A Conversation with John C. Ryan

By Lauren Frick

I first encountered John’s work in The Language of Plants during an independent study. I was struck by the astute agency John discerns in plants. John relays an understanding of plant voice and the way in which plants communicate as nonhuman beings in the world. This is of particular interest as we navigate a more sustainable coexistence in the world. My professor, Garin Cycholl, previously had heard John speak and he recommended that I connect with John. In the wake of COVID-19, John and I conducted this interview over email in order to best accommodate each other’s schedules and pertaining time zones, as he was in Indonesia and I in Northwest Indiana. Over the course of June, we corresponded as John shared various pieces on Aboriginal poetry and discussed how COVID-19 influences human understanding of nonhuman agency.

Lauren Frick: Why did you start writing about plants and the natural world? Was there a certain time or event that sparked your interest?

John Ryan: I began writing about plants and the natural world in my teens. I grew up on several acres of land in a semi-rural part of southern New Jersey. I recall lady slipper orchids in the spring, and held imaginative conversations with oak trees. There was a creek across the street with skunk cabbage plants. Deer frequented the area. About five miles from my house, there was a reservoir with a circular path around it that I enjoyed walking in all seasons. However, to build this reservoir a large section of forest and several small homesteads were drowned. I took a photo I called “The Drowned Forest” (of dead trees around the reservoir) and submitted it to the high school “lit mag” (annual creative writing magazine). I also wrote short opinion pieces for the local newspaper about the pitiful state of heritage conservation in the area. I guess I was a young activist at that time.

LF: As you mention in “In the Key of Green” in The Language of Plants, in order to acknowledge plant voice, you have to remove your own. What have you found to be the best means of thinking to remove human bias as you write? For instance, the following lines in “Nocturne:” “Devoted I am to this mode, being / an ascetic in a dirtless crevice, / bivouacked to a Gondwanan terrace, / disciplined I am to disagreeing.”

JR: I think that’s a perceptive interpretation of “plant-voice”—to acknowledge it, one must get around one’s own voice, otherwise the echo chamber effect becomes inescapable. Human bias is to some extent unavoidable. As a human interloper in a natural environment, I necessarily perceive plants and other life forms through my own capacities of sensing, apprehension, reasoning, intuiting, and so on. However, the mistake is to assume that I am the only perceiving subject taking part in the encounter. Sense perception is inherently dialogical. Quantum theory reinforces this idea. To see is to be seen; to affect is to be affected; and so forth. The other faux pas is to assume that only my voice matters, and moreover to assume that it is only my voice. The world is intrinsically polyvocal (many-voiced) and heteroglossic (many-tongued). My “voice” is not merely mine but an emergent quality of being in relation. I’ve written the following passages recently in an analysis of Aboriginal Australian poetry:

“In its normative anthropocentric framing, the term voice denotes the articulations produced by the human larynx, mouth, tongue, and lips to communicate in discrete tones, registers, and accents, making the presence of the individual known to other beings. To assert that plants have voice(s)—or, at least, that they should not be denied voice—might seem outlandish or specious. Of course, anatomical sense tells us that vegetal life lacks the mechanical structures necessary to vocalize as humans do. For plant-voice to become tenable, then, we must think about voice differently— …In perceiving sound—that is, in listening—plants modify their behaviors in response to acoustic stimuli impregnated with vital information about pollinators, herbivores, frugivores, weather, soil conditions, and water availability (Khait et al. 134). Studies of plant-to-plant acoustic communication, moreover, suggest that plants heighten sound emissions when confronted by drought, flooding, fire, grazing, pruning, infestation, and other environmental stressors in order to prime the chemical defense responses of the neighboring plants with whom they communicate (Khait et al. 137).”

Attuning to the voice(s) of plant nature is one of the urgent tasks of poetry. The best means of removing human bias when writing, in my view, is to approach plants sensorially and as fellow-beings. Their voices are not to be heard as sonic utterances following linguistic rules but have more to do with semiotics, as the complex operation of signs in the environment. The voice of the plant could be pheromonal, or, as the Medieval doctrine of signatures claims, physically mimetic of something else of value and meaning. The faculties of taste, touch, and smell also help me to bypass the cogitating, bifurcating mind and enter the realm of nondualistic somatic interrelation, or intercorporeality. The sonnet “Nocturne” is written from the perspective of the gorge-dwelling plant. This sonnet is part of a series of poems that I physically composted (buried in the earth near certain plant species) and removed at regular intervals to “read” what had been written by the earth-plant-system. The reasoning behind this is detailed in my chapter contribution to Geopoetics in Practice.

LF: Is there a topogorgical poetry of New Jersey?

JR: Yes, we might think of the Appalachian Trail corridor of Northwest New Jersey where the ancient geological landscape draws perception downward into valleys and gorges rather than upward (towards the sublime) or over (towards the picturesque). But, then again, it depends on how one wants to define the terms “topography” and “gorge”. There are in fact micro-topographies everywhere, even within the human body and mind.

LF: What informs the shape of your poems in “tree: 5 sonnets?” What is your place as the writer in the poems? Do you feel as if you are speaking for the trees or allowing the trees to speak?

JR: I prefer to think that I am allowing the trees to speak for themselves—or for us to speak for ourselves. I hope to give the trees, and myself, a medium for speaking. I’m not completely comfortable with the idea of speaking on behalf of nature because I cannot guarantee that I know nature’s or a plant’s language. However, I need to presume that the plant has a language in order to not fall into the trap of linguistic imperialism or, worse still, ontological nihilism. The poems certainly have organic shapes. They were buried for a period of time in the ground next to the species that figure into the poems. Some of the earth’s own “editing” affects the sonnets. Of course, the literary traditionalist would scorn the use of “I” as pathetic or affective fallacy, or an overly romanticized attempt to “hear nature’s voice.” But, for me, the shift is powerful because it flies in the face of such theories that are often divorced from the earth. Somehow the simple use of an “I” that simultaneously is me but not me, is irreverent, just like the plants themselves, watching, observing, giving feedback, mocking, contesting, resisting, all the time, and usually we’re not even aware of it (or them).

LF: In what ways do you continue to be influenced by Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter? Bennett writes, “It is futile to seek a nature unpolluted by humanity, and it is foolish to define the self as something purely human.” How has her understanding of vital materialism shaped the way you think about nonhuman entities?

JR: I appreciate her idea of “vibrant matter” within the context of new materialism and posthumanism but that’s where it stops for me. Essentially new materialism is an academic repackaging of what Thoreau and the Transcendentalists raved on about in the 1800s. And, then later, what the Beat Poet generation found inspiration in. I have been much more influenced by Indigenous World writing and, in particular nowadays, Aboriginal Australian poetry. Nonhuman entities are very much living agents in their own right in many Indigenous cosmologies. There I find an unproblematic undifferentiation between self and other. Plants, in particular, are often attributed powers that vastly exceed the limited human capacity for dull thought patterns.

LF: What particular aspects of Bill Neidjie’s work have impacted your own research, thought, and creative work?

JR: I appreciate Bill Neidjie’s seamless movement between human, animal, plant and cosmic subjects through his recurrent use of the pronoun “e”. This pronoun, used widely in Aboriginal English, is radically inclusive of all subjectivities: plant, human, animal, cosmic, terrestrial, etc. His narrative writing really shows us how all beings are profoundly interconnected.

LF: Climate catastrophes tend to evoke a wealth of emotions and feelings. How have the wildfires in Australia shaped your writing?

JR: Being a fairly peripatetic person, and on short-term academic contracts, I regret to say I haven’t physically been in Australia since December 2019, when the fires were just starting. But that’s probably been better, as I wouldn’t have been able to handle seeing those beautiful ancient Gondwanan forests burn and all the rare plant communities, not to forget the fauna, reptiles, and insect life, disappear. Climate catastrophe, acutely in Australia, is an extension of colonial occupation and Indigenous dispossession. Aboriginal Australians have lived on the continent for more than 60,000 years. While some research attributes megafaunal extinctions to Aboriginal overhunting, the reality is that to live in the same place for 60,000 years requires immense knowledge of how to do so in balance with nature and in cooperation with other humans. So, for me, thinking about my writing about Australian flora since the bushfires, the ideas of postcolonial critique and decolonial praxis take on much more significance.

LF: Similarly, how has Covid-19 influenced the way you think about the natural world and your thoughts on nonhuman agency? Do you think it is the writer’s responsibility to create a viable space for the human being in the Anthropocene?

JR: In many ways, the Covid-19 pandemic has forced humankind to think more carefully about our place on the planet—that we share the earth with all sorts of life forms in a radically interconnected way. Yet, nonhuman agency asserts itself all the time, not only in situations like this. To breathe the air at this very moment requires the agency of trees and other plant forms in breathing back. We’re in constant dialogue, with all life, without even being fully conscious of the true extent of our embeddedness. I believe good writing can supply a vibrant space for imagining possibilities for future cohabitation of the earth. Yet, sadly, much writing, even nature writing, still subscribes to an overly anthropocentric outlook that puts human emotion, transcendence, enlightenment, awakening, pleasure, feeling, dreams, hopes, aspirations, etc. at the forefront. The power of poetry, in my view, is its capacity to enable us to see ideas such as “voice” beyond the human frame. Prose can do this too, but poetry is especially well-equipped, due to its intensity and mutability.

LF: In “Narratives of Nettle” you describe Nettle as a companion species. How do plants like Nettle and other invasive species push against or go along with human progress? Do you think Covid-19 will function in a similar way as it continues to shape our lives?

JR: Nettle is a quintessential plant villain that has been demonized yet reflects back to us our own foibles and excesses. I can share with you an article that I have written about literary representations of nettle. Invasive species such as nettle are manifestations of the limits of human progress. There’s no doubt that Covid-19 will continue to haunt the margins of our collective consciousness, just as nettle does.

LF: Do you think it would be possible for a human being to regard the coronavirus as just one other aspect of nature like human presence?

JR: Certainly, ecocriticism, ecopoetics, posthumanism, and the environmental humanities provide a robust theoretical framework for thinking about viruses and other organisms as aspects of nature. The coronavirus reminds us that we share a planet with other humans as well as with myriad nonhumans.

LF: How have your studies influenced your diet? Do you see food differently or more or less objectively?

JR: I try to eat “low on the food chain.” But I also adapt to my surroundings. For example, I have been living in Surabaya, Indonesia, since February of this year. During this time, I haven’t stepped in a car or taken a ride in a motor vehicle. I’ve relied solely on walking from place to place to get food and other supplies. Petrol free is a good feeling, mostly. Usually I look for fresh produce at small shops where much of the fruit comes from surrounding agricultural areas. But, in the supermarkets, there is papaya from California, which seems ridiculous. What a long way for papaya to go, and only to arrive in a tropical environment where its friends are plentiful and cheap! I’d say that my studies have forced me to become very aware, at all times, about dietary choices. Diet is not something to be taken granted, especially above a certain age when your body is less able to metabolize substances like sugar, et al.

LF: Has COVID-19 impacted people’s sense of human progress in Indonesia?

JR: Many younger people in Indonesia see COVID-19 as a manifestation of human negligence of the biosphere. For one writing assignment, I asked students to record their observations of life in the coronavirus era. Many wrote of the return of nature to urban spaces normally crowded with people. There’s a budding environmental ethic in Indonesia, exemplified by the eco-pesandren movement (Islamic boarding schools with environmental sustainability programs).

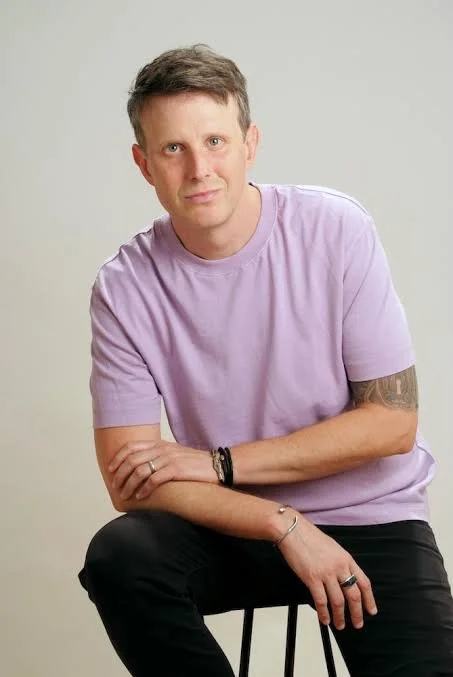

John C. Ryan was born and raised in New Jersey and has completed various postdoctoral research fellowships at universities in Australia. He is an Adjunct Associate Professor at Southern Cross University, Australia and currently resides in Indonesia. Ryan’s work focuses on the natural world, incorporating a perspective and understanding that grants nonhuman life its own agency. Ryan is an editor of The Language of Plants which features his piece “In the Key of Green?” that examines such relationships, as does his piece “Writing the Lives of Plants: Phytography and the Botanical Imagination.” He also has various other works, like “Narratives of Nettle,” that explore the vast impact colonialism has on the environment and how it has shaped human constructs of the world. His work is especially poignant as we consider the Anthropocene and ways to value and connect to the natural world. In “In the Key of Green?,” Ryan stresses that “poetry is a means of listening to and expressing plant voice as potentiality,” pushing the reader to consider the agency of the non-human world through poetry. Ryan’s works explore the understanding of how colonialism has severed Indigenous relationships with the natural world and assisted in the destruction of a livable world. His forthcoming collection Seeing Trees: A Poetic Arboretum, co-authored with Australian poet Glen Phillips, will be published by Pinyon Publishing in August 2020.

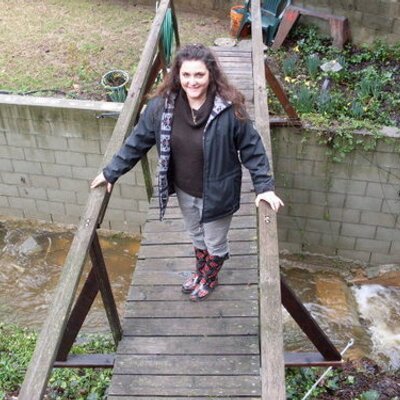

Lauren Frick is an undergraduate student at Indiana University Northwest majoring in English and Spanish. She serves as Student Director of the campus Writing Center, as well as Poetry Review Editor with Great Lakes Review. She contributes regularly to EcoLit Books.