"Rock’s very sensitive novel spotlights the purpose of faith [...] it also touches on something deeply pervasive and undoubtedly primeval."

"Rock’s very sensitive novel spotlights the purpose of faith [...] it also touches on something deeply pervasive and undoubtedly primeval."

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Lions, Remonstrance" by Shelly Taylor

A review of Lions, Remonstrance by Shelly Taylor (Coconut Books, 2014)

--by Henrietta Goodman

Shelly Taylor is a poet from the South, as I am. This was all I knew about her when one of CutBank’s editors gave me a copy of Lions, Remonstrance and said “I think you’ll like it.” I wondered whether a presumption of Southern kinship might have led to this belief, never mind the fact that unlike Taylor, who clearly cherishes her Georgia roots, I got the hell out of North Carolina twenty-five years ago and almost never go back. As I began reading, I felt a sort of poetic culture-shock, or rather, form-shock: the book is nearly a hundred pages long and the poems are untitled, their language full of leaps, swerves, and gaps, as in the opening lines of the third poem:

I realized the sea the day I got here was to some people the way

it came right toward me nurse-handed, at the door

with a bushel, white picket teeth the lines, the dunes a watercolor

mother for the upstairs bedroom, someone to hold my hand

not full of disaster as in sharp teeth that hunt of night lions. I leaned in

the skyline ramparts seize charlie horse up made myself get

outside daylight like man is a common ruin, mark my word…

Whose voice was this? The primary speaker of Lions, Remonstrance is the lover of a soldier home from war, Penelope to an Odysseus returned but damaged—alcoholic, violent, possibly suicidal. But the soldier’s voice and experience enter as well, blurring the boundaries between self and other, between the conventionally feminine and masculine realms, so even in the seemingly innocuous act of sewing, the speaker notes: “…A dress made on / a Singer the bullet tempo…”

The confidence in self and reader the book’s language contains made me feel, initially, insecure and a bit envious. Taylor’s stylistic choices are not ones I feel comfortable making in my own work, and I couldn’t help but start tallying up the similarities and differences between her book and my current project, also a book-length memoir-based sequence, but written in linked Italian sonnets: the formal opposite of her work. (I worry about the clarity of my pronouns. I worry about being “understood.”) But when I reached the point when the speaker of Lions, Remonstrance leaves her lover, an act of self-preservation which haunts the second and third of the book’s three sections, I stopped looking for differences. I have made—am making—a similar departure, so I know well the anger and loss in the lines that end the book’s penultimate poem:

in my dream, my very dream I was of course a child but not really;

I threw my food on the floor & hit repeatedly the man at the table

still composed; he said how often does this happen, I said

my whole life, it happens my whole life through.

The more I read, the more I began to view the book’s shifting pronouns and verb tense, its surprising and often fragmented syntax, as less a barrier to understanding and more an opening: a gift of intimacy and a kind of permission.

One of the most powerful poems, from the approximate mid-point of section two, intertwines scenes from Afghanistan with the world “back home,” where “the town sits down on his chest making breathing trifling.” Early in the poem we are told: “A dog carries a human hand across the sand, you cannot have it, she is a bitch / feeds it to her litter tucked under the edge of a house side…” The poem’s closing lines return to this scene, juxtaposing violence and tenderness, destrudo and libido:

…You blew the dog & her puppies with a hand grenade—they cannot

eat flesh your dog I called Bee, threw the ball for him nightly. It natures

toward the noose. Uncle Jim knows as does Yesenin David Foster Wallace.

I would’ve done anything: Waffle House at 8am 6-hour drive to Vegas I have

white dresses, be a good shotgun my head on his lap, his fingers on my temple.

In an interview with Kristen Nelson for Trickhouse, Taylor says, “Just because you might’ve made sense of a thing by writing on it for four years doesn’t mean the thing will stop its screaming. I guess nothing changes but is finally understood.” This is the remonstrance—the protest—the book makes: not just against the destructive impact of war on soldiers and those who love them, but against the inability of poetry, of language, to rectify the past. In the same interview, Taylor cites the words of Günter Grass: “Only what is entirely lost demands to be endlessly named: there is a mania to call the lost thing until it returns.” As writers, we can use the sources of our pain as material, and thus gain a sense of control over the creation of art, but the art we create can never fully compensate for the loss of which it is built. Lions, Remonstrance enacts this awareness. In these poems, you will encounter a pain not different from your own, and so these poems will hurt you. Let them.

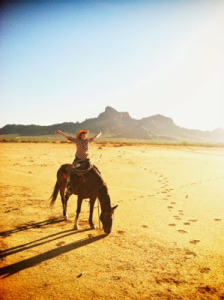

Shelly Taylor is the author of two full-length collections: Lions, Remonstrance (Coconut Books Braddock Book Prize: 2014) & Black-Eyed Heifer (Tarpaulin Sky: 2010), as well as three chapbooks: Peaches the yes-girl (Portable Press at YoYo Labs: 2008), Land Wide to Get a Hold Lost In (Dancing Girl: 2009), Dirt City Lions (Horse Less: 2012). Hick Poetics, an anthology of contemporary American rural poetry co-edited with Abraham Smith, will be released from Lost Roads Press in early 2015. Born in deep south Georgia, Taylor is an instructor at the University of Arizona. She calls Tucson & horseback home.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About the author:

Shelly Taylor is the author of two full-length collections: Lions, Remonstrance (Coconut Books Braddock Book Prize: 2014) & Black-Eyed Heifer (Tarpaulin Sky: 2010), as well as three chapbooks: Peaches the yes-girl (Portable Press at YoYo Labs: 2008), Land Wide to Get a Hold Lost In (Dancing Girl: 2009), Dirt City Lions (Horse Less: 2012). Hick Poetics, an anthology of contemporary American rural poetry co-edited with Abraham Smith, will be released from Lost Roads Press in early 2015. Born in deep south Georgia, Taylor is an instructor at the University of Arizona. She calls Tucson & horseback home.

About the interviewer:

Henrietta Goodman is the author of two books of poetry, Take What You Want (winner of the 2006 Beatrice Hawley Award from Alice James Books) and Hungry Moon (Mountain West Poetry Series, 2013). Her poems have recently appeared in New England Review, Massachusetts Review, Guernica, and other journals. She teaches part-time in UM’s English department, and is co-director of Missoula’s Open Country Reading Series.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Like a Beggar" by Ellen Bass

Like a Beggar by Ellen Bass

Copper Canyon Press, 2014

ISBN 978-1-55659-464-9

Paperback, 86pp., $16.00

Review by Carol Smallwood

The epigraph is by Rainer Maria Rilke: “But those dark, deadly, devastating ways, how do you bear them, suffer them? ---I praise.” It applies to the poems.

The new collection that I was waiting for since The Human Line (Copper Canyon Press, 2007), collection opens with the poem, “Relax” listing bad things that will most likely happen to you but ends with the lines:

Oh, taste how sweet and tart

the red juice is, how the tiny seeds

crunch between your teeth.

The 46 poems are not separated into parts like her last collection; the charcoal and oil cover art is also by Carolyn Watts and Copper Canyon Press again is the publisher.

Her strength as a poet in my view is her fearless look and acceptance as in “Morning” on the topic about her mother’s death:

Here long-exhaled breaths

kept coming against her

resolve. And in the exquisite

pauses in between

I could feel her settle—

the way an infant

grows heavier and heavier

in your arms

as it falls asleep.

Her very readable poems are mostly in a narrative style based on common events and places such as “Women Walking” but this commonality is wide as in “Another Story” that includes the television program NOVA and the size of the universe, Marlon Brando, red fingernails, and baby bats. “Pleasantville, New Jersey, 1955” includes an unlikely mix of T-shirts, A&P parking lots, deliverymen, a pack of Camels, Allen’s Shoe Store, tweed skirts, and ends with it all being “…at the center of our tiny solar system flung out on the edge of a minor arm, a spur of one spiraling galaxy, drenched in the light.”

Quite a few poems deal with aging but “Ode to Invisibility” concludes “It’s a grand time of life” and the element of sex is a often mentioned. While the immensity of the rings of Saturn and the Hubble Telescope are topics, so are the smallness of flies and wasps.

Bass describes the praise that a poet has for the onion in “Reading Neruda’s “Ode to the Onion”: “When he praises the onion, nothing else exists. like nothing else exists in the center of the onion. Like nothing else exists when you fall in love.”

My favorite is “When You Return” that begins:

Fallen leaves with climb back into trees.

Shards of the shattered vase will rise

and reassemble on the table.

Plastic raincoats will refold

into their flat envelopes.

Bass poems impact one depending on awareness at the time of reading. That is true of course of all poetry and writing but with Bass poems, you will see layers you didn’t catch before with other readings and they have a solid dissection of humanity. What looks effortless, requires much expertise to write, to make it universal. She also has the ability to surprise with such descriptions as high heels on linoleum “distinctive as the first notes of Beethoven’s Fifth” and I am already looking forward to her next collection.

------------------------------------------------------------------

About Ellen Bass:

Ellen Bass’s most recent book of poetry, Like a Beggar, was published in April 2014 by Copper Canyon Press. Her previous books include The Human Line (Copper Canyon Press), named a Notable Book by the San Francisco Chronicle and Mules of Love (BOA Editions) which won the Lambda Literary Award. She co-edited (with Florence Howe) the groundbreaking No More Masks! An Anthology of Poems by Women (Doubleday).

Her poems have appeared in hundreds of journals and anthologies, including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The American Poetry Review, The New Republic, The Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, and The Sun. She was awarded the Elliston Book Award for Poetry from the University of Cincinnati, Nimrod/Hardman’s Pablo Neruda Prize, The Missouri Review’s Larry Levis Award, the Greensboro Poetry Prize, the New Letters Poetry Prize, the Chautauqua Poetry Prize, a Pushcart Prize, and a Fellowship from the California Arts Council.

About Carol Smallwood:

Carol Smallwood’s over four dozen books include Women on Poetry: Writing, Revising, Publishing and Teaching, on Poets & Writers Magazine list of Best Books for Writers. Water, Earth, Air, Fire, and Picket Fences is a 2014 collection from Lamar University Press; Divining the Prime Meridian, is forthcoming from WordTech Editions.

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Any Anxious Body" by Chrissy Kolaya

Any Anxious Body by Chrissy Kolaya $18.00 | 83 pages | Broadstone Books, 2014

Review by Joshua Preston

A mother, daughter, and teacher, Chrissy Kolaya is an alumna of the Norman Mailer Writers Colony and her poems have been compared to those of the New York School. Her first book of poems, Any Anxious Body, joins together a passionate love of Frank O’Hara with a natural affinity for archival poetics. This is not a book of Lunch Poems; instead, it is a book of particular moments, captured words, the weaving of a narrative that is more than a day in the life. This collection has the remarkable ability of presenting whole lives through single days. It illustrates that sometimes the things one remembers says more about the recorder than the record.

Everyone who walks through these poems are learning the same lesson:

Her father tells her one night – I got news for you, kid.

You’re not getting off this planet alive.

Words

with which any anxious body

might find solace. (76)

This single revelation is what connects the sometimes-disparate scenes of Any Anxious body. These are the stories of household economics and children growing up too quickly. There is anxiety in the words of an old man recalling his first memory. There is solace in the stories of young lovers navigating Chicago’s streets. Kolaya is an historian, and the charm of her writing comes from her talent of pulling manuscripts from the memories of the men and women who came before her.

The long poem “Reckoning” is worth the price of the book alone. In it she draws upon two texts: the notepad her great-grandmother used to communicate to her family while in hospice and her grandmother’s twenty-page letter to her children. The first is filled with little calls for assistance, the second is a confession. It is the story of two generations of women, the narrative of one’s resistant exit interwoven with another’s grasping. They are two different experiences, but they encapsulate the same struggle for survival. Kolaya writes of her grandmother:

She’d made it far enough -- seventh grade -- to know how to handle guys like Owens who’d get you up against the counter and grow a thousand hands.

And then her husband when she gets home 2 a.m. Didn’t he know she’d spent her night like this swatting paw after paw?

Didn’t he know she just wanted to sit out on the porch put her feet up and light up a Viceroy like a lady? (47)

In only a few pages, “Reckoning” records two journeys of life, marriage and the debts we leave behind -- financial as well as familial. The poem ends with a photo of an expenses/assets list in her grandmother’s notepad, written “in someone else’s hand” (25). In words one intuits are as much Kolaya’s as her great-grandmother’s, they read, “We/ will never/ pay for this” (53). And how could we? These are the debts, the relationships that shape our time here. All of these things we continue to pass on if not unpaid, then forgotten. That is until we find them. And write.

The book ends with lines inspired by Ephesians. As we anxious bodies find solace in the lesson that our time is short and there is nowhere to go but down, we do so while quoting from “You Were Dead.” As you contemplate these debts, someday you will

remember that at one time

you lived among the natives and in you

the whole world was joined together. (83)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chrissy Kolaya is a poet and fiction writer. Her short fiction has been included in the anthologies New Sudden Fiction (Norton) and Fiction on a Stick (Milkweed Editions). Her poems and fiction have appeared in a number of literary journals.

She has received a Norman Mailer Writers Colony summer scholarship, an Anderson Center for Interdisciplinary Studies fellowship, a Loft Mentor Series Award in Poetry, and grants from the Minnesota State Arts Board, the Lake Region Arts Council, and the University of Minnesota. She teaches writing at the University of Minnesota Morris.

Joshua P. Preston is a graduate of the University of Minnesota Morris and currently a research fellow at Baylor College of Medicine's Initiative on Neuroscience and Law. He is the curator of Giraffes Drawn By People Who Should Not Be Drawing Giraffes and his writings have appeared or are forthcoming in The Rain Taxi Review of Books, The Humanist, and MAYDAY Magazine. Find him online at www.JPPreston.com.

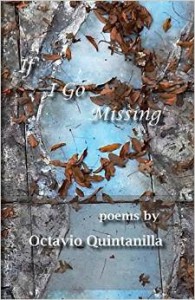

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "If I Go Missing" by Octavio Quintanilla

If I Go Missing

by Octavio Quintanilla

Reviewed by Luis Martinez

There is a darkness driving the current in Octavio Quintanilla’s debut collection, If I Go Missing, and I’m standing by the edge wondering what would happen if I dove in. I want to. Perhaps, I’d too admit myself a fond admirer of the butcher as the speaker in the first poem of the collection, The Left Hand, “Last night, it (my hand) got chopped clean/by a butcher’s knife, weird/ because as a boy I admired butchers/ and liked their knives.” In the same poem, Quintanilla explores what our hands are called to do, as they constantly force us out of our selves:

the dream in which I lose my left hand

doing a job I wasn’t born to do.

Sometimes I’m picking trash

on the side of the highway.

Other times, I’m saving a drowning man.

Darkness drives the current. “Revise toward strangeness,” is probably some of the best advice I’ve received as a poet. Poems that do so, often have beautiful endings: “And the night returns, and so does the river,/ and the hand that rides the current/ to the ocean/ and refuses to drown.”

In Tough Guy, the speaker notes, “When drunk, he pours milk/ between the legs of a beautiful girl,/ and licks.” Nourishment through artificiality. Something I fell in love with because how many times do we labor to find substitutes for things that already serve us pleasure. Quintanilla delivers a new strangeness. Images are released, “like frightened birds/ out of their cages.” This is book you’ll take orally, touch your lips, stare at your fingertips, bring them to your nose and get a taste of the beautiful unfamiliar.

One of the many things I like from this collection is that this isn’t a book about one thing. Not a project book. You won’t read the same poem over and over in different forms. It displays enviable range, from poems about fatherhood, immigration, love, death, and class. He’ll tell us about love, in Tell Them Love is Found, “Tell your mother about us…Tell them that I’ll keep returning to this house/ And gently take what is no longer theirs,” then he’ll spell poverty, “Now we are going somewhere./ Let us rejoice, then, and remember the days/ when our tongue was the only meat/ we could bite into.” Read this and learn the beauty tucked under the everyday.

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Heath Course Pak" by Tan Lin

Heath Course Pak

by Tan Lin

Reviewed by AB Gorham

no ambient citation is a caricature of itself

wide

there are no readers here

eyeswide in a wide stare

“As cinematic display, the magazine/book today functions vestigially i.e. most people who read them are looking at the titles of a movie very slowly, i.e. with slightly more retention than film images. Retention studies indicate that students who read books on computer screens forget or mis-remember content at twice the rate of conventional readers…People don’t read text so much as look at it…skimming, fanning, page flipping, reading books about books, blurb reading, browsing or locating a book in a spectrum of colors, binding styles, shelf-heights, and library floors, or even simple forgetting, etc., constitute earlier non-reading, pre-digital formats of text processing.”

SO if Lin translates these originally digital images onto a book’s paper page, will the content prove more memorable? The materiality of this book is puzzling. For a book that seems to, by all means, dismantle the assumed sanctity of the book form, the decision to place primarily internet and computer screen information onto a flat, stationary, permanent page juxtaposes the frivolity of the book’s initial inquiry by giving it tenure, staying power between covers. The internet is mutable, it can disappear quicker than the time it takes to burn a book.

Can this book be about tempting memory?

“reading is regarded as a format of forgetfulness.”

The enactment of celebrity theory: our obsessions over the unattainable, the untouchable

The abstract line between respect and dissect

Legible but not readable

An artist’s book, Heath wears the veneer of the anti-aesthetic, a lá Dieter Roth, in that Lin also employs organic substances… it makes me think that the internet does have its version of organic processes, and much the way people struggled to find ways to preserve and prolong the shelf life of food in home storage, we are now faced with ways to contain the internet. A word typed into the search bar can lead purusers into a field of knowledge and interpretation that, after a punctuated amount of time, will take the shape of mold covering a slice of American cheese. The anti-aesthetic never promises delight, joy, any facet of pleasure, but ensures a statement will be made, usually about the nature of the form of the object in question. This 4”x7” book, with waxed covers, slick paper, and at times unreadable pages does manage to contain a large amount of information, including information that can be further researched on the internet, as can any book, but at the time that some of these website pathways are followed, many of them may be defunct. I suppose even a defunct webpage can house a link furthering the lineage.

This is not for reading,

beginning with Samuel Pepys’s diary

“and their emotions approximate / windows and function as labels // and this is true. and this is not true”

I have to say, though, that I don’t particularly enjoy thinking about the internet in this way. So much of the internet is tedium to me, and Lin’s book does very little to alleviate that tedium. This book is a container as a jar is for a science experiment, and many of its internal parts, workings, are dead by their very existence on the page. Doesn’t the internet die when photographed and printed on a page? Or is this like saying that a life dies when it is recorded onto the page? Much information & little knowing. What is interesting is the very nature of this book as a diary, which is a direct record to a particular span of time. In this way, the ads and emails are the purest, most precise way of replicating a period of time spent on the internet. Then again, this is precisely the way in which this book deviates from the usual format of a diary, in that a diary often contains the most important/memorable information from the day; the events that fall away at the end of the day into the tedium abyss of non-remembering. If I think about the possible parallels between Pepy’s diary and the nature of Lin’s Heath, I am most alert to the concept of churches burning in London and the death of Heath Ledger as being a kind of church-burning, that is, under the assumption that being a celebrity constitutes being sort of a religion.

we can ask who wrote this

but how can we answer that if we don’t

“looking at someone else reading”

“Lin’s interest in works authored by a network”

“a derivative work”

[ Copyright: an image or idea or work that is in a

FIXED FORM OF EXPRESSION

appropriated material, material appropriate for this particular work

a terrible, dirty word ]

appropriate is

the pure attention that reviews demand

& this book refuses to open itself up to the being of Ledger

instead writhes in his been

rumors lisping in the corners of a great hall

I SUPPOSE WHERE I’M GOING WITH THIS is to think about the final section of the book, the interview between Lin and Chris Alexander, Kristen Gallagher, and Gordon Tapper, and how their insightful, thoughtful, intelligent and academic questions and responses to Lin’s work constitute an interesting take on what I’ve come to view (over the last couple of months of moving through this book and researching all that I can about what the superiorly smart have already said about Lin and his work) as a mass-distributed artist’s book. The concept of “non-reading” is nothing new to the book arts world, and really, when we think of this book as more of a deviation from the book arts world than a deviation away from the world of literature, the themes begin to align with the recorded history.

Pepy’s diary functions within the book similarly to the number of artist’s books Johanna Drucker explores in her book A Century of Artist’s Books, more specifically in the chapter on “Book as Document”, when she cites the use of diary entries as a means of building an identity. Drucker’s examples all employ the diary as a means to excavate the self, but this doesn’t coincide with Lin’s use of diary entries as a stand-in for personal revelation. In the case of Lin, incorporating diary entries is more an act of documentation of the Gutenberg Project kind (its position as the ultimate broker for all things literary and accessible. If not a broker, then more of a library for people lucky enough to be able to afford access to the internet.) Lin’s use of diary entries works more as a form of expression than it does reveal actual content. While the collage of time and space markers that is Lin’s book reveals something about the attention span and interests of the author, it is more the experience than commentary on the experience. Drucker continues her exploration of artist’s book that feature diary entries, mentioning a project by Christian Botlanski titled Object Belonging to an Inhabitant of Oxford, in which he does what Drucker terms “demographic mapping,” or, the “sense that person-ness and individuality are inflections of a generic and socially constructed sense of identity” (337). Here is where Drucker’s ideas help illuminate and contextualize Lin’s work in Heath. Lin’s book also catalogues numerous forms of expression, including screen shots of Blimpie ads from the internet, Wikipedia articles, but does so in a way that never fully reveals the detailed nature of the author’s memories. Instead, Heath catalogues the line of inquiry Lin follows within a certain span of time. In fact, time is warped within Lin’s text, in that the second half of the book exists as a revealed version of the first half of the book. Heath uses “process” as its organizing aesthetic. Beauty as a play-by-play, intimate internet trajectory, as an unraveling of weblinks, computer associations. The book doesn’t follow a traceable sequence that in any way resembles a narrative. Rather, it moves like a lens focusing in on its subject: at first wearing a veil of photographed or screen-captured pages including post-it notes and editorial marks, and then a peeling away of that veil, leaving a finale of clean drafts and raw data.

Discourse / Heathcourse

Notes Towards a Definition of Culture, as is whirlpools around one celebrity’s death in an attempt to reconcile with what it means we don’t know at all. Discourse documentation of life&death in one package the life of a death as it unravels on the internet.

“Can it be a read and written text simultaneously?”

Post-It Note Erasure

Post it: censorship: pale-yellow sharp-edged curtain

Post it: mundane page for miniscule writing

Post it: post it; what’s slipped past you, what do you hide

editor’s marks in pencil = documentation of process

the experience not of reading but of passing time

ideas flinging themselves off of the rocks

monkeys cooling their fur bodies

in water then swimming back

Screen Shot: smiling ox

not to be read but to be investigated

Heath Ledger / Health Leger

a derivative work: pastiche: collage: collection

how long does it take to read a text

how long is my attention span

recall empathy reward understanding

Lin’s avoidance of identity maps nicely onto Rem Koolhass’s fretting in his essay “Junkspace” in that “’Identity’ is the new junk food for the dispossessed” (1). By avoidance of identity, I mean a refusal to pair oneself down; and eclectic sense of self that is more collector than the sum of the collected parts. A virtual pawnshop where the value of the online page changes by This book is utterly dated, from the screen shots of emails and internet ads, to the photos of cell phone screens. Heath balloons into a space saturated with internet noise and a cacophony of product labels shouting superlatives. “Their eyes were made of search engines like a search engine.” The redundancy of repetition inflates its own skin, making room for rumination. “Museums are sanctimonious junkspace; there is no sturdier aura than holiness” writes Koolhass towards the end of the essay, tapping into the upward momentum that re-contextualization can offer an object or idea. Museums preserve, even elevate and object’s status in history by giving it an assigned space as long as the building stands. “Junkspace” describes a particularly cluttered, claustrophobic view of our compartmentalized lives, one that Heath seems to perpetuate. The record of process does not utilize editing. We also know that no diary record can be complete, down to each shift in weight, each nostril flare.

Heath Ledger enters as interruption, and sends another portion of my brain spinning.

This is multi-tasking and to find meaning is to contain all processes at once and impossible.

Lin’s “anti-aesthetic” approach to a book reminds me of Dieter Roth’s daily mirror book 1961 in which he cut out and blew up sections of a newspaper, including ads, parts of stories, titles, and made the ink appear in its vector form (pixels, matrix), rendering the book “unreadable,” and simultaneously asking the reader/viewer to question the roll of the book, more specifically, the codex, in our everyday lives.

The experiential terrain of this book does not necessarily demand an in-depth knowledge of the internet. On the contrary, seeing the advertisements and internet-scripted pages out of their original context estranges the otherwise mundane information, and as a result, initially tricks the reader into paying attention to detail to which they would not otherwise pay attention. This attention, however, only lasts until the skimming mode takes over. It is in this mode that I traverse through this book, looking for bits of information and interesting language on which I can land for a while among the noise.

“someone said you are already dead so stop singing”

“someone said you are already transparent so stop glistening”

I said

he never wanted me to read

he only wanted my attention

which is much more to ask for

my tendency to skip/skim

the photo of a doll’s head with blacked-out eyes

oversized coffee mug with watered down coffee remnants

a red fly swatter that sings each time it strikes a surface

a black iron teapot well seasoned with rust

socks folded into a cloth fist

fruit flies scavenge stark the white curtain

that separates my inventory from the floating leaves

outside

Heath inventories a new nature

DIAGNOSIS:

The magazine feel of the pages

The cover: waxed paper, tacky, and is quite unpleasant to the touch

while the waxy book covers may help some with the book’s durability, I find it difficult to enjoy holding it.

The fifth page of the book following the title page is the initial instance of a book infiltrated by computer layout. On the bottom of the page lies a screen capture from the internet , which includes Google’s browser bar and a Web hyperlink to a cut-off definition to “The Arts of Contingency.” While this screen capture isn’t aesthetically pleasing, I’m going to assume that aesthetics, as in the measurement of beauty, is not the book’s foremost agenda. Using the landscape (a new landscape! What would Bachelard say of this landscape? It is fleeting! It can be a difficult place in which we find reverence.) of the internet, i.e. a pop-up ad, as the vehicle in a simile that drives a comparison to beauty and utility. Conveying information can be beautiful, as the record of an internet moment can be beautiful in the same way that memory is beautiful in a very utilitarian way.

The front cover, as is most of the text, is printed in courier font, which is a monospaced typeface originally developed for typewriters. Lin’s choice to utilize this typeface seems at odds with the otherwise “high-techiness” of the integrated internet fragments and other screen caps. Courier gives the appearance of an outdated form of written expression that even Congress has moved beyond.

This book has done away with transition, yet it does maintain the formal structural element of endsheets—stained endsheets—a well-worn book grease stains on the endsheets

Lin’s book has a pastiche quality to it that is further punctuated by photocopied notes written to him by hand. The hand-written notes are the most human of all the moments in the book. Although the notes are seemingly indirectly related/linked to Lin’s ideas about celebrity, they do offer a brief moment of biographical insight, a formulated token that reaches out to a product beyond the book’s capacity, and points with a human finger back to the book’s author. The handwritten notes serve as a catalogue of handwriting samples. I try and assume personality traits associated with a person whom sharpens the curves in their ‘s’s’, and in this way, I’m outside of the book while working through the book. If good writing really makes you stop and look away from the page, then good formatting can do the same. The handwriting worms through the otherwise technologically focused pages; they stand as hieroglyphics, palimpsests of the past. As they point to a time before moveable type, they also work as a very timely marker of the technological advances that have allowed bookmakers to scan in and print images of handwriting. Within these pages nests the heart of the artichoke: we are skilled at drumming up the past, at presenting direct references to times passed, because we have the ability of the future to do so.

Despite the clunky page design of the collaged computer images and courier text, this book manages some really beautiful, poetic moments. Most of my reactions to Lin’s book involve thinking about the form rather than the content. I become obsessed with what the existence of this book says about the role of a book in general, and how this tedium/non-reading makes me question the act of reading anything. I am rarely enthralled in the words on the page.

I believe we are no longer calling this literature, although:

Mining through, “they are un-specific with sand” I’ve found something I can roll around in my mouth for a while. I believe this phrase lovely for the way I remember sand is un-specific and therefore makes me feel so un-specific, finding sinking footing along the water line, and un-specific because sand as a body is comprised of billions of tiny and very specific particles that refuse to overlap one another, and never will assume one another into their hard-bordered bodies, but will organize their allotted space, their container as perfectly as possible to be seen with the eye. A body of sand is organized like a network, and so, un-specific because of its multitude.

The great reveal that occurs towards the end of the book, in which I slowly realize that the pages I’m reading are the pages that I first came across in the beginning of the book, except for this time they are sans post-it note cloak. I feel both duped and curious as to the meaning within a book that cycles back on itself. This, of course, is where we find out that “meaning” lies mainly within the form of the book, and less so within its content.

The interview at the back of the book works like an extended colophon that incorporates the details of the project’s evolution, down to that the fact that book both contains the notion of evolution of a thought, of a search, of the transition of a celebrity entering into his historical context as a figure of the past. This book without the final interview is all the more mystifying, although it’s difficult to speak of any book without immediately thinking of the book’s accompanying web results. Every book can be Googled, and Lin’s book is Google.

“Here it seems that the non-artists got it right and the artists got it plagiarized.”

There is so much to say about this book, and I believe people will continue to grapple with its strange existence for years to come.

I don’t think he is saying, here, look at this, look closer, isn’t this interesting? Because it seems that so much of internet writing is a means to an end, the way computer code stretches across a screen and demands that the computer function. Ambient electronic noise contained in a book.

“In the end, it did not matter which newspaper I began or ended with or which sit-com I happened to be watching or re-watching. All physical activity, like a spike on and EKG monitor or prime time viewing habits, shall be inserted after the fact. All images shall materialize from a database with a date stamp and a physical cue and all this shall be prefigured by an earlier occurrence, an interval, a product, a memoir, a linked page, a pre-recorded format, a typeface, a digital genre, a promise, and so it was in this particular instance—”

--------------------------------------

Author Bio:

Tan Lin is the author of Lotion Bullwhip Giraffe (Sun & Moon Press, 1996), BLIPSOAK01 (Atelos, 2003), ambience is a novel with a logo (Katalanché Press, 2007), HEATH (plagiarism/outsource) (Zasterle Press, 2009), Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004. The Joy of Cooking [AIRPORT NOVEL MUSICAL POEM PAINTING FILM PHOTO HALLUCINATION LANDSCAPE] (Wesleyan University Press, 2010), INSOMNIA AND THE AUNT (Kenning Editions, 2011), and HEATH COURSE PAK (Counterpath Press, 2012). His work has appeared in numerous journals including Conjunctions, Artforum, Cabinet, New York Times Book Review, Art in America, and Purple. His video, theatrical and LCD work have been shown at the Marianne Boesky Gallery, Yale Art Museum, Sophienholm Museum (Copenhagen), Ontological Hysterical Theatre, and as part of the Whitney Museum of American Art's Soundcheck Series. Lin is the recipient of a Getty Distinguished Scholar Grant for 2004-2005 and a Warhol Foundation/Creative Capital Arts Writing Grant to complete a book-length study of the writings of Andy Warhol. He has taught at the University of Virginia and Cal Arts, and currently teaches creative writing at New Jersey City University.

Reviewer Bio:

AB Gorham is a book artist and writer, originally hailing from Montana. She recently graduated from The University of Alabama, where she received her MFA in Poetry (2012), and her MFA in Book Arts (2014).

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Twine" by David Koehn

"Now that I have read Twine, I believe I could recognize a Koehn poem anywhere."

"Now that I have read Twine, I believe I could recognize a Koehn poem anywhere."

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Particle and Wave" by Benjamin Landry

Particle and Wave Benjamin Landry

University of Chicago Press, April 2014

Reviewed by Elizabeth O'Brien

Is a book of poetry's structural conceit descriptive or prescriptive? And how does a conceit inform the experience of reading the individual poems within a collection? I find myself thinking about these questions lately because so many books of contemporary poetry are organized around definable structural conceits. Benjamin Landry's new collection, "Particle and Wave," for example, is built around the periodic table of elements.

Landry chooses 40 of the 118 known elements and devotes a poem to each, in a range of forms varying from orderly stanzas to columns to erasures. Although written in free verse, there are several nods to rhyme and alliteration, as in "Au," which opens, "'Slate,' he said. And it was late." The voice is airy without being evasive; authoritative without being arrogant.

The poems mix technical diction with a more poetic one: "H," for instance, which represents hydrogen, begins with a line that could come straight from an elementary science text, but then is quickly juxtaposed with the more mythic:

Imagine the heat generated

by Daphne transformed into laurel

and you can begin to feel

what the electron feels

in renouncing its steady orbit.

The way Landry's works with both the scientific and the literary in the first pages honors the book's framework, setting up a tone that alternates between these modes. And, although the book begins quietly, the poems gather momentum as the experiments with form become more deliberate, and themes and images initiated in early poems are revisited. As the book progresses, the sense develops that something meaningful is at stake, as when the idea that "Some of us determine/whether an atom stays/together or falls apart" in "Cr" is complicated by Landry's later piece, "U":

We split the atom because we could

and are now outfitting cockroaches with microphones;

our drones have a bird's eye imagination.

Atomic bombs are a natural preoccupation for a book like this to have, and the assertion made hereabout the relationship between power and intention--"We split the atom because we could"--is chilling in its simplicity.

But on the whole, these poems are less preoccupied with scientific subjects than one might expect, opting more often for personal narrative, and using the titular elements as phonemic rather than material symbols, as in "Br," which connects its title with the sound of a ringing phone, rather than with Bromine, a chemical in the halogen group. Likewise, "Ba," features final lines referring in French to lambs. As far as Earth's building blocks and science are concerned, we are given several references to the splitting of atoms, an epigraph from Marie Curie, and a series of moments that describe the natural world, or touch lightly on intersections between science and philosophy or morality.

But to return to the earlier question of how a book's conceit informs the reading of poems--I did find myself judging this book based on my expectations for how its use of the periodic table could play out. I was expecting there to somehow be more science, although now it's hard to say how.

Books with strong organizing frameworks are appealing because an identifiable overarching structure--like adapting the periodic table for poetry's sake--offers an automatic entry point for readers. It's satisfying to sense what a new book from a new poet is likely to be "about." But then, of course, the poet must move beyond the initial impulse that generated the poems: the whole must be greater than its individual poetic parts. And I suspect that books that use a formal conceit, or otherwise signal that they are about a specific subject are at a disadvantage, then, because although they draw readers in with the promise of a hook, they also invite readers to approach with preconceived expectations.

The best part of any new book of poetry, Landry's certainly included, is that you never know exactly what to expect--even if you think you know what to expect. "Particle and Wave" has a strong organizing conceit that is sure to attract attention. But the poems are also individually innovative, offering interesting moments when the scientific and the poetic meet.

-----------------------------------------------------------

Benjamin Landry is a Meijer Post-MFA Fellow at the University of Michigan and the author of An Ocean Away.

Elizabeth O’Brien writes poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. Her work has appeared inThe New England Review, Diagram, decomP, Sixth Finch, PANK, Swink, New Pages, The Pinch, Versal, Juked, The Leveler, The Liner, Euphony, A capella Zoo,Slice, The Emerson Review, Flashquake, and elsewhere. She is a graduate student at the University of Minnesota and can be found online at elizabethobrien.net.

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "All You Do Is Perceive" by Joy Katz

All You Do Is Perceive

by Joy Katz

Four Way Books, 2013

Reviewed by Kay Cosgrove

Some thirteen years ago in a gale of wind,

On a foil packet of shampoo,

After a prayer with no words,

When a spoon leaves a firm imprint,

During the last known hours,

As the meltdown hit groundwater,

When we signed off on everything,

And then, a face: the woundable face of a boy.

(“WHICH FROM THAT TIME INFUS’D SWEETNESS INTO MY HEART”)

So concludes the first poem in Joy Katz’s latest collection, All You Do Is Perceive. This first poem, set off from the rest of the book, reads as an invocation to the muse, who, in this case, happens to be the adopted son of the speaker. Written as one long, breathless sentence, “WHICH FROM THAT TIME INFUS’D SWEETNESS INTO MY HEART” establishes the arc of the book as akin to “a basket tossed weightlessly” (line 13). The poems float from page to page, linked by their shared perception of the world through the eyes of a speaker, who, in turn, sees like a child again. One can feel the joy bursting forth from the pages of this collection, and as readers, we get to share in it through the language of the poems, like children in awe.

Take, for example, the poem “[NOON, F TRAIN].” In it, Katz creates a simple, beautiful portrait of a daily life. Nothing much happens in the poem: there is a woman, arguably the speaker, and she rides the F train home, reading a book. Written in a block of prose, “[NOON, F TRAIN]” unfolds like a movie clip before the reader’s eyes, as if we are there with her on the train. Though the echo of Eliot (“there is time enough…”) might be a bit heavy-handed as an allusion, this repeated phrase evokes a mood that allows the reader to see this ordinary scene through new eyes, to “pass up into the world and leave nothing behind…” (“[NOON, F TRAIN]”).

Much of the book reflects on being a woman in the world, specifically, a woman in relation to a man and/or a child. The speaker both identifies with and makes a distinction between herself and the other ‘characters’ in the collection, the man and the child, who are perhaps representative of the family unit. There is the relationship to a beloved: “his song is the door back to the room/I am composed of the notes” (“DEATH IS SOMETHING ENTIRELY ELSE”), the relationship to the son: “we are sugared in a medium, he and I/He is smiling/Happiness is on me like a scratch in a car door” (“MOTHER’S LOVE”), and the relationship to both of them: “how she must hold to everyone and swim them to the same shore” (“HE LAUGHS TOO HARD ABOUT THE WINE”). In each poem, the speaker, at times in a playful tone and at times rather gravely, highlights these relationships in order to underscore her femininity - the defining difference between both the beloved and the son. This accounts for a different perception of the world, as in the poem “THE LETTUCE BAG” (“If labias were in/season, their tender interiors, their roundness, would be touched by/the grocer’s mist”), or the fourth stanza of “THE IMAGINATION, DRUNK WITH PROHIBITIONS”:

Womanhood is more embarrassing than manhood.

If the woman is old, breakfast is hopeless.

If breakfast is brioche, it becomes less frightening.

Insouciant is more French than nuance,

disappointment more French than matinee,

London more suave than Paris.

(“THE IMAGINATION, DRUNK WITH PROHIBITIONS”)

There is even something childlike in the more serious meditations on womanhood and motherhood, something that insists on finding delight in the most unlikely places. Katz establishes this child-like wonder largely through her playful use of anaphora and repeated images. Katz succeeds in using the phrase “Department of” twenty-one times in “DEATH IS SOMETHING ENTIRELY ELSE”, and in “MOTHER’S LOVE,” she similarly repeats the opening few words again and again so that the poem begins to sound like a song. Less original, but just as striking, is the ending of “JUST A SECOND AGO”, which relies on anaphora to establish an eerie tone of possibility: “just a second ago/while you were crossing the street/while you were finishing your lunch/while you were handing me your terrible secret—“ (lines 25-28). Finally, there is the sky, the air, the natural world we inhabit, and the language we use to understand nature, as in the poem “WE ARE WALKING INTO THE SUNSET”:

Look, the sky has become stained glass made of meat!

You keep talking, as if in utter faith that life will go on forever.

Yet that in itself is lovely. Keep talking. What is more of a pleasure to

See, a moon as big as a bison head or the face of a friend, talking?

("WE ARE WALKING INTO THE SUNSET”)

Another level of perception present in the collection is the perception of the world through the eyes of a writer, specifically, a woman writer. Again and again, Katz acknowledges that she is at work in All You Do Is Perceive, that she has “a few minutes left to write” (“THE COMPOSER”), that “mornings [she] wrote and workmen/raised up their nets” (“ALL YOU DO IS PERCEIVE”). The speaker seems to be trying to reconcile the world with her place in it, a task that might be impossible through poetry:

I get a great, blank feeling, driving. I am a girl, driving.

Poems aren’t labor, progress, robber barons—not poems. Four men sit

in recliners on a grand side lot. Lush weeds, what grows without regard.

Girls’ names no one thinks to pick: Lorraine. Here is the street where

I lived. Where I can be—nothing. Four p.m., light rain, no one asks

what I am writing. A room livingly painted sends its notion into me.

(“TO A SMALL POSTINDUSTRIAL CITY”)

All You Do Is Perceive explores a way of being in the world that relies on consciousness alone, on paying attention to even the most mundane aspects of life, such as carting the empties to the dump (“BIG BABY”) or admitting that being “alone with the baby is boring” (“MOTHER’S LOVE”). In this collection, there is joy even in sorrow, and Katz teaches her readers to notice, to be alert, “to prefer autumn's bigger name, fall, and/its battering change” (“BIG BABY”). All of the poems, as with all of the aspects of life, accumulate one on top of another. Some are happy, some less so, but, through the eyes of a new baby, a son, they can be beautiful, like a basket as it comes crashing back down to earth:

That becomes a basket tossed weightlessly,

As a baby is handed through the air to us,

In the final seconds of the fourth quarter,

Halfway through the preface,

After they set us on fire…

(“WHICH FROM THAT TIME INFUS’D SWEETNESS INTO MY HEART”)

CUTBANK REVIEWS: Hungry Moon by Henrietta Goodman

Eat your death-wich, dear: A review by Sharma Shields

Eat your death-wich, dear: A review by Sharma Shields

CUTBANK REVIEWS: ERUV by Eryn Green

Denver poet Eryn Green's manuscript "ERUV" was selected the winner of this year's Yale Younger Poets prize.

Denver poet Eryn Green's manuscript "ERUV" was selected the winner of this year's Yale Younger Poets prize.

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Render/An Apocalypse" by Rebecca Gayle Howell

"Howell has given the literary world a truly unique offering, which finds the common ground between poetry, horror, and (human) nature."

"Howell has given the literary world a truly unique offering, which finds the common ground between poetry, horror, and (human) nature."

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "I Can Almost See the Clouds of Dust" by Yu Xiang

"The speaker experiences the flow of the present moment through time, all while in a daze. It is in fact the reverie that allows her to enter the flow of fleeting things, and as the poem closes she becomes one of those very things in the eyes of another daydreamer."

"The speaker experiences the flow of the present moment through time, all while in a daze. It is in fact the reverie that allows her to enter the flow of fleeting things, and as the poem closes she becomes one of those very things in the eyes of another daydreamer."

CUTBANK REVIEWS: "Sudden Loss of Dignity" by Gary Soto

Review by Luis Alberto Martinez

Review by Luis Alberto Martinez

CUTBANK REVIEWS: Young Tambling by Kate Greenstreet

CUTBANK REVIEWS: Kiss the Stranger by Kristy Odelius and Timothy Yu

CUTBANK REVIEWS: Collected Body by Valzhyna Mort

"Our situations feel precarious. The stakes are high." On new years, resolutions, and the freedom to try

"Our resolutions, our rebirths, they elbow space for our failures to become part of our story instead of part of our identity. But I’ve come to suspect that the personal aperture that exposes bullshit or shades it is not the gauge to adjust."

Read More