A Q&A with Visiting Hugo Writer Stacy Szymaszek

By Tommy D’Addario

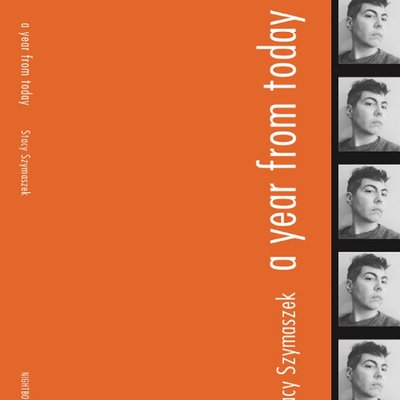

Stacy Szymaszek’s most recent book, A Year from Today, exemplifies a verse record, or a poetic diary, which documents one year of the writer’s life in stunning verse. She does not shy away from imparting details in it, chronicling everything from her passing thoughts to the day-to-day activity of a life in New York City. Stacy and I met frequently in person to discuss the book and conducted the interview via email.

Stacy Szymaszek will be reading poetry on Friday, Oct. 26, 7 pm. Click for details.

Tommy D’Addario: The more I read, the deeper I become absorbed in the details of a year in your life. How does it feel knowing that readers have access to your diary of sorts? Is there a reticence, a holding back of certain details, that comes with writing journal poetry?

Stacy Szymaszek: I haven’t kept a proper diary since I was in high school. Writing in a book with “a lock” isn’t compelling to me - in fact I think it reminds me of profoundly desperate times when I had no one to talk to or listen to me. This book was conceived of as a book, a book I knew would be published. I naturally developed an idiom to write these journal books, a sense of what types of information I share and don’t share, so the editing could happen in the brain more than on the page. But one of the risks I wanted to take in this book, and Journal of Ugly Sites and Other Journals, is to include as much of myself as I could tolerate – and have it work formally and melodically.

TD: The presence of religion is threaded throughout the book, sometimes as imagery, other times appearing as an influence on worldview. The speaker repeatedly seeks her “Mystical Experience,” finds herself at bookstores to “haunt the religion section,” and states, “I’ll always go mystical / St. Francis over Hitchcock.” At one point, the speaker says, “I could read martyr stories all night / what a charge // “women who gave their lives for the church” // in an everyday theology.” In what ways do you find religion influencing your poetry, and how does one find this Mystical Experience?

SS: I think modes of self-discovery have influenced me even before I knew what poetry was. I was raised Catholic and went to Catholic grade school. I hated its authoritarianism, and by no means did I escape the notion that I might go to hell. The pressure to conform was so extreme. And I couldn’t really pass, though I tried at times, in order to give myself a break. Very draining. I didn’t have the language to talk about my difference. It was just in the air like an open secret everyone wanted to go away. I started reading self-help books when I was a young teen - I think psychology and the experience of years of therapy are a mode, an influence too. To answer your question, poetry is religious and devotional for me. And mystical. I’m defining a mystical experience as an altered state of consciousness where you come out of it knowing something new. Often for me it is actually seeing something new. So writing poems can sometimes alter me. I’ve had some sexual experiences that have. Now, as I’m spending time in the mountains of Missoula, I can feel the potential for reaching an altered state up there. I think an abundance of time alone is beneficial, where time starts to break down. Writing poems breaks down time. I’m inspired by Christian writers like Thomas Merton and the mystics who embody and value dignity, grace, passion, and unconditional love. As you can tell from the reading we do in class, I’m also influenced by Zen Buddhism and how it has manifested in the US in the work of poets like Kyger, Whalen, Ginsberg and Waldman. I need various paths to follow simultaneously. I’m not the convert type.

“Poetry is religious and devotional for me. And mystical. I’m defining a mystical experience as an altered state of consciousness where you come out of it knowing something new.”

TD: This project covers the span of an entire year. Why did you decide to omit dates from the journal?

SS: That’s such a good question! Honestly, it never occurred to me to use dates, so it wasn’t a decision to omit. I must have wanted to think of it simply in terms of 365 days. That was the only marker of time that felt relevant.

TD: Though there aren’t exactly 365 “sections” in the book (I know, I counted). Surely some of the content of multiple days elided into a single section here and there? If that’s the case, did content from all 365 days eventually find its way into the book in one form or another? Or, were some of the days of your life left unmentioned?

SS: Ha! How many are there?

TD: I counted 133 sections, but I’d leave a small margin (plus or minus a few) for error.

SS: Let me clarify that A Year From Today meant literally that. I would write for a year from the day I started. I didn’t write every day. Many days elide into one section, and many days are left unmentioned. It wasn’t that exacting. I did employ dates in Journal of Ugly Sites and Other Journals, but this book wanted to be a rolling cloud of time. I guess it could be any year, any day - the particulars change but I am still me, navigating the cards I was dealt.

TD: Often the speaker approaches the text as an opportunity to defend poetry’s function in our world, despite the fact that “there is nothing harder to raise money for than poetry,” and “there are always plenty who will say it’s dead.” How do you maintain hope for poetry’s continued relevance in spite of these views?

SS: Hope can feel so passive, but I have it because I keep doing it, writing against the odds (exhaustion, lack of time, anxiety…) and there are so many poets I admire who keep writing interesting and exciting work that challenges the status quo. I surround myself with those people. And my sense of lineage, which includes an understanding of history as well as the importance and particularity of the present, helps me feel like I have a place within it. What do you think as a young person pursuing the study of poetry?

TD: I know there are plenty who say poetry is dead, but I just don’t believe it. The fact that you and I are discussing poetry now says something. I also believe the poem propagates itself. I read your book and it inspires me to create my own poems. This poetic spirit multiplies exponentially through the world: there are always people who will connect with a poem they read and want to turn that feeling into creation; there are always people who will want to study poetry, despite the awareness that they won’t be able to financially support themselves on writing poetry alone. I also think it’s crucial to poetry’s survival that it adapts through evolution, much like a biological species. A Year from Today is a perfect example of this. Your book is unlike other books of poetry I know, as it formally challenges the conventions of the genre through its journal-in-verse approach. As long as poets continue to innovate and explore the possibilities of verse, and as long as readers find these books in their hands, the art of poetry cannot be dead.

SS: I want to add that people also continue to read poetry. The NEA figure on adult readers of poetry in this country is 12%, which is up from 7% in 2012. I’ll also add that I’ve been running really successful reading series (dynamic audiences and poets) for most of the past 20 years, so I’ve had no cause to ever question the life of poetry or its relevance. I agree with what you’re saying about connection leading to creation. I’m so happy that you’re spending time with my book. I believe that my own work must evolve and adapt. Similar to running The Poetry Project - I had to make sure the organization stayed nimble enough to respond to the times, feel relevant to young people who were discovering it, as well as the elders who founded it and have supported it for decades. I abide by the idea that you have to let the language lead you, and if you do that, you end up in surprising and very lively places.

“I feel like I am part of a lineage. To me, this means that I’m an active poet among others I feel connected to aesthetically and/or emotionally, and I am interested in the history of poetry, and what needs to be passed on through me.”

TD: You mentioned your poetic lineage, which I find fascinating. Here’s a big question: What is a poetic lineage, why might this be important, and how do you describe your own?

SS: The way I think about poetic lineage as a concept has been greatly influenced by the poet and also former director of The Poetry Project, Anne Waldman. And through her informal mentorship it has been more than a concept for me - I feel like I am part of a lineage. To me, this means that I’m an active poet among others I feel connected to aesthetically and/or emotionally, and I am interested in the history of poetry, and what needs to be passed on through me.It’s a mode of awareness. I think modes of awareness are important and knowing one’s history is crucial. Some really evil-headed shit capitalizes on people’s collective amnesia. Anne says in one of her essays - imagine you are not alone. It’s only this vocation that has ever provided that sense of company for me and I think many others feel this way. I don’t really describe my own lineage in a particular way, though I will say I worship at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church.

TD: You’ve just touched on so many interesting points! I’d like to dig deeper into these modes of awareness. What, in the history of poetry, do you need to pass on? It sounds like we’re talking about a sense of responsibility that comes with writing poetry.

SS: I carry the responsibility of poetry in a very specific way. It’s the responsibility to maintain the ability to respond, to create work and form relationships from that place. It’s a determination toward care. It doesn’t carry the pressure of being responsible for the fiscal health of an organization, but that said, I always think of something Robert Creeley wrote in “Philip Guston: A Note.” “Care, it seems, comes from several words, among them the Anglo-Saxon caru, cearu(anxiety) and the Old Saxon kara(sorrow).” I’ve been chewing on this one for many years! In my role as cultural worker, I make space for poetry. Being an educator is part of that, and as you know from our seminar, I have a strong interest in the long poem, time-constrained writing, form/ lineation… but my interests don’t matter as much as the fact that I’m creating a supportive space for you to figure out what you think through discussing and responding to work that is new to you and is hopefully opening up new pathways in your brain for your own writing!

TD: One of my favorite moments in the text: “my grandma says I got my talent from her [...] she just started writing poems / and says they are better than mine / because people can understand them.” What’s the story behind this one?

SS: Ha! Well, that’s the scoop. My mother gave her one of my books to read and of course she had no way in. Like many people, she wants poems to be accessible. I adore my grandmother and I was moved that she said this. It touches the sense of lineage as ancestry. She’s mine. And I’m hers. She thinks her poems are better than mine. She’s a diva!In fact, she had a beautiful voice and wanted to study opera when she was young but was forbidden. She was also forbidden to marry the man she loved because he was Irish, and she Sicilian. She always told me to free myself. We have a very interesting relationship. She’s very Catholic and I’m very gay but she makes her peace with it because, I suspect, she sees herself in me. One of my favorite things about her is that, for the past 25 years, when I say goodbye to her, she says “this is the last time we’ll see each other.” She’s 98 and has just been diagnosed with congestive heart failure, so when she said it in August, I thought, oh she might be right this time.

TD: I’m sorry to hear about her health. She sounds like a beautiful person! It’s great that she can reconcile her faith with your sexuality since so many people find tension in that. That tension runs throughout your book, too, and it seems to conflict with others and yourself. You write, “I live a circumspect life in some ways [...] direct / effect of homophobes obscured” and “maybe it’s longevity that gives me / anxiety [...] what if I live 50 more years [...] no country / for old dykes.” Such poignant lines. And again, while getting a haircut: “I told the stylist / make it more gay / more important to distinguish / these things because let’s face / it we fall in and out / of favor [...] hatred repeats itself / a pleasure system as Sarah says / of homophobia”. What does this “pleasure system” mean?

SS: The Sarah in the poem is Sarah Schulman and she talks about homophobia as a pleasure system in her book Ties That Bind: Familial Homophobia and Its Consequences. She says “...homophobes enjoy feeling superior, rely on the pleasure of enacting their superiority, and go out of their way to resist change that would deflate their sense of supremacy.” So she proposes that it’s actually a source of enjoyment for them, not a phobia. Sick pleasure, I’d say. That moment in the poem where I want to look more gay is a refusal to assimilate and a refusal of the notion that just because gay marriage is legal, equal human rights have been achieved. That right, like any, can be taken away depending on the political reality of the time. Like many LGBTQ people, I went to NYC to experience meaningful difference between myself and other people, to find others like me, and to feel safe. The poetry world provided that for me to such an extent that when I am confronted with homophobia now I am taken aback. When I wrote “effect of homophobes obscured” I’m saying it’s not such a great thing to have obscured because we live in a homophobic society and its trash heap is always stirring the psyche. It’s a note to myself to not lose that awareness.

“I let most of the discomfort in.”

TD: Which brings us full circle to our modes of awareness, only this is a different mode of awareness: of one’s body, of one’s safety, of our psychological, political, cultural situation. How does poetry help you explore these modes?

SS: It was evident to me shortly after I started writing books that included documents of walking in New York City that one of the implicit challenges to me was to change my mode of awareness. My baseline awareness is like a radar monitoring how close people get to me or if anyone is moving erratically. Very lizard brain, a little dissociated, lost in my thoughts - ironically. I essentially was raised to believe that I was in danger because of my gender and sexuality. Not untrue, but it wasn’t balanced with anything positive. It was very “no future” and I really did spend my 20s living like I didn’t have a future. When I turned twenty-nine, I was like oh, this could go on longer than I thought. Then, I got my first literary nonprofit job. Genet said something about writing being what made him a person in the world. Writing gave me a positive relationship to the public, made me less internal. So when I was walking in New York - this would be ten plus years later - I had to recognize my default mode and discipline myself to notice the flowers. I also just started including whenever I felt like I was experiencing a micro-aggression or whenever I felt like I was becoming self-conscious, or whenever a memory came in - I let most of the discomfort in. I learned to make work that was emotional and outward in gesture, which felt and continues to feel important to me.

Stacy Szymaszek is a poet and an arts administrator/organizer. She is the author of the books Emptied of All Ships, Hyperglossia, hart island, and Journal of Ugly Sites and Other Journals (2016), which won the Ottoline Prize from Fence Books. She is a regular teacher for Naropa University’s Summer Writing Program and mentor for Queer Art Mentorship. She was, until very recently, the Executive Director of The Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church. She is currently the University of Montana Creative Writing Program’s Visiting Hugo Writer.

Tommy D'Addario was born in Detroit, Michigan, and has lived on both of the Mitten's coasts. He has worked as a barista, a university writing instructor, and a chef on a ranch in Wyoming. He's a second-year poet in the MFA program at the University of Montana. His work has appeared in Columbia Journal, Southern Indiana Review, and RHINO Poetry.