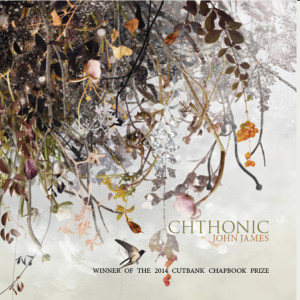

Interview with John James, author of Chthonic

and winner of the 2014 CutBank Chapbook Contest

Interview by CutBank Editor-in Chief Allison Linville, who selected the winning manuscript.

1. First of all, tell us about your book, Chthonic. How would you describe the general premise/theme of the book?

For me, the book was always about digging and waking, and in that process, maturation. By “digging,” I mean, uncovering what’s been hidden, forgotten about, or intentionally buried; “waking,” then, is the speaker’s literal awakening, or realization, of facts or knowledge that should have been obvious to him—we’ll go ahead and say “him”—throughout adolescence. There are a lot of poems about sleeping and dreaming and waking in the book, and that was all somewhat intentional. There’s a lot of talking around things rather than about them.

But this is all very vague. Really, what it’s all about is, my father passed away when I was six years old. The explanation I was given at the time was that he was very sick, and had been for a long time, and that he had died of a disease called “depression.” As a six year-old, I didn’t exactly understand what this meant; as I became a teen, I started putting the pieces together, but since I wasn’t in touch with his family and was, for whatever reason, terribly afraid to talk to my immediate family about it, I remained pretty in the dark about it all. It wasn’t until later, after I’d started working on some of these poems even, that I learned the truth about what happened.

The title attempts to capture that awakening, that un-burial. Since the book came out, I like to joke that I made the mistake of naming it a word that few recognize and almost no one knows how to pronounce. “Chthonic” comes from the Greek khthon, meaning “earth,” or more specifically, “in” or “under the earth”—what is buried in it. There’s of course an ecological component to this meaning, and a historical one, if you’re thinking about it anthropologically. It also refers to the deities of the underworld, which offers a sort of tongue-in-cheek reading of the book’s otherwise heavy subject matter. In a Jungian sense, though, the title refers to the psychological uncovering of, if not repressed memories, ones that have been misunderstood or misremembered, and therefore misrepresented to the speaker (and, therefore, to the reader).

2. How did you start on this manuscript?

I began it as an undergraduate, then again as a graduate student, working on my M.F.A. Needless to say, none of the undergraduate poems survived. I actually sent out a manuscript just after college, which was accepted about a year later (yes, that’s how long the publisher took to get back to me), at which point I felt I had outgrown most of the poems. I actually declined the offer for publication, which seems totally anathema in the writing world, but I’m glad I did it. Those poems weren’t ready to be out in the world.

Maybe half the poems in the book are from my M.F.A. thesis. That original manuscript was called Years I’ve Slept Right Through, which is also the title of the very last poem in Chthonic. I actually sent that manuscript out the year before CutBank selected Chthonic for publication—no bites. But then I was writing these strange, highly emotive poems on the side—I’m referring primarily to the “Schadenfreude” series. I thought those poems belonged in a different book, but somehow when I shoved them all together and found the right title, everything clicked. The chapbook won CutBank’s contest, obviously, but was also a finalist and semi-finalist for a few other chapbook contests. I couldn’t believe the difference just a few changes had made.

3. Was it after these changes that you saw Chthonic as being complete?

Well, as I mentioned, everything sort of clicked when I paired the fractured, highly emotive poems with the more traditional, narrative ones—“His Angels Especially Amaze the Birds,” “Story with a Shriveled Nipple,” etc. And then, of course, there was the title. But the manuscript really felt ready when I introduced the intaglios—the grotesque images that serve as section breakers in the book. My friend Emily did them; they’re etchings. I had told her years before that she could illustrate my chapbook when it came out. As it turned out, that was the very last thing I needed to fit in.

4. What is your writing process normally like? Do you have a specific workplace, i.e. a woodshop?

I’ve never really had much of a “normal.” I write pretty sporadically and every poem’s process is different. I used to spend all day tinkering with a piece, sometimes writing a few lines, staring at it, turning those lines over, only to delete them an hour later and write something else. It was a very laborious way to write and I became such a perfectionist that often I just couldn’t write at all. I would just stare at a blank page. All of that changed after my daughter was born. For about the first year of her life, I think I only finished two poems: “Languor and Languish” and “1956,” both of which ended up in Chthonic. Besides those, which were mostly flukes, I just hadn’t adapted to the time constraints that having a child places on you, especially when, as a teacher, you’re the parent with the more flexible schedule (meaning, you’re watching the baby more). Eventually I figured out how to write very quickly without concentrating much on revision, at least while I’m drafting. That’s how I’ve been writing for the last year.

Because I’m so sporadic, I don’t really have a specific space. Sometimes it’s my desk on the second floor, but sometimes that’s a kitchen counter where my daughter can’t reach the laptop, or in my office at work, or a wrought iron table outside the library between classes. There’s usually a grade book open, and a stack of papers I really ought to be attending to, but I always prioritize the writing. The grading will get done one way or another. The writing will only happen if I make it happen.

5. I know that you were writing for Tupelo Press’s 30/30 Project. How did that change your writing process? Did you discover anything new from that project?

You know, I say I’ve been writing quickly for the past year, but until this month, I’d still written very little. A poem here or there, when I could churn something out. The 30/30 Project forced me to come to the page. I did it every day, and wrote a poem no matter what. After I signed up, I thought, What am I thinking? There’s no way I can keep up with this. But knowing that I had to produce something, that some of it would be crap, and that people would read it regardless, allowed me to produce. It took away some of the constraints that used to keep me from writing a single line.

I have to say, it was pretty difficult at points. I wrote my favorite poem of the month, one called “April, Andromeda,” in about an hour while my partner was making dinner. I usually take part in those kinds of chores, and felt sort of neglectful for not doing so that night—I can’t thank her enough for putting up with me this past month—but moving so quickly, reaching recklessly for the next line, allowed me to create a poem that was more fluid, more fractured, and much more associative than anything I’d written before. It was pretty exhilarating, really. I spent the rest of the month trying to recreate that poem, and though I never did, I produced some other really interesting poems that I never would have written otherwise.

6. Can you dig into some of your unique stylistic characteristics for us?

That’s a tough one. Early on I would have compared myself to Galway Kinnell or Seamus Heaney. I still love how terse their poems are, how the syllables bunch up into rough spondees. Some of that remains, to be sure, but I’ve become more interested in how to create fragmentation through enjambment and lineation, so my poems tend to scatter themselves all over the page. Space is also super important to me, which goes hand in hand with lineation, but how a poet controls white space on a page does a great deal to determine how a reader experiences that text on an aesthetic level.

I’ve also been super interested in the notion of “hypertext,” a 1965 coinage by the information technologist Ted Nelson referring to the links over, between and beyond multiple texts. It’s an essential function of the Internet; we click the links within a text, which bring us to another text, and yet another, and so forth. How, I began to wonder, could this work within poetry? I’ve yet to create a document that virtually links texts together, but more immediately, the notion has prompted me to excerpt material from other texts and insert them into my own. Sometimes this will consist of many lines pulled from a single text, as with “The Healers” or “1956,” which excerpt and play on text from Che Guevara’s The Motorcycle Diaries and Mao Zedong’s poems, respectively. Other times a single poem will excerpt snippets from many different texts. In either case, the resultant poems become fractured and polyphonic—and, when they take on political subject matter, allow me to subvert the politics or the rhetoric of the original text in interesting, even humorous ways.

Particularly with those poems that pull from various sources, I’m attempting to recreate the ruptures and breakage of technological experience, how things like smart phones, the Internet, and social media disrupt our concentration, introducing near-constant updates and rapid focal shifts—sometimes unwanted—that never would have impinged on quotidian experience even ten or fifteen years ago.

7. Where do you find challenges in your writing? What seems to come more easily to you?

Certain images and phrases come up over and over again. Things like “in the wind” or “in the field”—they become fallbacks for me and I tend to over-rely on them as I’m writing. If I could only get them out of my head, I’d be better off. I also turn pretty readily to natural and pastoral imagery. I certainly think of myself as an ecologically minded poet, but I tend to reject terms like “pastoral” or “bucolic.” They're just not part of what I’m trying to do. But being from Kentucky, and writing about those people and that landscape, it’s very difficult to avoid those labels, or even to avoid introducing those images into my work. It’s always been a little frustrating to me.

8. As you know, CutBank is working hard to promote chapbooks as stepping stone publications for a manuscript. Can you talk a bit about the chapbook as an art form and a publication?

On the one hand, I think of the chapbook—or at least my own chapbook—as a preview of what an upcoming book is going to look like. But that’s not to say that a chapbook isn’t a project in and of itself. I think most importantly, a chapbook should be pretty readily digestible—something that can be read in a sitting, or maybe over the course of a day. I don’t know if you can even say that of my own chapbook. It’s definitely on the long side. But digestibility seems key.

9. Can you tell us a little about what’s next for you?

Two things. The 30/30 Project left me with enough poems to assemble another chapbook manuscript, which I may begin sending around. Right now, its working title is The Problem of Science, but that could change. I wonder if it’s worth it to put out another chapbook, though. At least right now. In either case, I’m making serious headway toward a full-length manuscript. I think I’m pretty close. In fact, after last month, I think I’ve just about finished the last leg of the book. I just need to write maybe four more really strong, fairly short poems. It’s hard to say, for sure. Once it’s there, I’ll know—and all I know right now is that it’s not. Aside from some editing and a few reviews, I plan to take May off from writing, and then got at it hard again for a very private 15/15 this June, after which I hope the book will be ready. I aim to start sending it around in the fall.

Thanks, John. It's been a pleasure speaking with you!

You can purchase Chthonic by clicking here.

John James is the author of Chthonic, winner of the 2014 CutBank Chapbook Award. His work appears or is forthcoming in Boston Review, The Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, Massachusetts Review, Best New Poets 2013, and elsewhere. He holds an M.F.A. in poetry from Columbia University, where he received an Academy of American Poets Prize. This fall he will serve as Graduate Associate to the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

Allison Linville is the Editor-in-Chief of CutBank at the University of Montana in Missoula, Montana. She is a recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize and was a finalist for the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Awards. Allison’s poetry has been published in the Bellingham Review, Cascadia Review, the Lonely Whale Anthology, Cirque Journal, and the Whitefish Review. Her nonfiction has been published in High Country News.