Long Way From, Long Time Since features letters written from writers, to writers, living or dead. Send us your queries and inquiries, your best wishes and arguments, and help us explore correspondence as a creative form. For letter submission guidelines, visit cutbankonline.org/submit/web. To submit to our print edition, please see cutbankonline.org/submit/print or email cutbankonline@gmail.com.

Dear Philene –

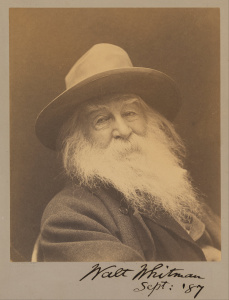

I never did answer the question you asked in New Delhi. You probably forgot about it when we ran from the police station after they tried extorting me for reporting the pick-pocket. But your request has haunted me, “Tell me more about Whitman’s genius.” Volumes have been written about Walt and my letter, sketched on this train to Agra, may not give you what you want to know but I’ll try.

I’d say, he knew how to pause, how to observe, how to synthesize his deft observations into a written micro view for an intuited macro view. To use the description of Wordsworth on what poets do, “write strong feelings recollected in tranquility.”

This required a piece of his soul, less dramatically, a primary ability to feel something. My professor once said that most of his counseling clients fell asleep telling their own story. They couldn’t feel anything about their own lives, let alone anyone or anything else.

I mourn that inability in an emotionally blunted American culture. Perhaps it’s different in Holland. Empathy and the ability to feel is important not just for a poet, but for a person. I read that some communication scholars believe empathy is the most important communication skill.

Empathy is the ability to feel my experience first and then feel what others feel. Whitman had that ability, along with powers of emotional recall and disclosure. He was moved to strong words not just when looking at a stack of arms and legs in a Civil War battlefield hospital, but during all encounters.

Yet if empathy was the only skill, anyone could write like Whitman. It also takes linguistic gifts to the degree that a writer can create something memorable: or in the words of David Tracy, writing in The Analogical Imagination, a classic. Tracy wrote that a classic speaks to all generations. Walt did.

I think he was a writer conscious of his legacy. In “Poets to Come,” he reaches out to people like you and me, writers haunted by wind and air and water and everything. “I myself but write one or two indicative words for the future,/ I but advance a moment only to wheel and hurry back in the darkness/ I am a man who, sauntering along without fully stopping,/ turns a casual look upon you and then averts his face.”

But he’s coy, for he never just sauntered along, casually looking. He stops, looks deeply and feels profoundly. Many writers can stop, some can look, but not all feel with a full and gutty primal empathy.

Looking down the road, he bows to the future in the poem you liked, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” when he imagines you and I peering down to the Brooklyn River, seeing the shadows cast by our hair upon the tide flow. His writing of time and tide captured the flow of history, and that is why we still read him, it is why his work is classic.

Raising the bar of his observations, Walt grasped intellectual/philosophical/mythological history and their role in the development of our human story. This is something offered by all great artists and all works of magnum status. Here’s a teaspoon from a large volume, “Song of Myself.”

Taking myself the exact dimensions of Jehovah and laying them away

Lithographing Kronos and Zeus his son, and Hercules his grandson

Buying drafts of Osiris and Iris and Belus and Brahma and Adonai

In my portfolio placing Manitou loose and Allah on a leaf and the crucifix engraved

With Odin, and the hideous-faced Mexitil, and all idols and images

He did not lazily pause, his curiosity and ambition far too strong: “I think I will do nothing for a long time but listen.” Listening is no small feat, for true listening it is an active investment in the now.

I’m reminded of Rilke, in his poem, “The Panther.” He watched the caged, pacing animal for weeks and then wrote the poem. Neither was Walt content until his contentedness was grounded in the pause, the listening body, peering from under droopy eyelids. How is this for stop, listen, look and learn: “I think I could turn and live awhile with the animals…they are so placid and self-contained, / I stand and LOOK at them sometimes half the day long.”

His linguistic skill, observational prowess and patience, empathy, intellectual maturity, breadth of synthesis, and emotional recall combined with a fierce appreciation and love for the world… that’s genius.

An American poet, Louis Simpson, once wrote that poets should, “Have a stomach that can digest/ Rubber, coal, uranium, moons, poems./ Like the shark, it contains a shoe./ It must swim for miles through the desert/ Uttering cries that are almost human.”

Even by that toothy measure, I’d say Walt qualified. His telltale cry was a barbaric yawp, formed out of a comprehensive vision of and full bodied response to the total human and cosmic experience.

I suspect if anyone had sliced open the belly of Mr. Whitman, they would have found all manner of dark and light treasures, fragments of notebooks and an attending grief from bedrooms and battlefields.

As for your question about poets that stand on his shoulders, I like Maya Angelou and Carl Sandburg. Angelou anchors history in the present like no one I’ve known, except perhaps Anna Ahkmatova. Angelou’s poem on the inauguration of President Bill Clinton stuns me in its perfection.

And Sandburg, writing deeply of Abraham Lincoln, celebrated the pure physical labor of man and woman. I name it, Sandburgian Socialism and Midwestern Storycism, a sculpting of broad-shouldered and redemptive myth from hard materials. Sandburg stands squarely in the Chicago tradition of loving critic, his heart broken by city and country.

There’s more Philene, but my train is stopping and I’m off to see the Taj Mahal. I’ll write more about Mr. Whitman, but in the meantime, take a good bite of what’s in front of you, and keep writing.

Cordially,

Greg

Gregory Ormson earned an M.A. in English from Northern Michigan University in Marquette, Michigan. He’s worked as a journalist, business writer, and sports writer. His work has been published in Quarterly West, The Trinity Seminary Review, The Seventh Quarry (Wales), Elephant Journal, The Yoga Blog, Horizons and Entrée.’ He won a 13-word tweet contest sponsored by The Indiana Review. He lives in Hawaii where he does yoga, rides his Harley-Davidson, and writes.