Paper Dolls: A Love Letter for Zelda

by Jody Kennedy

Zelda Fitzgerald, “Self-Portrait,” watercolor, probably early 1940s. Image from Wikipedia

“I'm so full of confetti I could give birth to paper dolls.”

—Zelda Fitzgerald

Dearest Zelda,

So how does one address the Original Flapper, “It Girl” (second to the actress, Clara Bow), and baby vamp? Maybe just start by saying that I was enamored with you once? Remembered you when I lived in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Paris, and Juan-les-Pins, and on visits to Lake Geneva, Cap d'Antibes, and Saint Raphael? Considered you part of the Good Girl Bad Girl's Club (along with Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, and my maternal and paternal grandmothers, and great-grandmothers, among others)? Always wanted to be the happy-go-lucky version of you: the almost perfect WASP, well-heeled extrovert, the life of the party, flirting with waiters, dancing on tables, organizer of fabulous soirées, ballerina, goddess, inhaling Marlboro Reds and gin and tonics until in the end crashing and burning with you like Draper's beautiful boy, Icarus.

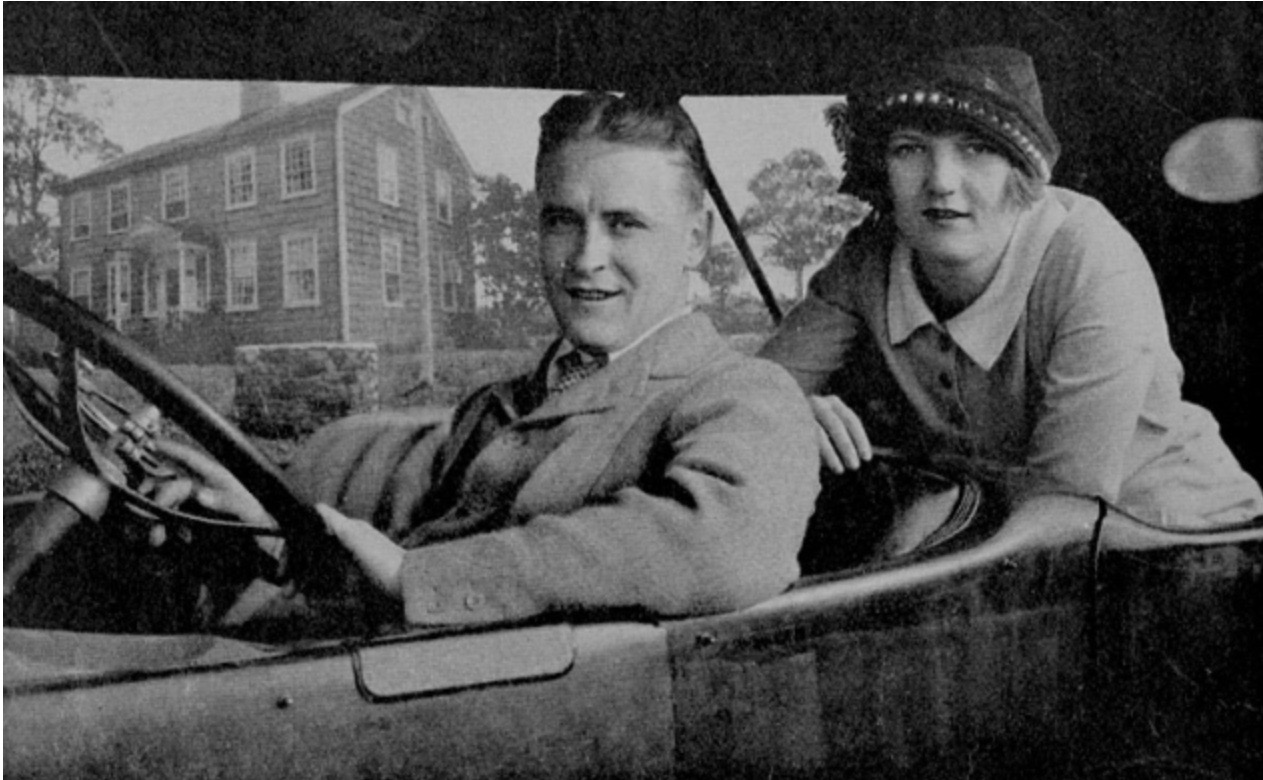

We were just kids when we met. I must have been around sixteen and you seemed forever immortalized at twenty-one. Like in that photograph of you and Scott posing in a car, your short hair hidden under a cloche hat and Scott's smile, contagious. It's strange to look back now and realize that you weren't much older than me though you seemed so grown-up, but doesn't everyone over nineteen seem ancient when you're still sixteen? I deliberately skipped over later photos of you looking puffy at Lake Annecy with Scott and then ten-year-old, Scottie, or you, a couple of years later, gaunt in a floral print apron standing with some paintings you'd entered in an exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art or that other image of you wearing a long dress and white ermine coat next to a tuxedoed Scott, both of your faces strained and your hands, especially, noticeably clenched. You seemed to be apparitions of your former selves, like wax figures found at Madame Tussaud's in London or the Musée Grevin in Paris.

“I ride boys’ motorcycles, chew gum, smoke in public, dance cheek to cheek, drink corn liquor and gin. I was the first to bob my hair and I sneak out at midnight to swim in the moonlight with boys at Catoma Creek and then show up at breakfast as though nothing had happened,” you wrote in your high school journal. Ditto to most of it (said my maternal grandmother and me).

My attraction to you bordered on obsessive, the same way my attraction to the 1920s, Saint Paul, Paris, and Gertrude Stein's Lost Generation did. And there's still sometimes a feeling of being like Rip Van Winkle playing catch up after waking from a long slumber along with a sometimes still intense longing to travel back to those early days meeting you and Scott and some of the gang in Ernest Hemingway's A Moveable Feast. Maybe another part of my attraction to you was because of a certain air de famille. My maternal grandmother, ten years your junior, came of age not far from Saint Paul's Summit Hill neighborhood where you and Scott and Scottie, then a newborn, had been living at the time. My grandmother was the furthest thing from a WASP, grew up poor but, like you, bobbed her hair, wore pants, loved to drink and dance, and at fifteen fell in love with and quickly married her Scott, a local gangster who kept her supplied in stolen diamonds, furs, and bootleg liquor.

Scott was lucky to have seen you dance. My maternal grandmother, who died the year I was born and who I only knew through stories, talked about coming back in her next life as a professional dancer. As a young girl I dreamt of being a ballerina but was rarely comfortable in my body or while dancing. I imagined you dancing though, your petite and feline body the opposite of my Irish-German peasant build, the same build that effectively killed my ambitions of becoming a world-famous model at fourteen, which would have been my ticket out of high school and out of the small Midwestern suburb where I grew up.

Scott turned out to be your ticket out of Montgomery and out of Dixie. I can understand how you fell for him: his Yankee otherness, his sense of humor, and his poetic streak. I searched my small Midwestern suburb for a jewel like that but always ended up with a mouthful of heavy metal, generic greeting cards, and lukewarm Budweiser. A Scott came much later for me and, despite doubts about getting married, I said yes because I'd planned to make a respectable man out of him. He was going to be Peter Maurin to my Dorothy Day, Charles VII (the Victorious) to my Joan of Arc. Did you feel like you were acting a part when you married Scott in the vestry at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York on April 2, 1920? A wedding in the vestry wasn't your dream. You wanted the whole Cathedral (and isn't a woman worthy of that?). “David,” the legend read, “David, David, Knight, Knight, Knight, and Miss Alabama Nobody.”

Zelda and F. Scott, 1920: Photograph courtesy of Princeton University Library

EASTER, 1920

for you, Zelda

Someone sent a lily and it made / the room smell so sweet / that first day of our honeymoon. / Lying in / bed the night before / watching you undress, / I noticed how flat and curvy / your stomach was, / just like a girl, I thought. / You disappeared under the covers / like the landscape in winter, / buried your face / between my legs and asked, / am I doing this right? / When you finished you rolled away / (pale from champagne) / and fell asleep / while I lay awake half the night, / my stomach tied up in knots / and certain that God had forsaken me.

We set up well-stocked bars: absinthe, brandy, bourbon, cognac, and seltzer delivered from Chez Jacques. On anniversaries we expected fresh cut flowers, boxes of chocolates, diamond pendant earrings, and other sweet nothings. We pulled on the skins of Rosalind (This Side of Paradise), Sally Carrol (The Ice Palace), Gloria (The Beautiful and the Damned), Daisy (The Great Gatsby), and Nicole (Tender Is the Night). We broke expensive dishes and threw around curses. Prisoner and jailer (one and the same), we refused to give up East and West Egg. Where would we have gone anyway? Back to Montgomery and back to our mothers? (Our mothers, our mothers: sweet, controlling thrift sale lovers.)

*

This letter is also for all of those women whose love lives don't fit neatly into a New York Times Modern Love column. Confession: it was easier to love you, Zelda, from afar, one dimensional (sometimes two, like in that footage of you and Scott at Sara and Gerald Murphy's villa in Antibes). I hate to admit it but I don't think we would have gotten along. There'd been a breach of confidence in 8th grade when my girlfriends accused me of flirting with boys at the roller rink, which completely floored me since my own perceptions were otherwise. Though it may not seem like much to you, that wound lingered for many years and laid the groundwork for a lifelong distrust, fair or not, of women. Maybe I was flirting and my girlfriends had seen past my blind spot. Maybe my deeper fear was this: that we women can't fool other women as easily as we can fool men. Or maybe the conflict lessened my guilt as I soon began to choose boys over those friends.

*

We moved to Saint Paul and searched for your ghost, gave birth to girls named Scottie, Savanah Rose, and Scout. We cooked under the influence of Pinot Noir, burned the Easter ham, threw in the towel. We used words like intrigued, ghastly, cat's pajamas and bee's knees, and it was such a smashing party last night, don't you think so, darling? We built altars to Marilyn and Madonna, Clara Bow and Rihanna, stuffed our faces with macaroons, cashews, and coconut donuts. We were called jazz babies and the first American flappers. We never learned to drive or play the markets.

*

Jody Kennedy’s maternal grandmother.

Most of the girls in the Good Girl Bad Girl's Club were afraid to be mothers. We: 1) avoided pregnancy at all costs. 2) had abortions. 3) left our children to be brought up by English nannies or left them temporarily or permanently like my paternal grandmother left my infant father at the Holy Innocents Home in Portland, Maine, or we left them during our stays at psychiatric hospitals or by our suicides. Most of the girls in the Good Girl Bad Girl's Club were generally more masculine than other women. We were called lesbians, bitches, sluts, tarts, troublemakers, and witches. What we lacked in maternal warmth we made up for in hyper-sexuality and goldmine diaries. (Scott didn't like your aggressive side and you called him a fairy on Rue Palatine.)

If there is such a thing as reincarnation, I'm convinced my last life was one of a man since much of this current one has been spent identifying as a man living in a woman's body. What does it actually feel like to be a woman or a man anyway? Is it really just the difference between skirts and pants, lipstick and combat boots and/or sexual preference? (The spirit is androgynous and all the rest is show business.) Or maybe it's simply a case of what Carl Jung called animus possession? Many of the girls in the Good Girls Bad Girl's Club seemed at times overly identified with our animus i.e. our masculine shadow. And when and if we became aware of the pattern, it was on us to begin the process of integrating the feminine and masculine sides of our psyche or risk being destroyed (jails, institutions, death) by said animus.

*

We left the East Coast and sailed to Le Havre, took trains to Paris and taxis to the French Riviera. We adopted words and expressions like: chez [insert favorite restaurant here], je ne sais quoi and apéritif. We lunched at the Murphy's Villa America, got tipsy and dove from cliffs on Cap d'Antibes during evening parties at Eden Roc. On beaches in Saint-Raphaël, we swam in the sea and in between reading Wharton and James, fell in love with dashing French military pilots.

*

My French husband and I, married then six years, left the Midwest for France again and settled into a tiny apartment on Boulevard Raymond Poincaré in Juan-les-Pins. Our building was a couple of blocks from the sea, fifteen minutes walk past Le Hemingway Bar and another five to the Villa St. Louis, now the Hôtel Belles Rives, where you and Scott spent the summer of 1926. Still a relatively new mom (our kids, two and four years old), I struggled with feelings of profound isolation and restlessness. Though deeply grateful to be able to stay home, if it hadn't been for my sobriety, English-speaking recovery meetings in Antibes and Valbonne, and nearby parks: the Jardin Pauline (across the street) and the Jardin de la Pinède, as well as the beach, I'm not so sure I would have made it. Maybe that sounds like a luxury problem when some mothers don't even have access to clean drinking water, let alone parks or the sea but none of that should discount another person's experience. We have our karma to work out and can't completely understand what it's like to be a full-time mom trying to raise two young kids in a tiny apartment on Boulevard Raymond Poincaré in Juan-les-Pins, France until we live it.

There were many things to love about the Côte d'Azur—the sea, as you remember, Zelda, the wildness of Cap d'Antibes, Pablo Picasso in the museums in Antibes and Vallauris, Matisse's Rosary Chapel, Marc Chagall's grave, and James Baldwin's presence in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Éze and old Nice, the Oceanographic Museum in Monaco, the breathtaking Massif de l'Estérel, the rocky beaches in Agay, Cocteau's Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Jérusalem in Fréjus—but the traffic jams, the excess retirees, and not enough open roads and nature began to push us out.

Cap d’Antibes, photo credit: Jody Kennedy

It's not clear how far you took the affair with that French aviator you met in Saint-Raphaël (where you were bored and lonely waiting for Scott to finish writing The Great Gatsby) though it did go far enough for you to ask for a divorce, which Scott refused and you didn't push. Why didn't you insist? Maybe part of you knew that the French aviator couldn't save you like Scott couldn't have saved you but still, you weren't quite ready to consider the possibility that in the end there is nowhere to go but within. The grass is never greener, wherever you go there you are, relationships built on mutual or exclusive drunkenness are generally doomed from the start.

(One of you needs to be courageous and leave.)

My husband's job at the shipyard where he'd been working on the Île Sainte-Marguerite ended and I was more than happy to leave Juan-les-Pins. From there, we moved to small hameau near Saint-Tropez where my husband had a new contract installing cabinetry in villas owned by wealthy Russians. I wasn't sure which was worse, a tiny apartment on Boulevard Raymond Poincaré in Juan-les-Pins or the upper apartment of a tiny house in the middle of vineyards and olive trees near the foothills of the Massif des Maures, a small mountain range that runs from Hyères to Fréjus.

“I hate a room without an open suitcase in it—it seems so permanent,” you said. After you and Scott married you roughly lived in: Westport, Connecticut; New York City; Paris; Saint Paul, Minnesota; Great Neck, Long Island; Paris again; Saint-Raphaël; Rome; painting classes on the island of Capri; Paris again; Juan-les-Pins; Paris; Wilmington, Delaware; Montgomery, Alabama; Baltimore, Maryland; Paris; the Clinic Malmaison (near Paris) after your first mental breakdown; Valmont Clinic in Glion, Switzerland; Les Rives de Prangins Clinic in the district of Nyon, Switzerland; Montgomery (again); Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore; Sheppard-Pratt Hospital in Towson, Maryland; Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina; and after Scott's death in 1940, you went between Montgomery and Highland Hospital where you ended up dying in that fire on March 10, 1948. You were buried next to Scott in Rockville Union Cemetery, Rockville, Maryland before both of you were moved across the street to St. Mary's Catholic Church Cemetery. (Did you ever miss not having a more traditional lifestyle? A white picket fence and a garden? A place for Scottie to call home?)

Though there were no serious conflicts in my marriage, I still struggled with a long-standing modus operandi of being attracted to and wanting to sleep with certain men who were either good-looking and/or made me laugh. My French aviator du jour turned out to be a dreadlocked French-Algerian boy who was working on a property down the road. In my imperfect French, I spoke with him about Bob Marley, Haile Selassie, and the Rastafarian community in Shashemene, the Ethiopian town where my son was born. I took extra strolls with the kids during the day and when my husband got home from work, I made excuses to leave early on my walks just to get a glimpse of him.The only thing that ever came of the affair though was me feeling incredibly desperate and foolish for having had such a serious crush on someone who was not only married (with kids, too), but almost half my age. It reminded me of those men who prefer young girls to women of their own generation and how I'd always resented that, especially being on the receiving end when I was younger unless the attention was from a man I admired. But now, since about post-thirty-five, I've clearly noticed (with mixed feelings) being passed over by that objectified gaze. Didn't you, Zelda, as Nicole Diver, in Tender Is the Night, fight with Scott i.e. Dick Diver about the same thing? Are we loved for our fresh bodies or for our beautiful minds? Can we be equals with men or will that always and forever threaten the status quo? And conversely, are we loving men for their bodies or are we loving them for their minds? “Thou art the thing itself. Unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art,” (alas) said King Lear.

Zelda in Ballet Outfit: Photograph by CSU Archives / Everett

Saint-Tropez wasn't our style, though there was enough to like about the region—less traffic and more nature and easier for the kids and me (i.e. more space to play outside), the silence, especially at night and the stars and the mimosa trees blooming in spring, the long walks alone in the foothills of the Massif des Maures with a neighborhood dog, a lonely Jack Russell terrier I named Oscar who had taken a liking to me (the feeling was mutual), the castle ruins in the village of Grimaud, the Musée de l'Annonciade and an English-speaking recovery meeting in Saint-Tropez—it became clear though when we visited the local crèche to sign our daughter up for preschool that “St-Trop” and environs wasn't going to be our destiny. I dreamed of living in a walkable city and, like my husband, for more varied artistic and cultural offerings.

“Goofo, I'm drunk,” you said to Scott when Scottie was born. “Isn't she smart—she has the hiccups. I hope it's beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool.”

Most of the girls in the Good Girls Bad Girl's Club ended up having mental breakdowns (is that the price some of us pay for trying to stay fools?). Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath died by their own hands, my maternal grandmother lived to an unhappy fifty-six, and my paternal grandmother, said to be a handful, who I never knew and whose story I'll never fully know, disappeared completely from my father's life when he was thirteen. Though I never received an official mental illness diagnosis, my moods swung from out of control to severely depressed. A culmination of small and not so small breakdowns ended with me quitting drinking at twenty-three and then another breakdown with me suicidal at eight years sober which resulted in the going off of all medication and being baptized in the Catholic Church.

“…If the person doesn't listen to the demands of his own spiritual and heart life and insists on a certain program, you're going to have a schizophrenic crack-up. The person has put himself off-center. He has aligned himself with a programmatic life and it's not the one the body's interested in at all. And the world's full of people who have stopped listening to themselves.”

On a recent vacation to Aix-les-Bains, and thinking of you, I'd planned to visit Annecy where you and Scott and Scottie spent two weeks in July 1931. Scott picked you up from Les Rives de Prangins Clinic in Switzerland and the trip would turn out to be one of happiest for both of you—so much so that you never wanted to go back Annecy and risk ruining those memories. I'd never officially been to Annecy except passing through some years back after visiting friends in Thonon-les-Bains. We ended up not going to Annecy this time either because I was afraid that in the crush of tourists and the oppressive August heat, I wouldn't be able to find you.

There are eleven online reviews for Les Rives de Prangins Clinic, now Prangins Hospital in Switzerland. With an overall rating of 2.5 stars, half the stars are just stars and the others, with commentary, mention that some of the nurses are impatient and rude unless nothing is expected or demanded of them, the doctors are often late, and it can be difficult to get a good cup of tea. Nevertheless, the grounds are spacious and lovely with ping-pong tables, checkerboards, and beautiful views of Lake Geneva.

Les Rives de Prangins Clinic, Switzerland: Photograph courtesy of delcampe.net

You had already written and published dozens of short stories and articles when you gave birth to your first novel Save Me the Waltz while a patient at Phipps Psychiatric Clinic in Baltimore. Scott was furious and accused you of stealing material he'd planned for Tender Is the Night. For whatever reason, you turned the manuscript over to him to be reworked and it was published in 1932 to lukewarm reviews. The book was written well enough but I came away wanting more, some truth, something deeper or more revolutionary. Why do we write? To exorcize demons? To win a knife fight? To be seen? To prove a point? You left an unfinished manuscript titled Caesar's Things. Does it hold the key to your life, I wonder? Does it unmask what was masked? Does it render to Caesar the things that are Caesar's; and to God the things that are God's[1]?

*

We kissed indiscriminately, collected ostrich feather pompoms, and wore retro dresses. Our beds were our kingdoms, our insomnia, and migraines, our asylums. We hid from school, from social engagements, from proper employment, from our children, our husbands, ourselves. We clung to memories of being mothered by our mothers’ (our mothers, our mothers: sweet, controlling thrift sale lovers) chicken noodle soup and cool thermometers. We pulled the starched Martha Stewarts, the pressed vintage percales up around our ears. We offered our eyes to the ferryman who ferried us slowly back through muted childhood, watery fetalhood, pre-Eden, pre-Big Bang before we tried to manipulate and stretch and breathe life into our stuffed animals and our dolls.

*

What do you do with a girl who drinks too much? Who gets furious and calls you a spoilsport and a killjoy when you don't want to go out to the bar or have sex half the night? What do you do with a girl who's jealous of other women (even your mother), of your friends, and of your artistic creations? Who slaps and taunts you, throws knives, pots and pans, and remote controls?

(You can take the girl out of the alcohol but you can't take the alcoholic out of the girl.)

You had a religious conversion at the end of your life, wore black and preached Bible verses on the streets of Montgomery. I had my own Joan of Arc period some years after being baptized at the Cathedral of Saint Paul and though I wasn't aware of it at the time, it was the same church Scott had been baptized in as a baby.[2] And my apartment (#8) at 1439 Grand Avenue was just a mile or so due west from Scott's third-floor room at his parents’ house on Summit Avenue where he furiously rewrote This Side of Paradise with you in mind. And when the story was accepted for publication, you said yes to marriage and the rest is history.

Save Me the Waltz Original Book Cover: Photograph courtesy of Raptis Rare Books.

“Self-portrait” (painted in watercolor during one of your hospital stays, probably in the early 1940s) was an image I just couldn't get out of my mind. There, I imagined a sublimation of self, of you and of all of us, a twisting of something beautiful into something ugly, something warm into something cold, something innocent into something evil. You had a dream of being free once, of breathing underwater, of taking the wheel, of dancing in the Russian ballet, of mothering and loving and gentleness. Is this really how the Jazz Age ends? With us trying to recapture an illusory golden epoch? When girls were girls and boys were boys, and black was black and white was white? And all of the rest of us, witches, mystics, androgynous and ambiguous stayed hidden in the shadows? Tell me, how does your brave new world look now, Mister Death?

“Down here,” you wrote a friend after Scott died, “the little garden blows remotely poetic under the voluptes of late spring skies. I have a cage of doves who sing and woo the elements and die.[3]” You were living with your mother in Montgomery then and had been given the green light to leave Highland Hospital but you chose to return, you hadn't been feeling well, you—

*

There was a great fire come down from East Egg, come down on the backs of Hestia and Chantico and lo also the lady in Ibsen's and Munch's The Lady from the Sea. We cried as we watched East Egg burn, watched Montgomery burn, watched the smoke rise up in the West as from a campfire in the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains and lo from the ash we saw a dove rise and beheld in amazement Scott coming down on a cloud. Scott, Scott, Scott, Darling, Goofo, beautiful golden-haired boy and you, Miss Zelda (Everybody) falling over yourself to meet him.

*

I started this letter angry at Scott and wondering how you could have given so much and given up so much. You and Scott were so young when you met (twenty and twenty-four) and as I went back through your lives, so knotted and fused, I slowly began to understand that you and Scott were two sides of the same coin, the animus and the anima playing out its old, ancient game. So was it destiny or just common, garden-variety codependency? (Probably a little bit of both.)

Amazon created a series a few years back called Z: The Beginning of Everything based on Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler. The final episode ends at you newly pregnant with Scottie and though I don't believe the series did you justice, it is a testament of just how deeply the story of you and Scott continues to resonate with us. In America, we still like to glorify flappers, but it seems to be less about writers and artists now and more about reality TV stars. I'm guessing we'll probably always be more enamored with the glamour but maybe not so much the happily ever after. Thinking of you, Zelda, and hope you are well wherever you are.

Love always,

Jody

Edvard Munch, “Lady from the Sea,” 1896: Image from Wikimedia

[1] Reference to Romans 13:1

[2] The Cathedral of Saint Paul was inaugurated at its present location in 1915. Scott was baptized at the previous location on Saint Peter and Sixth Streets in downtown Saint Paul, Minnesota.

[3] Andrew Turnbull. Scott Fitzgerald, le magnifique (Robert LaFont Paris, 1964). 330.

Jody Kennedy's writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Juked, DIAGRAM, Tin House Online, CutBank's Long Way From, Long Time Since and The Woodshop, Electric Literature, and elsewhere. She lives in Provence, France. More at her website: jodyskennedy.wordpress.com.

Visit Jody Kennedy’s previous work at CutBank:

* * *

Long Way From, Long Time Since features letters written from writers, to writers, living or dead. Send us your queries and inquiries, your best wishes and arguments, and help us explore correspondence as a creative form. For letter submission guidelines, visit our submissions page or email cutbankonline@gmail.com for more information.

Referenced in the text:

Zelda Fitzgerald. Save Me the Waltz. (Scribner, 1932). <http://fitzgerald.narod.ru/zelda/waltz1.html>

Footage File, “F. Scott Fitzgerald,” YouTube Video, 0:23, January 17, 2011: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qy9vXKKPeBk?rel=0&w=560&h=315

Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth (Episode 1, Chapter 12). <https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Joseph_Campbell> [14 September 2018]

E.E. Cummings. “[Buffalo Bill 's]” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47244/buffalo-bill-s

Andrew Turnbull. Scott Fitzgerald, le magnifique (Robert LaFont Paris,1964). 330.