"Making this film—adapting Jim’s novel—has really helped to teach me how to not only cope with losses—including the recent, stupid, loss of Jim—but, more significantly, how to ‘be the crystal cup that shattered even as it rang”—how to embrace the power of those we’ve lost, and use their positive impact on our lives to guide our choices—how honoring, indeed, celebrating—the dead keeps us alive."

~ Alex Smith

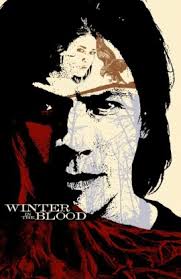

This is an interview between Peter Orner and the people (Andrew Smith, Alex Smith and Ken White) who took on the challenge of adapting James Welch's outstanding first novel, Winter in the Blood, into a feature-length film. It took place by email in April 2001, and was originally published in CutBank 75.

Winter in the Blood, published in 1974, is the first novel by acclaimed author James Welch (1940-2003). A Montana native, Welch attended the University of Montana and studied under Richard Hugo. His work has been awarded an American Book Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, among other honors. He is widely acknowledged as a major voice in the Native American Renaissance.

Winter in the Blood will play on the evening of Friday, October 11 at the Roxy Theater in Missoula, as part of the 2013 Montana Festival of the Book.

PETER ORNER: It must be a daunting challenge to make a film out of book that means so much to so many people. If there are books out there that have achieved a kind of sacred status, this is one. Can you talk about these challenges? How did you decide to go forward with the project?

ANDREW SMITH: It was an incredible challenge at first, until we realized that the novel was also a map—a map that only charts maybe a hundred square miles of prairie, but extends, straight up into the cosmos, straight down into the omphalos, and backwards over 100 years of story and several thousand years of story-telling. I mean, this novel just has so, so much depth—you can lean on it, you know? I think of it as a stanchion—out in central and eastern Montana, ranchers, when they clear rocks off their meadows, pile them in columns, wrapped in chicken wire, to serve as corner-posts to hundreds of miles of barbed wire. I feel like this novel, which Jim said he began as a “travelogue,” has the strength and shadow, of one of those stanchions. Every word a stone cleared from that prairie, each one freighted with history and rebellion. So, yeah, it’s a challenge, and it’s a legend; but it’s also a great honor—like we’re entrusted with carrying something important forward—and every time we get lost, we realize the directions are right there, pointing us home.

ALEX SMITH: Yes. Each new read of Jim’s book reveals more bounty. After a while I stopped highlighting key lines because I found that my entire dog-eared copy of the book was glowing neon orange. Also, one of the hardest things to replicate was how seamlessly the book dances between the present and the past. Wee sentences are tucked into nooks and crannies throughout the book that do epic work.

ANDREW SMITH: Another thing to keep in mind is, no matter what kind of film we make, the book will always be standing there, casting that long, lean shadow. The hardest part was giving ourselves the liberty to make significant changes to the story. The Scottish filmmaker Lynne Ramsey has said that in order to adapt something to the

screen, one must first replicate the source, and then destroy it, and then rebuild it. Destroying is the hard part, because it’s kind of sacrilegious, and you just have to trust that you’re keeping to the authentic spirit of the original work, or what you’re doing will end up profane. But you also don’t want to defile it by being less than courageous. And we can never destroy it, of course, because the novel is totally alive.

KEN WHITE: Well said, Andrew. You have to have the courage to hold your heart open and let the novel pour into it, but first you have to give yourself permission to change and to be changed. Beyond getting our minds around what initially felt like an act of transgression, many of the destructions and rebirths that happen during the adaptation process are largely a concern of form—there’s simply not enough ink-space in a script to hold that whole world in language—so you have to get Brancusi on it and rely on the integrity of the characters’ shapes within the story.

When we're creating elements of the script which were not in the novel, the test was to hold them up against a ‘Welch-world’ template. Among the three of us we basically developed a sense of how far and deep the parameters of poetry and absurdity extended in the novel and whether our inventions were working in concert with that universe or against it.

ALEX SMITH: Our biggest goal was to be true to the emotional heart of the story—we knew we could play fast and loose with plotting and dialogue as long as there was a veracity of feeling. As far as ‘sacred’ goes, we fortunately had the great luck to know Jim Welch, and to know him well—well enough to know that he was always a bit skeptical about ‘the sacred’, that he always leavened any loftiness with a profane counterpunch, whether it be the horse named Bird farting or Lame Bull’s jumping on Grandmother’s coffin to make it fit too short a hole in the ground. That knowledge allowed us to move beyond reverence.

ORNER: I think of those haunting opening lines of the poem that begins the book. “Bones should never tell a story / to a bad beginner.” I’ve always wondered about those lines. Seems to me we’re all, one way or another, bad beginner—and that we’re not always worthy of the stories that are bestowed upon us by our grandparents, by luck, etc. And yet the book seems to say, do the best you can. You may not be worthy but who else do the bones have to talk to? Any thoughts on this? How will the film capture this spirit?

ALEX SMITH: Indeed, that line,“Bones should never tell a story,” was so intriguing, so right to us that we put it in the script—spoken by the Grandmother to our hero when he was a kid. I remember, years ago, Jim telling us that he believed that most writers were, basically, the children who listened to the stories told by their grandparents. Beginners are, by definition, bad, and it’s very hard for them to read the stories imprinted on the bones. But that’s okay—it’s supposed to take time to understand. The stories have been talking to our main character for a long time, but it is only now—during the four-day journey of the story—that he is trul

y beginning to listen—and beginning to be, as you say, worthy.

ANDREW SMITH: Right. You know, Jim doesn’t name the narrator/hero in the novel, because he says he hadn’t earned a name until the last pages of the story. We’ve called our hero “Virgil,” but you’ll never hear another character in the film call him by his name: he hasn’t earned it yet.

ORNER: A related thought: Louise Erdrich says emphatically that Winter in the Blood is not a bleak book, that it is above all about the stories we tell and the memories we remember and misremember. Do you agree?

ANDREW SMITH: I agree emphatically. The novel is made up of inscribed, hidden, forgotten, and if-only-they-could-be-forgotten memories and stories. Our hero travels as much in his mind as he does on his feet or with his thumb, probably more. And I think at the heart of it is Pound’s poetic edict, “What thou lovest well, remains…”—for though most of the inscribed stories are stories of loss, their telling creates a continuance of life. And, of course, the narrator’s discovery of his own bloodline is also a discovery of a secret, silent, enduring love. And to make a story your own is necessarily to misremember it—the narrator, for instance, in recounting the death of Mose, says, “it was dusk, when the light plays tricks on you…” and he blames himself all these years, even though he was a 12-year-old boy trying to do a man’s job when the accident happened. His ability to forgive himself is part of his maturation process. He’s looked despair in the eye, and stared it down.

I’ve read in interviews with Jim that he was surprised that people found the novel bleak because he thought it was just as funny as it was hard. I find it funnier every time I read it, and I’m excited to try to capture that humor on the screen. I think maybe Jim wrote his second novel, The Death of Jim Loney, to show people what a bleak novel could feel like. But you know, that’s funny, too.

ORNER: The book is as much about memory as it is about the present action of the story. It’s a complicated narrative structure. How does your screenplay address these complications concerning the nature of memory and time?

WHITE: One of the things that helped inform our approach to the fluidity of the experience of time and reality in the script was The Death of Jim Loney. Loney often experiences time as a sort of elision. Sometimes Loney-time is even stacked like playing cards translucent except for the ink of their suits—just hearts and spades from many times suspended in a single space. I remember we had a real breakthrough in terms of transitional elements to let time shift, stretch, and elide in the script for Winter in the Blood when we learned from Loney (from Jim Welch, really) how to relax and let time be its simultaneous and Silly-Putty self.

ALEX SMITH: The best way we could figure out how to cinematically capture the novel’s seamless ‘drift’ between the now and the then, was to come up with a visual device that, during many of our flashbacks, actually places the grown-up Virgil in his past—i.e., he will often, literally, share the same frame with his younger self. As Faulkner put it, “memory believes before knowing remembers”, or as Jim puts it, “the memory was more real than the event itself, you know?” Every memory we have, we have in the present tense—it’s not happening then, it’s re-happening now. So the trick is to make then now—and the best way to do that on film is to make the past visible, both in Virgil and around him, and, conversely, to make the adult Virgil a visual presence in his own past. Yeah?

ANDREW SMITH: Yeah.

WHITE: Isn’t that what I said?

ORNER: You all have an intense personal relationship to James Welch and this story. Would you mind speaking a bit about what this project means to you all on a personal level?

WHITE: Alright. Straight skinny. For me, and I don’t think that I’m flying solo on this, the entire project, starting from a middle-of-the-night January dream at the Smith ranch to becoming what is now a front-and-center-all-demanding reality in pre-production has been a profound sort of personal evolution in terms of my relationship to art, collaboration, and as it turns out, community—which I’m coming to understand might be the whole point of art. Or even existence—hell if I know, but it seems likely.

I do know that my former Dickenson-kept-her-work-in-a-trunk kind of relationship to art as private artifact written with a quill dipped in berry juice on magician’s parchment and foxed inside some elm-cranny had its elm pulled out by the roots. As it turns out, in order to really, really bloom in terms of relationship to the novel, the script, the project, Andrew & Alex at each new step of collaboration, each new partner in the production process—all that Winter in the Blood required was total surrender, that’s all. No biggie, right? All I had to do was give over to it entirely, and it opened a door in every wall. In the film’s blog I tried to approach the experience as being part of an ever-growing braid but feeling the strands of the past and the future just as presently as those of the present. This isn’t quite right, of course, these descriptions. I suppose that most directly, the more I gave over to the project, the more connected—the more fused I felt to everything. The art worked on my life—that was the spell. The novel is a 176-page spell you sing aloud to change the weather.

ALEX SMITH: At the end of Winter in the Blood, the nameless narrator talks about how his dead older brother was “good to be with” even on a rainy day. That’s how I think of Jim. From the age of six on, I always looked forward to seeing Jim, no matter what. He was such a great storyteller because he was so interested in hearing everyone’s stories. Because Andrew and I grew up surrounded by scads of hard-drinking writers, there were always a lot of huge personalities around, and it was hard to get a word in edgewise, but Jim would often find a way to involve us in the conversation—and that meant a lot to me. He gave voice to the voiceless.

ANDREW SMITH: That comes up again and again—Erdrich, Sherman Alexie, our young actress, Lily Gladstone, even the African-American poet C.S. Giscome, and many others—they all talk about how they were given “certain permissions” to speak via reading Jim’s novels.

ALEX SMITH: Jim was always genuinely curious about everyone’s life—which was why he was able to soak up so much, and put so much behavior in his stories. He was a great model. Also, because Andrew and I lost our father so early, I always had a bit of a ‘paternal’ sonar going—I was always looking for male ‘blips’ that signaled ‘kind’, ‘open’, ‘sincere’, ‘genuine’—and Jim was goliath on that screen.

So, to me, there is a very personal component to this film. Not only does making it keep me in touch with him—it’s really allowed me to understand him—to know him—in an entirely new way. Making this film—adapting Jim’s novel—has really helped to teach me how to not only cope with losses—including the recent, stupid, loss of Jim—but, more significantly, how to ‘be the crystal cup that shattered even as it rang”—how to embrace the power of those we’ve lost, and use their positive impact on our lives to guide our choices—how honoring, indeed, celebrating—the dead keeps us alive.

ANDREW SMITH: Well put. And honoring the dead is what the film/novel is about—about making peace with their loss, or as Virgil discovers—no longer being “a servant to the memory of death.” Freeing oneself from that obligation; a much more kinetic place in which to exist. It’s not such a burden to carry once you realize you’ll never really lose it. “Possessions can be sorrowful,” as Yellow Calf says.

WHITE: Yup. A good ending for a bunch of bad beginners.

ORNER: So many vivid characters in this novel, from the narrator to Lame Bull, First Raise, Yellow Knife, Airplane Man. I’ve saved my favorite character for last: Teresa. I find her remarkable in many many ways. I particularly love the scene where she and the narrator remember what happened to the duck Amos. Can you discuss the challenges to bringing these incredibly unique people to life on the screen?

WHITE: Each character is incredibly unique—but that’s Welch, so the challenge was in being true to what was already there and learning from it. Even very minor characters—like shorthand—are essential. The greater challenges were in deciding what/whom to leave out and what to invent. Teresa is remarkable—she’s one of my favorites too. She needs her own movie. And she’s complicated; she’s both consistent and mysterious. She is the linchpin holding together the ranch and what elements of family remain, but has many inner rooms reserved only for herself. Because she chooses to actively engage the responsibilities of just being, so much of every burden is mostly on straight-backed unsung Teresa. She’s the one who makes difficult decisions and stands by them.

Teresa is also the most reliable conduit of memory and seems to resist the impulse to mythologize the past better than other characters. In the scene you reference—the one that begins with Teresa and the narrator talking about Amos the lone surviving duck and moves to the memories they each have about the death of First Raise—the narrator admits this. For him, “Memory fails.”

Teresa seems to have a pretty clear grip on memory and it’s not nearly as neatly packaged as it is for some of the other characters. Maybe she wishes it would fail. In the same scene, Teresa’s pragmatism is summed beautifully by one delicate, deliberate action—Jim seems to do this effortlessly—in the same scene. This is one of those epics contained in a gem tucked in the nooks and crannies that Alex references. As one of the few people who questions Virgil directly, Teresa asks him some difficult questions. Mid-conversation, Teresa notices a dandelion parachute clinging to the rim of her salad bowl. She asks another no-bullshit question, then blows the parachute away. The scene ends with her recommendation that the narrator look around for other work—there’s no longer enough for him at home. Teresa’s always doing that—blowing the narrator’s parachutes away.

ALEX SMITH: Alas, we don’t have the Amos the Duck scene in our film. We love it, but actually filming drowned ducklings ultimately felt too—easy/maudlin. The scene does do a lot of heavy lifting in the book—beautifully illustrating the ‘neglect’ and ‘rural tragedy’’ Virgil constantly had to face—but we couldn’t find a home for it on screen.

ANDREW SMITH: Maybe in The Production revision. Maybe some ducks will just show up that day and insurrect their way into the film.

ALEX SMITH: Stranger things have happened. But we did know we needed a scene, somewhere, where Virgil and Teresa actually confront the elephant on the ranch—the death of Mose, and who was to blame, and how raw the wound still is 20 years later. And it was, wonderfully, the giant wheel of this project that lead us to a solution—real life informing Jim’s novel; Jim’s novel influencing, of course, our script; our script leading us to scout the Hi-Line and the Fort Belknap Reservation; the Reservation leading us to an actual family gravesite; the gravesite leading us to a weathered saddle hanging on a lodge pole rail; the saddle giving us the perfect visual metaphor for the ghost of Mose, our dead “Indian cowboy." In other words, it took us inhabiting the novel’s ‘truest’ character—the actual landscape— for us to really understand, write, and cast, (and soon direct) the characters inhabiting it.

ANDREW SMITH: Yep. As Jim put it—“Dirt is where the dreams must end.”

________________________

Peter Orner is the author of the novel The Second Coming of Mavala Shikongo, the short story collection Esther Stories and the forthcoming novel Love and Shame and Love. He co-edited Hope: Deferred: Narratives of Zimbabwean Lives and edited Underground America: Narratives of Undocumented Lives, both collections of oral histories published by McSweeney’s Voice of Witness Series.

Andrew Smith is a filmmaker, poet, screenwriter and associate professor in the School of Media Arts at the University of Montana. He and his twin brother, Alex Smith, a prize-winning filmmaker, screenwriter, educator and author, wrote and directed the critically acclaimed feature film The Slaughter Rule. Andrew and Alex, together with poet, actor and screenwriter Ken White, adapted James Welch’s beloved novel, Winter in the Blood, to film, which was shot in July/August 2011 on location at the Fort Belknap Reservation and surrounding Hi-Line towns.

CUTBANK: What are you doing for the conference?

CUTBANK: What are you doing for the conference?

RM: How did this project emerge, as in these thirteen poems together via Slash Pine Press?

RM: How did this project emerge, as in these thirteen poems together via Slash Pine Press?

We caught up with Dennis James Sweeney, winner of CutBank’s 2013 Chapbook Contest, to get some insight into the poetics and process of his poetry collection, What They Took Away. Lily Hoang calls it “an epic apocalypse of life stripped of tedium, of obtrusiveness” and a “magical miniature world showcas[ing] the terror of erasure and the wreckage of return.”

We caught up with Dennis James Sweeney, winner of CutBank’s 2013 Chapbook Contest, to get some insight into the poetics and process of his poetry collection, What They Took Away. Lily Hoang calls it “an epic apocalypse of life stripped of tedium, of obtrusiveness” and a “magical miniature world showcas[ing] the terror of erasure and the wreckage of return.”

Interviewed by Allison Linville

Interviewed by Allison Linville Aryn Kyle: I feel like I need to start off by telling you that as I am writing the answers for this interview, I currently have $9.62 in my bank account (to be clear: the decimal point is not misplaced—nine dollars, sixty-two cents). I’m not offering this as evidence against my being “the dream MFA success story,” but as an attempt to give you a more holistic view of the reality.

Aryn Kyle: I feel like I need to start off by telling you that as I am writing the answers for this interview, I currently have $9.62 in my bank account (to be clear: the decimal point is not misplaced—nine dollars, sixty-two cents). I’m not offering this as evidence against my being “the dream MFA success story,” but as an attempt to give you a more holistic view of the reality.