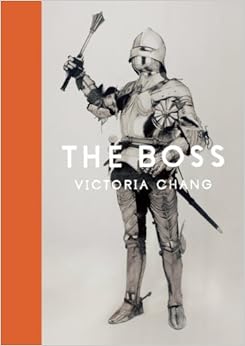

Victoria Chang is a poet and business consultant. She is the author of Circle (Southern Illinois University,2005), Silvania Molesta (University of Georgia Press, 2008), and, recently, The Boss (McSweeney’s, 2013).

Victoria Chang is a poet and business consultant. She is the author of Circle (Southern Illinois University,2005), Silvania Molesta (University of Georgia Press, 2008), and, recently, The Boss (McSweeney’s, 2013).

Victoria Chang was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1970 and raised in the suburb of West Bloomfield. Her parents were immigrants from Taiwan. She graduated from the University of Michigan, Harvard University, and Stanford Business School. She also has an MFA in poetry from the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers where she held a Holden Scholarship.

She worked for Morgan Stanley in investment banking, Booz Allen & Hamilton in management consulting, and Guidant. She lives in Southern California and works in marketing and communications. Her work has appeared in literary journals and magazines including The Paris Review, The Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, Virginia Quarterly Review, Slate, Ploughshares, and The Nation.

Q: For anyone who hasn’t read your most recent book, The Boss, how would you describe the collection?

A: I would describe it as an investigation of hierarchy, power, and loss of power/control. I would describe it as an experiment with sound and an exercise in word play to propel the poems forward. I would describe it as an experiment in losing control while writing the poems.

Q: The Boss has been called “obsessive, brilliant, linguistically playful” — if you had to pick three buzz words to sum it up, what would they be?

A: Obsessive, urgent, obsessively urgent.

Q: Have you had any reviews that you felt were particularly rewarding? Or come across any reviewers or readers you felt read your work in ways you did not intend?

A: Truly, beggars can’t be choosers. I will take any review by anyone and find something redeeming about the review. I think all the reviews that I have read so far have been very intelligent and that’s something I’m consistently surprised about. As a writer with a new book out, waiting for people to pay attention to your work, any attention in the form of reviews is agonizing—akin to standing naked on the side of the road with a cardboard sign that says, “review me” and a small bowl for spare change. It’s a pathetic feeling and state of being and one that I despise about post-publication. I sound ungrateful, but it’s hard to wait for something around the corner and even harder to read what people have to say about your work. I’ve been lucky this round with really smart readers like Seth Abramson at the Huffington Post, in particular. McSweeney’s has brought attention to my work in ways that other publishers could not.

Q: The Boss has an extremely distinctive voice that takes on a breathless urgency, often verging on obsessive, that really drives the book. Did you seek out this voice once you had begun the book or did it begin with the voice? What influenced or inspired your poetic voice?

A: So much of this book was about letting go of the process of writing, the process of picking up a pencil, thinking about something, and putting it onto paper. So much of this process was about the pencil moving by itself and pulling my hand and the brain along with it. The urgency inspired the poems and the voice reflects that urgency. I am naturally a very organic person but grew up and work in a more controlled environment. This book was about letting my natural organic self re-emerge and find itself again.

Q: It’s really interesting how the structure you set up for your poems allow you to surprise the reader in interesting ways when you deviate, satisfying and struggling against the rigid rules that mirror the stifling power structures your poems depict. What appealed to you about the uniformity of the shapes and stanza lengths of your poems? What was fun or frustrating about working with this structure?

A: What’s interesting about the structure of the poems is that they began with no structure. They were written in an environment of extreme heat while I was sitting in a car waiting for my oldest daughter to finish a Chinese language class in sweltering Irvine in the summertime. I sat in a parking lot in front of this same tree every Saturday for months and wrote these long-lined things that weren’t poems. The composition notebook formed the poems in that I just wrote until I reached the end of the page and they were in couplets for easier reading for me. McSweeney’s editors suggested the structural change and the quatrains that are staggered to help the reader since I didn’t use any punctuation. I really wanted the poems to mirror the loss of control I was feeling in my life at the time—I had a terrible boss, my father had just suffered a stroke and lost his language, and I had young children under the age of 5. I wanted the lines to spiral out of control in the way I felt my life was spiraling out of control. Add to that all the natural and man-made disasters, I just felt the world was ending.

Q: One of my favorite lines in the book comes at the end of “The Boss is a No Fly Zone:” “the boss’s boss’s boss just wants a fine/ job closes his outer lobe unless his son coughs/ like a sea at night,” because of the tender sadness of it against the more detached current of accusatory statements in the stanzas before. Was exercising restraint in deviating from (or adhering to) the form of the poems difficult during the process of writing this book? Are you someone who writes a poem and cuts half of it or more often revises by adding?

A: This book was written in 2 months and that’s it. I revisited some of the poems later and edited them and also perhaps wrote 2-3 more poems after that, but for the most part, this manuscript didn’t take long to write or revise. The poems in my composition notebook pretty much mirror mostly the poems that are in the book. My McSweeney’s editors made the poems crisper and cleaner and were so great to work with. Prior to this book, I was a heavy editor of my work and in my last book, Salvinia Molesta, took a lot of parts of poems and spliced them altogether. I enjoyed writing The Boss because it felt so much easier than my earlier writing process. I don’t want to write another way again—this could explain why I haven’t written a word since writing these poems 2 years ago. My other books weren’t finished until someone took them—that’s excruciating. I also have other manuscripts I abandoned along the way before The Boss.

Q: What inspired you to take on Edward Hopper as a subject?

A: I’ve always been obsessed with those paintings and look at them once in a while and I had written ekphrasis poems in my first book, Circle, off of some of those paintings. I looked at them again and noticed there were a lot more Hopper paintings that took place in office settings than I had originally thought and so decided to use the paintings to riff off of things and to use the paintings as a new entry point to these poems.

Q: How would you say the experience of being first generation has inspired your work? What ideas and reactions drove you to write this book?

A: I think being Asian American probably inspires and influences everything about me in my life. Not to whine, but it’s so hard being first generation. My sister and I recently had a discussion about how we felt like we weren’t taught anything by my parents—how to manage stress, how to communicate, how to deal with difficult situations, etc. I think my parents taught us what they knew but what they knew didn’t fit into this culture. We learned a ton from them, but some of the things, many of the things we learned were for a different culture. It’s hard to admit that I’ve spent my whole life re-learning how to exist in this culture. It’s been a rough road but an interesting one!

Q: You call into your poems power in many forms--from natural (earthquake), to divine, to human (the boss). Why did the idea of a boss speak to you?

A: Working in business for so long and having gotten an MBA from Stanford has allowed me to see into the world many poets might not see. I have also had my fair share of bad bosses. The good ones were so good, but the bad ones were really damaging. It also goes back to perhaps not having the tools or skills to manage tough situations, to know when to push back, to know when not to push back, to know when to move on. This boss that inspired this book was so passive aggressive and I spent years feeling like I was treated like a child and I could never figure out why this person wanted to control me so badly or disliked me so much. It took me a while to realize it wasn’t about me, it was about her hate of losing control over people and situations and the fact that all bosses probably have similar issues. And then I began to realize in many ways, we are all lost and have no power in some aspects of our lives. It’s just a state of human existence. This was all happening when so many other things were happening in the external world and everything collided.

Q: How much did your personal experience influence your poems? Have you ever been The Boss?

A: I spend my entire day working in business, with business people, thinking about business. It’s very interesting to me but I recognize the crassness of it all sometimes. I have been The Boss and I’d like to hope I’ve been a good one. You’ll have to ask others to verify! I’m also a leader in a lot of other aspects of my life in terms of volunteer work I do and I really enjoy leadership positions. I think working in a professional environment is difficult. All the politics, communications, problem-solving. Business is essentially constant problem-solving so there’s conflict all the time. And sometimes the people aren’t that great, but that’s probably true in the poetry world and academia too.

Q: If you could collaborate with any writer on a book of poems, who would it be?

A: Shane McCrae. He would drive me batty, but I would love every minute of it. Louise Gluck too, I think we’d make an interesting pair of somberness.

Q: If you could choose your perfect reader--the person you’d most want to find your book on a shelf or get it as a gift--who would it be? Do you have a particular audience in mind when you’re writing?

A: I have two ideal readers—one is the practicing poet, that person who reads poetry to learn about writing poetry. The other is someone who never reads poetry—that’s what McSweeney’s is great for—they have so many readers of literature that haven’t read poetry that are reading my book—I love that. Being on NPR Marketplace was great in that way too—all these listeners who don’t read poetry were engaged about poetry, even for a little while—I love that.

Q: How do you balance writing and working?

A: I don’t. I don’t write anymore. I just read books and try to stay on top of what’s happening in the poetry world. I heard Louise Gluck writes like that. I think for better or worse, that’s the way I will write going forward if I ever write poems again. Not caring if I ever write a poem again is liberating, absolutely freeing. I love that feeling. For the first time in my life, I feel untortured.

Q: What were the most fun and most frustrating moments of writing The Boss?

A: It was all fun writing it because it came quickly. The frustrating part was the 6 months after it was “done” and when I started doing the editing. It was light editing, as I mentioned, but I still tortured myself again and again reading that manuscript and beating it to death. The most fun was knowing that I was doing something different (from my old self) and being unsure what it would be, but enjoying that process. The other fun part was finally giving it up to McSweeney’s and saying, “You go at it” and knowing they would.