. Uncle Harry, the pedophile who fondles a girl in “Cleaning the Garage,” is ultra creepy when, as the adult female speaker recalls, he asked if she enjoyed the tickling sensation of being felt up. (Definitely no tickle, Uncle Harry.) We are morally verified when he gets what he deserves--a deadly heart attack--though chilled because the violation has hardened the speaker, causing her to “feel nothing at all.”

The imagery of rape (physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual) evolves into a troubling motif. In “Persephone’s Crown,” the girl in the Jaycee's pageant wears a crown that evokes Christ's crown of thorns. (The girl's crown, like Christ's and Persephone's, mocks the regality of its wearer.) The little girl, like Persephone, is forced to fulfill a public role she neither wants nor understands. Poems like these emphasize martyrdom, the way girls are taught to sacrifice individuality to satisfy societal expectations. Ms. Havird points out the cruel irony of women who are ostensibly made princesses and queens (implying respect and authority), but who in reality begin to fester when they awaken to realize they are being patronized.

Three of the most interesting poems in the collection are "Queen for a Day," “The Harvest,” and “Daughter, 14, with Scissors.” Each captures Ms. Havird's preoccupations: women crippled by a patriarchal society, the modern woman's kinship with women of the past (both actual and mythological), and the ways in which guilt erodes women's ability to empower themselves.

"Queen for a Day," as with "The Lost Boys" and "Persephone's Crown," depicts a powerless woman. Addressing her dead grandmother in a photograph, the speaker says, "You could be my father in drag," and later describes the grandmother's patent leather handbag, an object normally associated with the accoutrements of femininity, as a bludgeon. The grandmother possesses masculine qualities, but she has repressed them, and the speaker detects the unhappiness that has resulted. She wants to imagine her grandmother as having been a strong, creative woman who "painted frescoes / on sunlit walls of Tuscan villas" or sang "hoarse blues between Dubonnets / in a dark Parisian cellar." The truth is the grandmother lived a mundane life, one spent in "a tolerable marriage." Havird emphasizes the ordinariness of the grandmother, especially when we learn she held a minor position, "a spot in the secretarial pool," a job that typifies the stifled, demeaning quality of her life. The speaker feels guilty because she never celebrated the grandmother's birthday, and she fantasizes about a party held in a retirement home in which she and the relatives might have made the grandmother a special "queen for a day." (The imagined celebration's rosy inflation of the grandmother's dull life amplifies the desolation of the fact the party never even took place.) The speaker continues to examine the photo (which serves as a mirror, for, as the speaker says, the grandmother's eyes "look like mine") and notes how forced the grandmother's smile is while she poses before an unidentified man (perhaps the grandfather) "whose shadow hulks / as he mounts the scoured / searing steps." "Mounts," with its blunt sexual connotations, seems a particularly telling word.

In "The Harvest," we see the speaker in an adventurous, empowering situation. The poem is set at a female friend's vacation home on a Caribbean island. The speaker, fascinated by the local flora, reads a field guide and while doing so identifies the exotic trees around her--a task that parallels Adam and Eve's naming of the plants and the animals. There is no Adam in this tropical Eden, through. Instead, there's the speaker's divorced friend who, as part of the settlement, lives in "the house she'd gotten to keep." The two women engage in catching conch (probably, given the geographic region, queen conch--subtly continuing the collection's motif). The speaker can't believe she is going to kill one for its shell, but the friend ("divorce has toughened her") shows her how: "one jab, a second, and the barb twisted through." The speaker says, "I can't believe I'm doing this," and the friend responds by saying, "You wanted it." The violent killing of the conch seems ritualistic, the sacrifice required of a rite of passage. The visceral experience and the sexually charged language reveal an emotionally invigorated speaker. In the end, the soft flesh of the marine snail is discarded to the scavengers who are "merciful and quick," and the beautiful, durable shell is retained. The divorced woman, represented by the shell, seems to offer an alternative to the less satisfactory, vulnerable life the speaker by implication appears to be living.

One of the most uneasy and best poems in the collection is "Daughter, 14, with Scissors." Here we see the speaker as the mother of an emotionally fragile child. The scissors, front and center, fill the poem with destructive potential energy. The speaker laments ironically that her "daughter still can't use scissors" after discovering the child's intentional, self-injurious cut around the wrist, which looks grotesquely like a bungled, homemade bracelet. The sense of failure in the poem intensifies when the child delivers the terrifying whisper, "I wish I was dead." Because the daughter's self-esteem has crumbled, the speaker yearns to "curl over her / as though to reclaim her with my body, reconnect / our pulses." Unable to facilitate the reconnection, the speaker concedes, "She's part of that world of Grimm / whose spindle will have its way; / the princess seduced to a sleeping wheel." This poem, like many in the collection, suggests women, because they are indoctrinated from childhood into a culture that cultivates female weakness, are ill-equipped to deal with adversity. The chronic frustration can lead to a deadened sense of self or even self-destruction.

Curiously, almost all the poems in the collection are written in the present tense. Viewed as an artistic statement, the present tense can mean the injustice is happening now, all the time. As a rhetorical strategy, I find the choice sometimes problematic, as in these lines from "At Stonewall": "I'm wading through a clearing, / knee-deep in khaki weeds and / coreopsis so yellow my eyes burn." The instant objectification of one's own experiences generally doesn't happen in real life. The poem becomes awkward because, to use a metaphor, it is asked to be not only the video camera, but also the video and the live commentary on the video, itself, as it is being made.

Though Ms. Havird quite often writes gorgeously (she possesses an extraordinary eye for detail and ear for language, not to mention sophistication of sensibility), she sometimes mixes levels of diction with uneven results. I don't respond well to her occasional use of the Southern colloquial, as in "Lunar Eclipse": "Hard drinking at the camp house. // Come dusk, we nudge each other / to the pond's edge." "Come dusk" seems like everyday speech teetering upon stilts. Later in the poem, though, Havird retunes when she writes: "The moon, diminished, / pale as a communion wafer, / rises."

The Garden of the Fugitives is a book rich with allusions, motifs and layered themes. Despite my quibbles with a few stylistic choices, the collection is cohesive and possesses an irresistible undercurrent. It strikes me as being an exceptional first full-length collection. The portraits of girls, women, wives, and mothers are powerful in their smoldering epiphanies.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the author:

Ashley Mace Havird has published three books of poems: The Garden of the Fugitives (Texas Review Press, 2014), which won the 2013 X. J. Kennedy Prize, Sleeping with Animals (Yellow Flag Press, 2014) and Dirt Eaters (Stepping Stones Press,2009),which won the 2008 South Carolina Poetry Initiative Prize. Her poems have appeared in such journals as Shenandoah, The Southern Review, Southern Humanities Review, Southern Poetry Review, Tar River Poetry, and The Texas Review. Her short stories have appeared in The Virginia Quarterly Review and elsewhere. She has also completed a historical novel for advanced middle-grade readers and older, An Old Horse Named Troy, which placed first in the children's literature category of the 2014 Leapfrog Press Fiction Contest. A recipient of a Louisiana Division of the Arts Fellowship in Literature, she lives in Shreveport, Louisiana, with her husband, the poet David Havird, and their own best dog in the world.

About the reviewer:

Scott Brennan's poetry and reviews have appeared in a number of magazines, including Smithsonian, The Gettysburg Review, Harvard Review, Sewanee Review, The Carolina Quarterly, and elsewhere. He was selected by Billy Collins to receive the Scotti Merrill Award, and he was the 2014 runner-up for Rosebud's William Stafford Award, judged by Diane Wakowski.