Interview with Andie Francis, author of CutBank's 2014 poetry chapbook

"I Am Trying to Show You my Matchbook Collection"

(Interview by CutBank Online Managing Editor Heather Jurva)

Let's begin with a pretty standard question: what is your writing day like? do you have any routines, etc., especially when you were working on your latest chapbook?

I wear lipstick. That, and I tend to write in isolation, away from distraction as much as possible. I’m a full-time teacher, so demands come with the territory. Sitting down to write during the academic year is a challenge.

I try to write-write in the morning, with my favorite coffee mug, before anything can supersede my intentions. Annie Guthrie, one of my poetry gurus, says we are always writing, even when we aren’t writing “on the page.” Annie’s idea keeps me going when I hit a rough patch. Even if I don’t have energy or time to face the substantial writing, I surround myself with language and art. I am constantly adding to my notes on my phone throughout the day. I keep a Pinterest with various boards for visual and/or conceptual aesthetics that inform my writing or thinking. I frame my teaching around language, and I get to hear teenagers read all day. I learn from where they inflect, stumble or giggle. I love to read new books aloud in one sitting to have the auditory experience of the book.

Speaking of, when I was writing my chapbook, I read Bhanu Kapil’s The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers aloud cover to cover. It took several hours. I read Kapil’s book, and wrote a substantial amount of my chapbook while housesitting for Professor Alison Deming who lives in the shrub desert, and another portion while at the Writers’ Conference in Port Townsend, Washington. My chapbook deals with retreat, and was written in retreat, but for the most part, my writing isn’t relaxing or a withdrawal. I don’t want it to be. I’m grateful for the time I spent in Tucson and Washington as I forced myself to do the necessary mental work. I sat with myself for a long time, in a sort of desolation. In both of these cases, I mined myself for the stuff that I had been writing in my head for a while and tried to grapple with it on the page.

Where do you find your inspiration? Specifically, can you speak to the impetus for  "Matchbook?" Who do you read? What have you been reading lately? Do you generally read while in the midst of a project?

"Matchbook?" Who do you read? What have you been reading lately? Do you generally read while in the midst of a project?

My inspiration comes from friends and teachers, the natural world, and, of course, from language, which is all of these things at once. I look and listen. A lot. I have always been fascinated with “writers” and “artists” as a subject, probably because I never gave myself permission to “be” one until recently. I pushed this side of myself away to stabilize what I thought would be an accepted or easy path. I lacked confidence in my abilities until I was admitted to the graduate summer Writers’ Workshop in Iowa City. That workshop gave me the confidence I needed to apply for graduate study and pursue my poetry for real.

I Am Trying To Show You My Matchbook Collection started in the last semester of my MFA program at the University of Arizona. I took a workshop with Ander Monson who asked us to write a chapbook as part of our final project. Initially, I resisted the project because I didn’t know how it could be possible to write a chapbook while revising a thesis manuscript at the same time.

I figured a way to develop two books simultaneously. I would write about the summer between my first and second year in my MFA. Everyone I knew was going through a breakup or quitting smoking or falling onto a cactus. I wanted to write a chapbook where these ordinary events were promoted to extraordinary because a part of me decided this wasn’t just a summer, but the summer. I also was in the midst of a shift in my work, and Ander’s class was the perfect opportunity to experiment in terms of form and process.

I always read in the midst of a project. I use other artists as a palette for my work. Maggie Nelson, Lyn Hejinian, Bhanu Kapil, Jane Miller, Joshua Marie Wilkinson, Carmen Giménez Smith, Michael Palmer, Adrienne Rich, C.S. Giscombe, Kazim Ali, Nick Flynn and Dora Malech always have a spot on the top shelf.

I’m still crushing on Jane Miller’s Thunderbird. I bought it when it first came out, and I continue to return to it. I always walk away with new feelings, especially about myth, when I read Jane’s work. Polina Barskova’s This Lamentable City and Brian Blanchfield’s A Several World are bedside studies. I also just started reading Sara Jane Stoner’s Experience in the Medium of Destruction and Karyna McGlynn’s I Have to Go Back to 1994 and Kill a Girl.

I am also mesmerized by the ways you play with form, especially in the poems that merge previous poems. Do you write the three individual prose poems first and then assemble them into stanzaic form? Or do you write the stanzaic first and then deconstruct it into its component parts?

While writing these poems, I was thinking about Hannah Weiner’s opposing dictated words in her Clairvoyant Journal and “questions of order and disorder, capacities and incapacities,” as Lynn Hejinian’s discusses in her collection of essays, The Language of Inquiry. I was also underscoring everything with Ron Silliman’s The New Sentence. My process was mostly just an experiment with language, form, and chance.

I think of these poems as transliterations. I started with a lineated form. They were written line by line in the sense that each line could stand alone. I was trying to get close to a finite memory by working with tercets. I wanted to confront the tradition of the number three. I wanted to see which line, first or third, or the liminal second, would or could be more “accurate.” Or which line would open narratives, either linguistically or semantically.

I wanted to know if all lines are created equal. I wanted to learn how lines could lean on or repel one another. I wanted to discover how the lines’ inherent relationships changed when placed into new formal families (i.e., prose poems). Right now, I still get into moods where I want to deconstruct these poems – put them into new families. Maybe work with even numbers (e.g., quatrains) to see how this changes the experience.

Thematically, I've noticed you work quite a lot with the body - pain, consumption, and so on. Can you speak to that creative impulse? "Matchbook" seems to read as anchored pretty firmly in place - what role does place play in your inspiration and your writing process?

In writing about the body, I use language that feels more vital to me, and because the language is immediate, I feel more alive. I want to feel alive, you know, exhilarated, even when I write. When I make the commitment to remove myself [from the classrooms, parties, restaurants, and bars] so that I can write poetry, all that’s left is the body and the word. My poetry is not a break from life, but a way of being continuous with it. In Tucson, I am very aware of my body. The desert does that to you. If you don’t get valley fever, you get a staph infection, shingles, a rattlesnake bite, a rock under your skin, dust in your eyes. You fall on a prickly pear. You walk home in a monsoon. You scream at the top of your lungs from a prehistoric rock. You walk around in the dark unnoticed because of the streetlight ordinance. The body is inseparable from place because it has been placed.

Finally, can you offer any advice to a reader who admires your work? What do you like most about publication as a chapbook?

I Am Trying To Show You My Matchbook Collection begins with this epigraph from Bhanu Kapil: “Even this sentence is suspect: indefensible; potentially, already, rewritten.” In one way, Kapil is talking about language as deficit. Once the eyes have glimpsed the sentence, its other versions become lost. Potentiality is sacrificed. No matter how I write a line the first time, when given another chance, the language will re-decide itself. The reader should know that the edifice of the language is going to change, so I think it’s important to be skeptical of that initial context, to not ally one’s self to the language or form. It’s okay, of course, to read it any way. There are risks, regardless.

I started this chapbook as a chapbook. A lot of my poetry before this was about ends, about making ultimate decisions for the line. I was destining those poems. Here, the poems destine themselves, and re-destine, and I plan to carry this through in a sequel set in the New Jersey Highlands with the same speaker and “characters.”

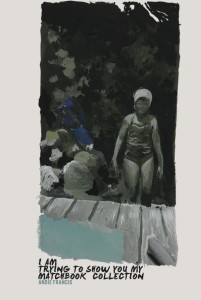

I like how a chapbook fits in my purse. How I can bend the cover back once, and it will stay open. I love the cover of this book, a painting called “End of Summer” by Noah Saterstrom. To me, the whole chapbook feels like I’m yelling down into a well. I don’t know if I’m yelling to that summer, the summer, all summers, but these poems echo back.

Andie Francis is the author of the chapbook, I Am Trying to Show You My Matchbook Collection (CutBank 2014). Her work appears or is forthcoming in Cimarron Review, CutBank, Fjords Review, The Greensboro Review, Portland Review, and Timber.